AB 873 passed nearly unanimously in the Legislature, underscoring the nonpartisan nature of the topic. Nationwide, Texas, New Jersey and Delaware have also passed strong media literacy laws, and more than a dozen other states are moving in that direction, according to Media Literacy Now (PDF), a nonprofit research organization that advocates for media literacy in K-12 schools.

Still, California’s law falls short of Media Literacy Now’s recommendations. California’s approach doesn’t include funding to train teachers, an advisory committee, input from librarians, surveys or a way to monitor the law’s effectiveness.

Keeping the bill simple, though, was a way to help ensure its passage, Berman said. Those features can be implemented later, and he felt it was urgent to pass the law quickly so students can start receiving media literacy education as soon as possible. The law goes into effect on Jan. 1, 2024, as the state begins updating its curriculum frameworks, although teachers are now encouraged to teach media literacy.

Berman’s law builds on a previous effort in California to bring media literacy to K-12 classrooms. In 2018, Senate Bill 830 required the California Department of Education to provide media literacy resources — lesson plans, project ideas and background — to the state’s K-12 teachers. But it didn’t make media literacy mandatory.

The new law also overlaps somewhat with California’s effort to bring computer science education to all students. The state hopes to expand computer science, which can include aspects of media literacy, to all students and possibly even require it to graduate from high school. Newsom recently signed Assembly Bill 1251, which creates a commission to look at ways to recruit more computer science teachers to California classrooms. Berman also sponsors Assembly Bill 1054, which requires high schools to offer computer science classes. That bill is currently stalled in the Senate.

Understanding media and creating it

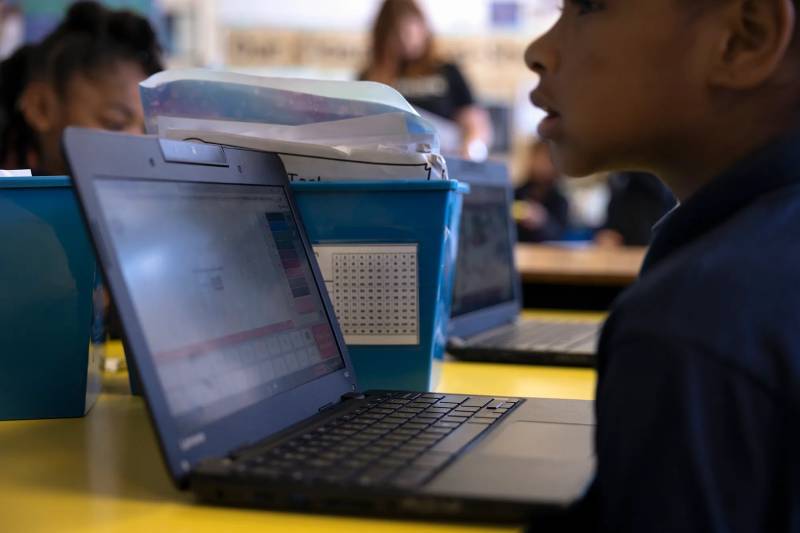

Teachers don’t need a state law to show students how to be smart media consumers, and some have been doing it for years. Merek Chang, a high school science teacher at Hacienda La Puente Unified in the City of Industry east of Los Angeles, said the pandemic was a wake-up call for him.

During remote learning, he gave students two articles on the origins of the coronavirus. One was an opinion piece from the New York Post, a tabloid, and the other was from a scientific journal. He asked students which they thought was accurate. More than 90% chose the Post piece.

“It made me realize that we need to focus on the skills to understand content as much as we focus on the content itself,” Chang said.