A former agricultural city, Lathrop has a population that’s grown 11% in the past year (PDF) as workers priced out of the Bay Area flocked to the area for its relatively affordable housing. But as they do, those workers commute farther into the cities for their jobs.

The Bay Area now has the largest share of super commuters nationwide, commuters who spend more than 90 minutes traveling to work or back each day, according to an Apartment List study. Transportation now accounts for nearly half of the state’s carbon emissions.

California’s housing and climate officials hope to combat these emissions by encouraging — or, in some cases, forcing — cities to allow more apartment buildings to be built near train stations and along major bus routes. In San José, a Silicon Valley city with sprawling single-family neighborhoods and highways that run through the middle, housing advocates and urban planners are trying to redesign its suburban streets into compact, walkable neighborhoods.

“At the end of the day, it’s really a geometry problem,” said Matthew Lewis, the communications director for the housing advocacy group California YIMBY. “The amount of land you have in a city is finite, and if you use all of it for single-unit homes, you’re going to quickly run out of land to house the people who want to live there.”

But the shift from suburban to urban hasn’t been easy, partially because many of the city’s policies favor sprawl and work against the changes planners want to see. Some argue the city’s proposals are too ambitious and its development requirements are overly bureaucratic for apartments and commercial spaces to be built quickly and within budget. Housing advocates are pushing for gentler options, like adding smaller homes to existing single-family lots.

As San José tries to dramatically reduce its carbon emissions and build more housing simultaneously, the lessons it learns are relevant nationwide as other cities seek to do the same.

The urban village plan

More than a decade ago, officials in San José adopted a plan to transform underused lots near train stations into thriving neighborhoods called “urban villages.” State officials say this kind of development is the way forward for California to meet its ambitious housing and climate goals to add 2.5 million new homes to the housing stock and to cut its carbon emissions in half by 2030.

“Given the persistent housing crisis California faces, we know that we’re not going to build our way out of that crisis by building single-family homes,” said Sam Assefa, director of the Governor’s Office for Planning and Research. “More compact, transit-oriented development is the sensible way to do it.”

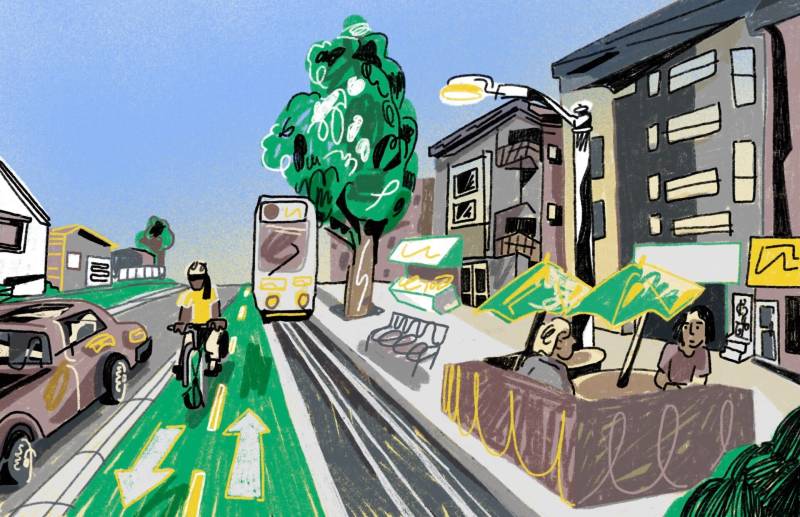

San José’s urban village plan wants to transform underused lots into vibrant, urban neighborhoods. In this artist’s rendition of what the Berryessa BART Urban Village could look like, the Berryessa Flea Market would be replaced with more housing, outdoor parks and room for cyclists and pedestrians.

In 2011, the city council envisioned 60 of these urban villages spread across the city — tall apartment buildings with stores and restaurants on the ground floor, all built near train stations or along major bus routes. Two years after the city passed the plan, it partnered with local climate advocacy group The Greenbelt Alliance to release a video championing the idea.

“They promote community, the opportunity to enjoy an outdoor cafe in a public space, meet new people, engage in new conversations, and ultimately build relationships in the community,” former mayor Sam Liccardo said in the video.

One of the most highly anticipated urban villages to be built would surround the city’s first BART station once completed. Note: this illustration is an artist’s rendition of what the development could look like once completed, but the design could change once a developer takes over the project.

But the 12-year-old plan has been slow to come to fruition. So far, only 12 of the 60 villages have been approved, and only a handful of those have been completed. According to a 2019 report from the housing advocacy group SPUR, developers have admitted to actively avoiding urban village projects (PDF) due to their cost and the complicated approval process.

“This kind of dense housing is more expensive to build, and the biggest barrier right now — not just for urban villages, but for anything — is the cost of construction,” said Michael Brilliot, deputy director of citywide planning for San José. “Cost of construction continues to go up year after year. Interest rates have gone up, so these projects no longer pencil out [for developers].”

The Berryessa BART Urban Village, one of the most highly anticipated pieces of this plan, illustrates the many problems developers and city planners are running up against when trying to bring this urban village vision to life. Situated adjacent to the city’s first BART station, which opened in 2020, the development is expected to add more than a thousand new homes and acres of retail space to the area.

Developers have built a 551-unit apartment complex with retail and restaurant space on the ground floor. But two years after the complex opened, the commercial space is mostly vacant, driven by lower demand for retail space since the pandemic.

“I hope to see more people, more entertainment areas, stores — I would hope to see that soon,” said Juan Carlos Navarro, who has lived in this neighborhood for the past two decades. “This [block] was all empty before [the apartments were built].”

But, advocates for pedestrian-friendly design argue that the urban village is still too focused on cars. A large parking lot serving a strip mall with a Safeway, a Dunkin Donuts and a CVS next door to the apartment complex is rarely full, and the apartments’ residents have to cross a busy, four-lane thoroughfare to get there.

“I think there’s a lot to re-imagine here in terms of reusing some of the car lanes into places that can better serve people,” said Erika Pinto from the housing advocacy group SPUR. “Imagine if the bike lane was better protected so that bicyclists felt safer moving around. Imagine if the sidewalk was increased to allow people to walk by, for vendors to set up shop.”

The city’s policies, which have historically favored single-family housing and office space, restrict where tall apartments can be built and, in some ways, counteract efforts to make the neighborhood less suburban.