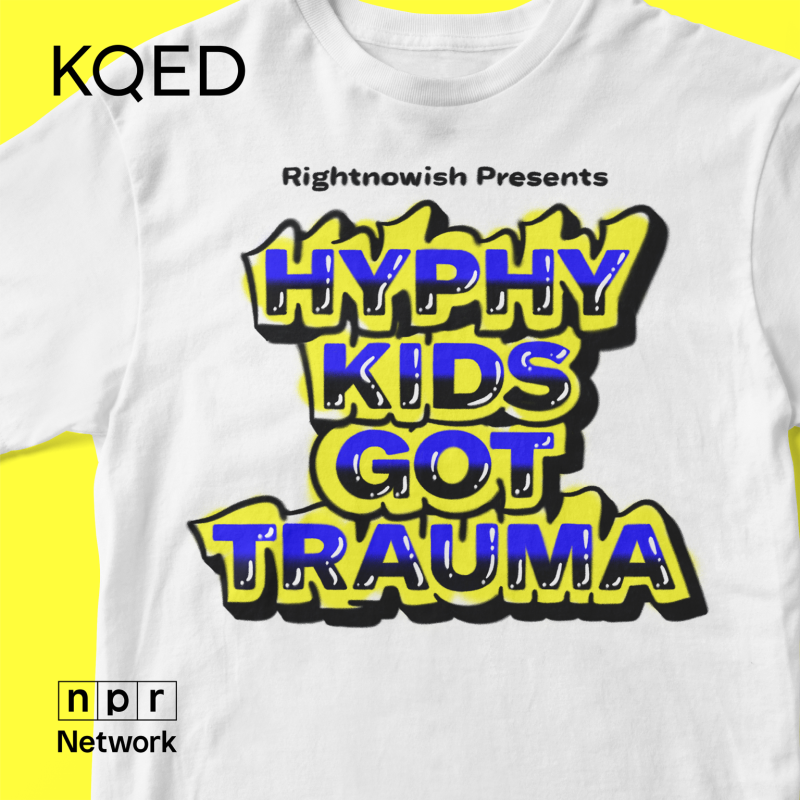

Ericka Cruz Guevarra: Yeah. I’ve never thought of the words hyphy and trauma in the same sentence, but Pen would know. He was a budding journalist with a front row seat to the movement in 2006. And today, we talk with him about the sounds and scars of the time and explore the hyphy movement as you’ve never heard before. Stay with us.

Ericka Cruz Guevarra: Pen, this series of yours, Hyphy Kids Got Trauma takes place in 2006, the height of the hyphy movement. Can I tell you where I was in 2006 and during the hyphy movement?

Pendarvis Harshaw: Please bring me into your world.

Ericka Cruz Guevarra: So I was, I’m going to date myself, 11 years old, going to middle school in Sassoon City, California. I was on MySpace even though my parents didn’t want me to have a MySpace. Definitely had a pair of stunner shades. I would say I probably was experiencing the hyphy movement really on the radio and online, like on the drives that my family would take every week to Vallejo to go visit our family out there. Be Wild 94 nine. When I was at Cameo Camille listening to the hyphy music in that way, and then on people’s MySpace pages. So that’s where I was.

Pendarvis Harshaw: This is made for you. This is made for the kid who who was there but wasn’t fully there but can reminisce. It’s touch points.

Ericka Cruz Guevarra: Well, I feel like I was experiencing the hive movement. I’d say like from the back seat. You had a front row seat to this time in Bay Area hip hop history. Can you explain where you were in all of this?

Pendarvis Harshaw: Yeah. Talk about seats. I got my first car from an auction like the Alameda County Police auction in Livermore. This bucket, Chrysler that I got with my student aid check from Laney College. And that’s how we got around. I was 18, going on 19. Just graduated high school. I had applied and had been accepted to Howard University in D.C. and I knew I wanted to do journalism. So I had this camera and I went everywhere I went. I just filmed it and we would hit everything from community events to parties to sideshows. And that living on the edge, I think, really is what kept us going. We knew it was dangerous, but it was enticingly dangerous, and that’s what made it fun. And that’s where we found freedom. And that’s largely what this piece is about.

Ericka Cruz Guevarra: Well, that’s like, amazing to think about. You were a baby journalist. You were a college student living in Oakland at the center of this, I think, very youth driven movement. And you were a witness to this, like very exuberant time. But this series alludes to something more that was happening there, this idea that have kids got trauma. What do you think people often misunderstand about the hyphy movement?

Pendarvis Harshaw: The term hyphy itself comes from a hyper active person. I often heard it when somebody is describing a dog off the leash, like, Oh, that’s the hyphy pitbull means stay away from that. So the term just starting new and how it’s used and applied to folks, you know, it was already off a little bit. When people think of hyphy, especially like on the national scene. So keep in mind, in 2006 I leave Oakland and go to Washington, D.C. for college, and I start to see how people view the Bay Area from the outside. And I’m like, Oh, you. I think it’s all fun and games I think is goofy. Like, no, this hyperactive energy actually comes from really a void. A lot of us born with parents who were addicted to drugs and that that hyperactive energy often turned malicious. And I don’t think it was depicted that way once it hit, the national media hyphy became a little little more friendly, a lot goofier and easier to digest.

Ericka Cruz Guevarra: You were just alluding to this pen, but what else was happening in Oakland in 2006? What is the context of the hyphy movement during this time?

Pendarvis Harshaw: So as E-40 might get a report card album which features the song Tell Me When to Go and to? Blow the Whistle. Album and song start to blow up and people are dancing and partying at the same time. Oakland is witnessing an uptick in homicides where that year 2006, 148 people were reportedly killed in the city of Oakland. In January of that year. I lost a friend by the name of Willie Clay in November of that year. I lost a friend by the name of Marcel Campbell. And in between, I just remember so many R.I.P. memorials and people with airbrushed T-shirts that say R.I.P. on them and pamphlets from funerals in the dashboard of a Buick lightsabers at the Sideshow. So people are partying while still mourning.

Pendarvis Harshaw: Now that I have the language to express, oh, that’s what we were going through. We were processing this trauma. And so as I start to kind of pull back the layers of what was happening, it’s not just the 114 homicides. It’s also the amount of unemployment. It was the fact that you have predatory housing loans, overpolicing. Oakland Police Department went into federal receivership in 2003. And so this podcast, it starts off with, yeah, talking about going down and shaking your dress. But yet slowly but surely, they start to keep pulling back these layers and see why these hyphy kids are so hyphy.

Ericka Cruz Guevarra: Episode one starts with a very personal experience of yours. The moment that you found out that a friend of yours named Willie Clay, who was an old middle school classmate, used to play ball with ride razor scooters with, was actually killed. Why did you start the series there Pen?

Pendarvis Harshaw: Willie Clay was one of the first close friends that I lost to gun violence over the past two decades. When I think about how many people I know who have been killed, I think back to Willie Clay story. So I wanted to start there because it had that lasting impact on me as an 18 year old kind of stepping out into the world. It also happened in January of a very monumental year. So I thought that was the best place to start, especially from when to tell my story in the context of what was happening around me.

Ericka Cruz Guevarra: Well, the series dives into the ways that that kind of violence that people were experiencing in Oakland directly led to this new wave of talent. Can you talk about how that happened?

Pendarvis Harshaw: While I’m on one side of the neighborhood mourning for the loss of Willie Clay, on the other side of the community, there’s a brother by the name of Beeda Weeda, who’s an artist whose music is on the rise.

*music clip*

Pendarvis Harshaw: You know, after a number of incidents in the community beat, his management suggested that he record instead of in the neighborhood known as the Dubs and East Oakland. He recorded the high road building, which is a building owned by the legendary all mighty Hieroglyphics. Hip hop crew idolize the wind a little bit. It started recording at the Hero building and when he got in, essentially kicked in the door for a whole bunch of new talent from the Bay Area. I’m specifically from Oakland, an artist who still make music to this day. Everyone from your Jay Starling. Thank you. Hey, let him preserve this track. Nick it don’t call me. I’m sorry. Beck Shady. Nate. Hey. How was that? Go through the ghetto to say through the halls. Get the clapping that you niggas like around. Pull out. I’m bringing back Filthy Rich from seminary who’s doing magnificent things in my piece. Stand up in this front line. When I’m in, I’m straight. Oh, jeez. From my hood. That kind of story. Beyond just music. These are people who created businesses and sustain their families. And yet, like, music is one thing, but to create real generational change. That’s what happened there.

Ericka Cruz Guevarra: And I know one thing that pushed beat Twitter to the hero building was the gun violence in his community and gun violence that had hit him personally. And I know you talked to Taj Massey of the Souls of Mischief, really, about how that trauma is manifested in bittersweet as music itself. Right. Can you talk about how Taj described the sound of Bittersweet as music when he first heard it.

Pendarvis Harshaw: Beeda’s music? He has this one song called We Ain’t Listening.

*music clip*

Pendarvis Harshaw: When Tajai talks about it, he talks about it like it’s almost demonic. You know, the way that people describe hip hop, like in the negative way. Like, oh, what are these kids doing? That’s devil music. That’s really what hip hop is in general. Rapping, Like we just rapping, you know. And so to me, it exemplified the same feeling that maybe, you know, raising Hell or Rock Box or something. That. Dude. No, no, no, no. You know, or it’s like a jungle sometimes. Like it exemplified that spirit of there’s a whole other world out here that you are not being exposed to, and we’re going to make it sound beautiful over music.

Pendarvis Harshaw: And when I heard that at 18, it spoke to me. It wasn’t like, I’m going to miss you. It’s like, Oh, I miss my friends. Or what’s happening with society, What’s going on? It wasn’t Marvin Gaye or anything like that. It was like aggressive. It was something to roll my windows down to like smoke and drive and like, really provided a vent for me, my friends and my community. I was nervous to ask people about trauma and how they express it, and a lot of folks were like, Yeah, man, we express it by like smiles and like laughter and like, partying aggressively.

Ericka Cruz Guevarra: And that idea is also represented in this viral video that you shot of Stomper, the Oakland A’s mascot in the early days of YouTube, which, by the way, I literally saw someone the other day post that video on Instagram, and I just wanted to be like, Do you know who took that video? I know the person who took his hand.

*video clip*

Ericka Cruz Guevarra: Can you tell me about that video that you shot and and the role that it played in in this episode for you and in sort of being a real, I think, visual representation as well of this idea that trauma is very much represented and can be seen in the culture of the hyphy movement.

Pendarvis Harshaw: Episode two starts with me showing a video of Stomper, the Oakland A’s mascot, dancing at a E-40 record release party in Emeryville in 2006. Crazy. Oh. Stompers, a goofy gig and having fun. The people around him are having fun. Hugs and smiles. And then I watched it again. I was like, Wait, what song is playing in the background? It’s E-40 happy to be here, in which he’s talking essentially about surviving hard times and losing loved ones along the way. And then I’m watching the video even closely. And I mean, it’s, you know, it’s pixelated. It’s 26, right? But I can see that one of the people has a airbrushed t shirt on and it says R.I.P. across his chest as he’s dancing and gig and having fun.

Pendarvis Harshaw: I’m like, those are signs of what we were experiencing at that time. I don’t think we knew at the time that we were like expressing pain, but surf dancing or being just doing hip hop. I feel like that was just something we did. And again, in retrospect of looking at it like, Oh, the biggest turf dance video that is on the Internet right now is turfing in the rain, where a group of young men are on a corner in East Oakland honoring their deceased loved one. Like that speaks volumes of the culture of turf dancing.

Ericka Cruz Guevarra: Well, speaking of YouTube, as we were just talking about, there are four total episodes of Have Kids Got Trauma. And I know the third focuses on kind of like the concurrent rise of social media during that time. You know, I think back on my experience, MySpace and YouTube really allowed, I think people like me from the suburbs to hear and see the music and the culture without being in the thick of it. Right. Like sort of experiencing it, but seeing it removed from the context to become this thing that really you just experience online. Once social media kind of did start to influence the movement. Penn What effect did you see it having on the sort of. Story that we know about the hyphy movement or that we think we know about the hyphy movement.

Pendarvis Harshaw: It was a combination of both social media and also major media outlets, shifting the narrative, taking the story and packaging it and selling it as they want to. Social media brought about a lot of copycat stuff. So I think I’ve talked to people about seeing Ghost riding the whip on video and then how they try to reenact it wherever they were. Now, how many times are videos posted of people go through the whip going wrong culture, It spreads, and when it spreads, people are going to take aspects of it and incorporate it into their lives and things are going to change and that is just natural. And then the unnatural side of things is when companies, big publications, record labels, they try to take something that’s a phenomenon, a youth phenomenon, and package it and send it back to the youth. And that’s one of the things that I saw. We saw it happen in hip hop in general and then specifically in the hyphy movement.

Ericka Cruz Guevarra: I have to imagine that it was difficult and probably painful to revisit some of this time in this particular way. But why was it important for you to look back at this time through this lens? Like, what do you hope I guess to remember by doing this.

Pendarvis Harshaw: Before the podcast came out, I had the opportunity to share some of the things that I was working on with a group of people at the Academy of Sciences, and we talked about this area. That open discussion allowed me to see the benefit of telling the story is that people see that they’re not alone. A lot of folks shared with me personal trauma that they really hadn’t thought about from 2006 or even prior. And so this podcast project is an opportunity for the community to come together and say, you know what, collectively we did go do something at the start of the millennium and what can we learn now so that we don’t pass that trauma down to the next generation?

Pendarvis Harshaw: At the end of this project, just last week, I saw a kid I look at as a nephew speaking to Boots Riley at Fremont High School, and he was talking about the beauty of the hyphy movement and how it brought people together. My kids were born in 2006, and so he looks at it, you know, kind of like fondly. And also it’s awesome that he has that perspective on the hyphy movement because obviously his dad did something right to ensure that it didn’t get passed down to him. Whatever traumas his father experienced then didn’t get passed on him. That’s what I really wanted to do, is acknowledge what we went through and be clear about the causes of them and see see it so that we don’t pass them down to the next generation.

Ericka Cruz Guevarra: What do you tell your daughter now about the hyphy movement and how do you think about this idea of like not passing your that trauma down to her?

Pendarvis Harshaw: Getting a little ahead of myself, but my next project or next piece, a next podcast that I’m working on is about parenthood and music, how music is a teaching tool. And I realize I don’t talk much about the hyphy movement with her. I mean, she’s seven and there’s a lot of vulgarity in the hyphy music. And so, like, maybe, maybe that’s the reason, like we’ve, we’ve listened to globally. That’s all we listen to too. Sure. Like, oh, too short, like, you know, getting it or, you know, like kind of uplifting to short.

Ericka Cruz Guevarra: You no blow the whistle for her.

Pendarvis Harshaw: Yeah. Not. Not yet. Not yet. I’ll wait til she comes home from school and she’s talking about. I’m like, What? You know about It’s time to teach you. We haven’t gotten to that point, but when we when we do, I definitely want to be able to provide context and full context and say it’s not just about going down. It’s it’s deeper than just shaking your dreads.

Ericka Cruz Guevarra: Well Pen, thank you so much for this series and thank you for chatting with me. I appreciate it.

Pendarvis Harshaw: Always a pleasure. Thank you. Thank you. Thank you.