View the full episode transcript.

Last year, Oakland returned 5 acres of Joaquin Miller Park to the Sogorea Te’ land trust and the Confederated Villages of Lisjan, marking the first time a Bay Area city has given land back to Native Americans.

Despite no significant opposition to this plan, the process took more than 5 years. So what does it actually take to give land back?

This episode originally aired on Nov. 28, 2022.

Episode Transcript

This is a computer-generated transcript. While our team has reviewed it, there may be errors.

Alan Montecillo: Hi, I’m Alan Montecillo, in for Ericka Cruz Guevarra. And welcome to the bay. Local news to keep you rooted. Last year, Oakland did something that no other city in the Bay Area had done before; returned land to indigenous people.

Corrina Gould: It’s a place that we imagine not just engaging the tribe but everyone that lives in the Bay Area again, and to reimagine what it would have looked like to reengage with the plants and the trees, to reengage with those things that are necessary for us to live.

Alan Montecillo: Five acres of Joaquin Miller Park were given to the Security Land Trust and the Confederated Villages of Lashon. This plan didn’t have any significant opposition. The process still took five whole years.

Annelise Finney: The reason why it’s taken five years to get to this place is that actually giving land back from a city is not easy.

Alan Montecillo: Today, we’re revisiting an episode from last November with Ericka Cruz Guevarra and KQED reporter Annelise Finney. We’ll hear about the appetite for returning land to Native people and why actually making it happen is so complicated.

Ericka Cruz Guevarra: Annelise, Let’s start by talking about the land itself. Can you describe for me what it looks like?

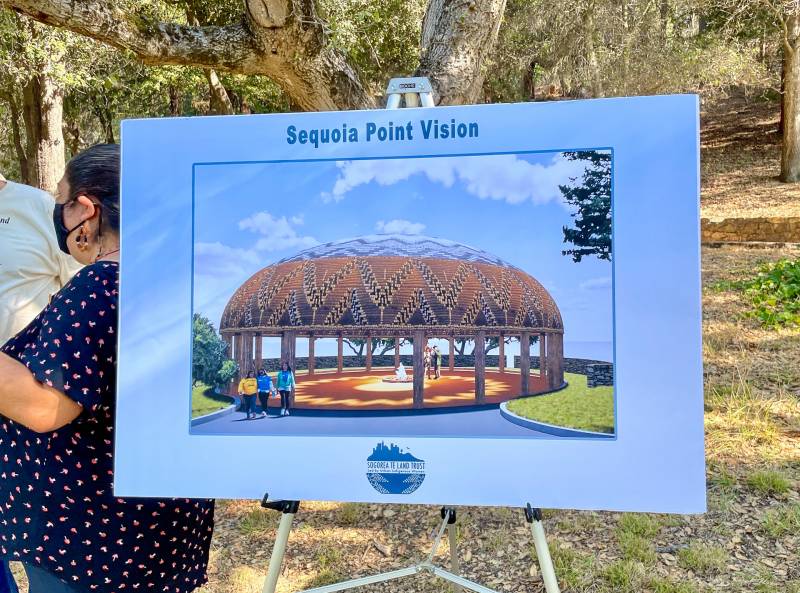

Annelise Finney: Sequoia Point is way up. And Joaquin Miller Park. It’s off of Skyline Boulevard, and it’s about five acres. If you drive into it, there’s kind of this like, padded cement area that looks like it used to be a parking lot, but it’s kind of been abandoned by the city. And all around that is this big wooded area. And through the trees you can see views of all of the east bay and then north towards the Coquina Strait.

Ericka Cruz Guevarra: Today we’re talking about this example of a city in California giving land back to native tribes. When did you find out this was going to happen?

Annelise Finney: So back in September, the city and security, which is a land trust based in the East Bay on the traditional territory of the Confederated Villages of Lushan, held a press conference in Joaquin Miller Park.

Libby Schaaf: Today we are letting healing begin.

Annelise Finney: The point of this press conference was to announce this land back plan. It’s very personal, but they’ve been working on it since 2017. So at this point, it’s been about five years in the making. But they decided to keep it kind of on the down low until they had worked out a lot of the kinks for the plan. Mayor Libby Schaaf, She did a lot of kind of the talking at the beginning and introducing sort of what this plan with security is.

Libby Schaaf: So today is a day where we acknowledge the harm that government and colonialization has done.

Ericka Cruz Guevarra: How big of a deal is this for Native American tribes in the Bay Area? Has this ever happened for these tribes before?

Annelise Finney: So in the Bay Area, there’s never been a land return that came from a municipality. There have been other land returns, but they typically have come from private property owners, some state parks and even some national parks that are kind of outside of the General Bay Area. But Pinnacles, which is sort of south of the Bay Area, closer to Monterey, has also done some work with native tribes in that area.

Corrina Gould: *introducing herself in native language*

Annelise Finney: So Corrina Gould is the co-founder of the Sogorea Te Land Trust, and she’s also the spokesperson for the Confederated Villages of Lisjan. The Confederated Villages of Lisjan, are one a loaning group based in sort of the northern part of the East Bay.

Corrina Gould: 20 something years ago, when Janelle De La Rose, the co founder of the Sogorea Te Land Trust, who stands with us today, started this work around sacred site protection in the Bay Area. And most people didn’t know the word colony. No one knew the word Alaskan. And over the last 20 plus years, we worked to protect those sacred sites and those ancestors, and they have protected us. Who knew that 20 plus years later, that land would start to come back to us? And Little Rock…

Ericka Cruz Guevarra: I want to talk about sort of the how now. I mean, we mentioned how rare this is for a city to do this. And I know that here in the Bay Area, there’s definitely an appetite for movements like land back. Has this process been hard?

Annelise Finney: Yes, it’s been very complicated. And that’s something that everybody emphasized that this press conference kind of folks from Cigarets and from the city, that the reason why it’s taken five years to get to this place is that actually giving land back from a city is not easy. And it ties into something called federal recognition, which essentially is this federal process that Native American tribes can go through to get sort of federal recognition of their tribe’s history and rights within the United States.

Annelise Finney: If you have federal recognition, you get access to federal funding for education and health care, and you also get access to sovereignty on your own land. But in California, it’s really hard to get that type of recognition. To explain this. I’m going to have to give you a little bit of a history lesson. And this may be familiar if you grew up in California, but California before it was part of the United States, was part of Mexico, and before it was part of Mexico, it was actually a Spanish colony. And during the time of Spanish rule, there was a system called the mission system.

Annelise Finney: But these missions were essentially outposts run by priests who were Spanish, and they functioned essentially like plantations in that they enslaved Native American people and involved them in forced labor. It was also a really deadly experience, in part because the labor was hard and in part because of disease that was brought to native communities that hadn’t been there before.

Valentine Lopez: The Indians would go to those missions and they’re nothing but death camps.

Annelise Finney: When I was learning a little bit more about this process and how it’s impacted federal recognition, I spoke with the tribal leader from the South Bay, whose name is Valentine Lopez. He’s the chairman of the Amah Mutsun Tribal Band, and he explained that for his ancestors, experience in the mission was incredibly detrimental.

Valentine Lopez: During that time, many of the tribes were wiped out 100%. Many of the other tribes, you know, they survived losing, you know, 96 to 90% of their of their tribal members. And, you know, and that’s the history that was never told.

Annelise Finney: The mission experience was just part one. After that, the Spanish were replaced by the Mexican government and that controlled California for a long time, during which point the Bay Area was broken up into these sort of ranch areas, these big ranches where native people were often involved in indentured servitude. And after that, the United States came in California became sort of an American state. And during this time, the government of California adopted policies geared towards the extermination of Native American people in the first State of the Union address of California. The governor at the time said he was going to wage a war against the California Indians. So for Native people, it was just wave after wave of essentially coordinated genocide.

Valentine Lopez: The state of California was largely responsible for that brutal history. And in so many ways, it’s, you know, the history of that destruction and domination of tribes never ended. It continues to this day.

Ericka Cruz Guevarra: How does that brutal history make it more difficult for tribes to eventually gain federal recognition?

Annelise Finney: In the late 1970s, the federal government created this process to try to legitimize and provide benefits to some Native American tribes. But within that process, the burden falls on native communities to sort of prove the things that the government evaluates in deciding whether or not to give federal recognition. And those things include sort of proving kind of cultural continuity throughout time, proving that there’s been a governance system over the tribe that’s continued from kind of pre 1900s through to the present.

Annelise Finney: And for Native American communities on the California coast who were subject to sort of this brutality I was describing of the California mission system, it was almost impossible to maintain that type of continuity because this stability for record keeping and providing a consistent sense of community and especially a place based community was nearly impossible. And this is something that Chairman Lopez spoke to as well.

Valentine Lopez: So, you know, with those kind of death rates and that kind of brutal history, how we supposed to stay together? You have to have an effective government system, you know, to be federally recognized. How do you have an effective government system? Well, you know, what are you dealing with is just day to day survival and brutality.

Ericka Cruz Guevarra: I mean, what does that all mean for tribes here today, including when it comes to efforts to get land back?

Annelise Finney: Essentially, that means that it’s really hard for Bay Area tribes to gain federal recognition. I mean, it’s hard for anybody to get federal recognition. The process takes 30 years. You often have to employ historians and ethnographers lawyers to help you through this process. So it’s difficult for anyone. But in California and in the Bay Area, it’s particularly hard.

Annelise Finney: And for that reason there aren’t any federally recognized, although many tribes. And if you’re not federally recognized, it’s pretty hard to own land because you as a group don’t have any more legal rights than, say, the Breakfast Club of Lafayette. So in order to work around this, a lot of Native communities in the Bay Area have started forming nonprofits or land trusts so that they’re able to hold property in a collective.

Ericka Cruz Guevarra: So it sounds like Oakland can’t give this land to these non federally recognized tribes, but they can give it to a land trust created by these tribes.

Annelise Finney: Exactly.

Ericka Cruz Guevarra: Coming up, we’ll talk about the deal between native tribes in the city of Oakland and why just giving away the land is a lot harder than it sounds.

Ericka Cruz Guevarra: So what exactly did Sogorea Te receive in this transaction with the city of Oakland?

Annelise Finney: Essentially, the way they worked out this deal is they created what’s called a cultural conservation easement. And what the easement does is it doesn’t sell the land to security. So security doesn’t have all of the property rights, but it does section off specific property rights and it transfer them to security in perpetuity, which means that essentially security owns these rights to this property forever into the future until essentially either the city of Oakland or security ceases to exist.

Ericka Cruz Guevarra: It’s not quite the same as owning the land. Right?

Annelise Finney: Right. So there are some rights that the city of Oakland will reserve on this property. One of them is the right to enforce Oakland laws. Oakland also will reserve the right to sort of help with some of the maintenance and help come up with a management plan. But on the other hand, security has the rights to sort of do any type of land management that preserves the environmental quality of the land. So if they want to do native plant restoration or they want to hold ceremony or other types of programing or educational events, all of those rights will belong to them when this deal is finalized.

Brendan Moriarty: It’s like we’re trying to do the right thing and return this land and unwind incredible oppression. And we’re dealing with an institutional environment that is in some ways racist, frankly.

Annelise Finney: Part of the reason they chose a cultural easement is because the city faces certain barriers when it comes to getting rid of public land. This thing I spoke with Brendan Moriarty about, Brendan is the real estate manager for the City of Oakland, which means that his job is to sort of manage the city’s property portfolio.

Brendan Moriarty: It’s been proving really hard to do the right thing. Know, it’s been five years that the city has been working on this and we’re only now the point where we can convey this easement back.

Annelise Finney: So if the city decides they want to sell something that is currently public land, like a section of rock in Miller Park, it triggers a bunch of state laws. And one of those laws called the Surplus Land Act requires the city government to make that land first available to any other public agency who wants it. And then if there’s no public agency who wants it, then make it available to anybody who might develop affordable housing. Because don’t forget, we are in a housing crisis here in the Bay Area in California at large.

Annelise Finney: So after that, if nobody wants it, the city is then still subject to Sequoia. Sequoia as the California Environmental Quality Act, which is a rule that essentially requires anybody making a change or selling property. Evaluate how that change might impact the environment. Sequoia has become sort of notorious for the way that it can really hold up projects. So the city of Oakland with Cigarets essentially decided that, look, we want to get this land into the hands of security and by extension, people who are part of the Confederated Villages of La Shawn as soon as possible. And it’s going to be a lot faster and a lot more convenient for us to do that through a cultural conservation easement.

Brendan Moriarty: I think we feel like they shouldn’t have so many regulatory hoops to still jump through. But it is the world we all live in. And so I think there’s probably more work to do to make things easier, frankly, for the people, for the poorest people. Giving some land back is one act, but in and of itself is not enough.

Ericka Cruz Guevarra: I do feel like I have to ask you this question, because I do imagine maybe some listeners hearing that and saying, well, I mean, is this just the government trying to pull one over on Native people again? You know, why not just give them full rights to the land? But I mean, is security okay with this arrangement.

Annelise Finney: In this case? As far as I can tell, from what security has said, they’re okay with this deal. At an event that was held by security, talking with a lot of other people who have successfully carried out land back programs in the places that they live. Corrina Gould talked about how beginning to get more access to land, especially kind of relatively unfettered access, is in a lot of ways just the first step in kind of completing this dream of having Indigenous leadership over the way we interact with the land and also centering Native people and understanding what it means to live in the Bay Area and how we can care for the environment that ultimately cares for us.

Corrina Gould: That was their staff and the city that really took this under way, did a lot of research try to figure out how to turn loss upside down so that they would work and create a model of change so that it wasn’t just for us. And we really wanted to get it right so that it could be a blueprint for other tribal people to do that in other places.

Ericka Cruz Guevarra: And what are the tribes plan to do with the land? What’s their vision for it?

Annelise Finney: Yeah. So what Corrina has emphasized is wanting this to be a space where the native communities in the Bay Area of many different tribes that people come from have as a place to hold ceremony, to learn about the environment and to reconnect with kind of sort of the native species. And and part of that is through land restoration up there. There’s a lot of non-native species that are on the on the land that are going to become part of this land transfer.

Annelise Finney: There’s also a hope to create educational programing for non-native residents of the Bay Area to also learn about native history. And ultimately there’s some hope for development. Corrina has talked about wanting to build a sort of ceremonial structure that would be on the cement pad. That’s sort of part of the parking lot that’s up there already. But that is definitely a few years down the road. I think what seems the most exciting is just the opportunity to really vision with way less limits.

Ericka Cruz Guevarra: What implications could what Oakland just did have for maybe other Bay Area cities that are interested in doing something like this?

Annelise Finney: One thing that Corrina has said and Brendan Moriarty from the city of Oakland said is that part of why they spent so long working on this is because they wanted to create a really good example for other people. And, you know, the land back movement generally has been gaining speed over the last few decades. And a few of the tribal leaders I spoke to kind of highlighted the growth in this movement since the George Floyd murder. And in California, there’s been land back from Eureka all the way to L.A.

Annelise Finney: I mean, the Tongva in L.A. now have land back, and urban land is particularly hard to come by. So what’s happening in Oakland is sort of a culmination of, you know, this idea of, okay, let’s focus our energies on returning land to native people, and there’s a role that cities can play. So I think for other folks in the Bay Area, I know many of the leaders that I spoke to are really looking to security and what’s happening in Oakland as a kind of way to push the door open even further in terms of returning land to native people here in the Bay Area.

Jonathan Cordero: So land back has to include capacity.

Annelise Finney: Jonathan Cordero is the chairman of the of Ramaytush Ohlone. That is the Ohlone Group that is traditionally from the San Francisco Peninsula. And I was asking him about land back. And one thing he said that stuck out to me was that, you know, without resources land in and of itself, isn’t that useful?

Jonathan Cordero: If you were to offer us a thousand acres today, I would say no, because we do not have the financial, legal and human resources necessary to tend that land over time. In other words, the the return of land would become a burden, not a benefit, for us.

Annelise Finney: It takes a lot of work. It takes a lot of time to restore land that ultimately what a lot of tribes need is affordable housing. I mean, I spoke with tribal leaders from the South Bay who both told me that the majority of their membership lives in the Central Valley, not in the South Bay, because they can’t afford it and because they were forced there and haven’t been able to make it back.

Annelise Finney: So for those people who are hoping that land back will also include a way for tribes to kind of return to their traditional land and live and maintain the land, that is challenging and it requires a lot of resources. And for tribes that are not federally recognized, there’s very little financial support available. And that, unfortunately, is the circumstance of most Bay Area tribes. Many of the tribal leaders that I spoke to emphasized that land back is great, but it’s just the first step.

Ericka Cruz Guevarra: Annelise, thank you so much for joining us. I always appreciate it.

Annelise Finney: Thank you.

Alan Montecillo :That was Annelise Finney, a producer and reporter for KQED, speaking with Bay host Ericka Cruz Guevarra. This conversation was cut down and edited by me, Alan Montecillo. Ericka Cruz Guevarra scored it and added the tape. Our producer is Maria Esquinca. I’m Alan Montecillo, in for Ericka Cruz Guevarra. I hope you have a safe and restful holiday. We’ll talk to you next time.