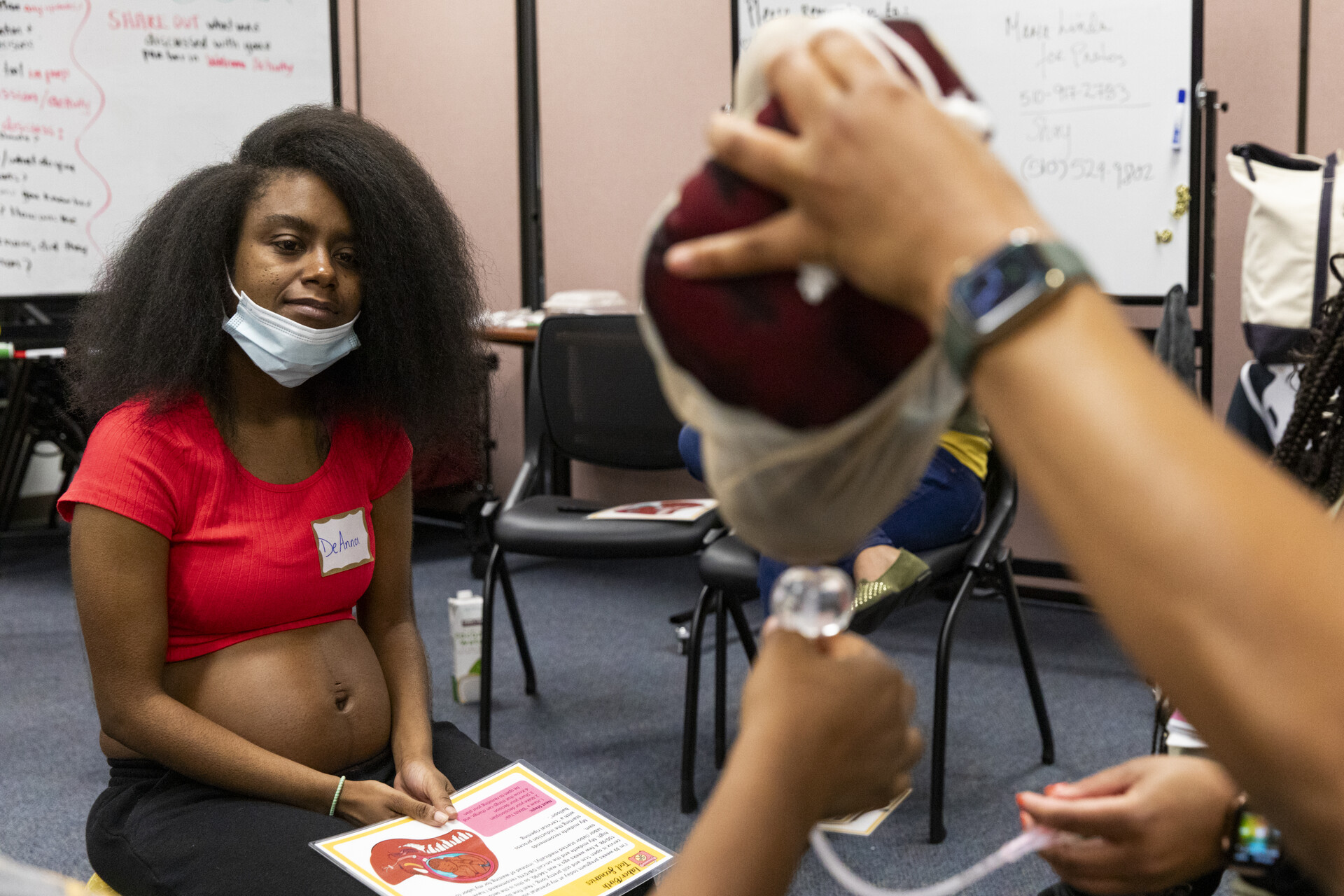

Things didn’t go as planned when DeAnna Jones, 31, delivered her first child in Oakland three years ago.

She wanted to have a natural birth, but early contractions led doctors to medically induce her labor a week earlier than her due date. Her daughter’s birth turned out well, but she wished she had known more going into the experience.

“I did have a birth plan, and getting induced was not part of that,” Jones said. “So when it came at 39 weeks to be induced, I was like, okay … but I didn’t necessarily say why or can I wait until I’m actually 40 weeks or things that I probably should have asked.”

Jones didn’t feel mistreated during her experience at the Wilma Chan Highland Hospital Campus, but it gave her pause when she became pregnant again.

So Jones was excited when, around eight weeks into her second pregnancy, she was invited to participate in a group perinatal care program that’s trying to improve the patient experience for Black women like her who live in Alameda County. The program, called BElovedBIRTH Black Centering, is resulting in healthier births and prompting state officials to look into expanding it to other public hospitals in California.

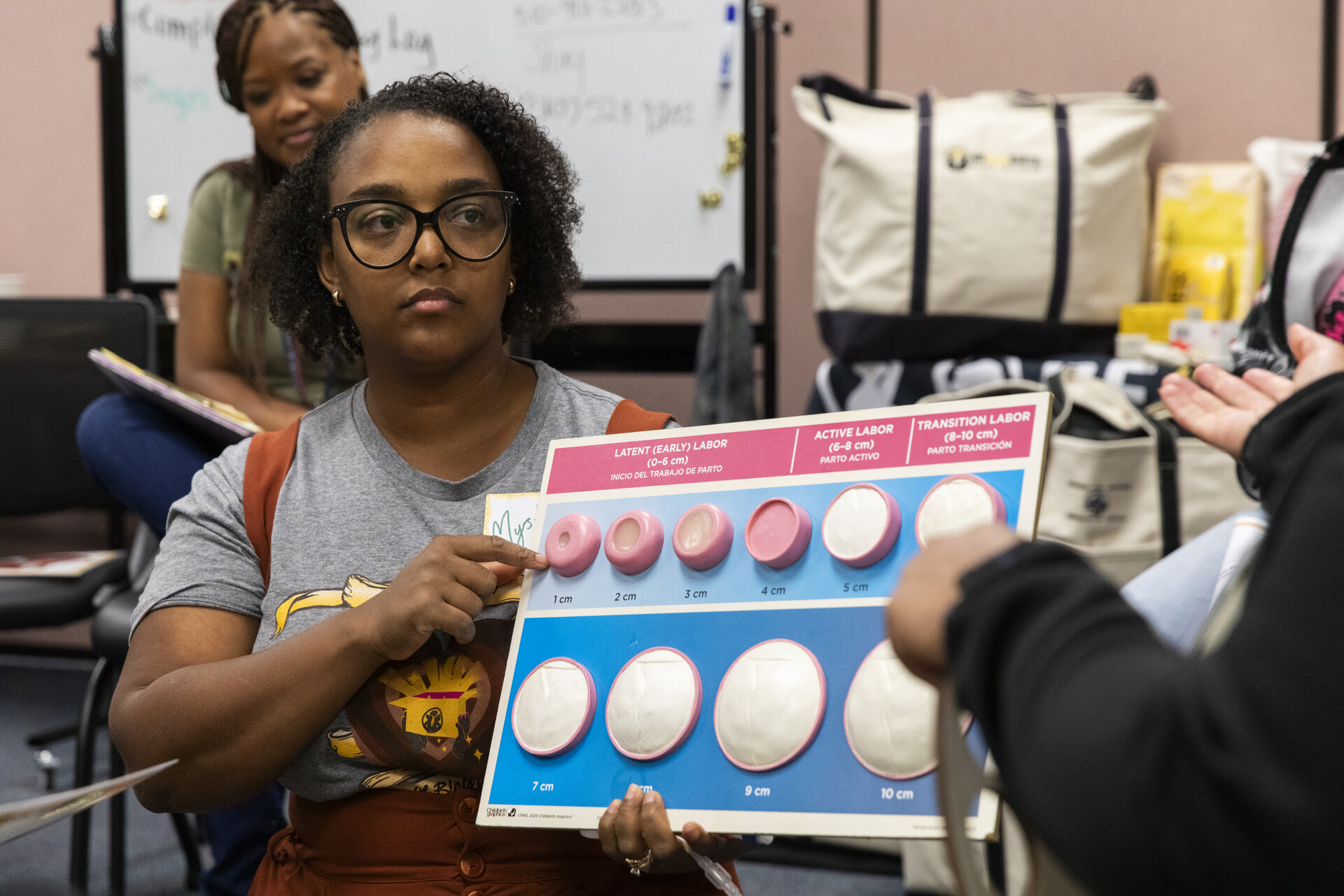

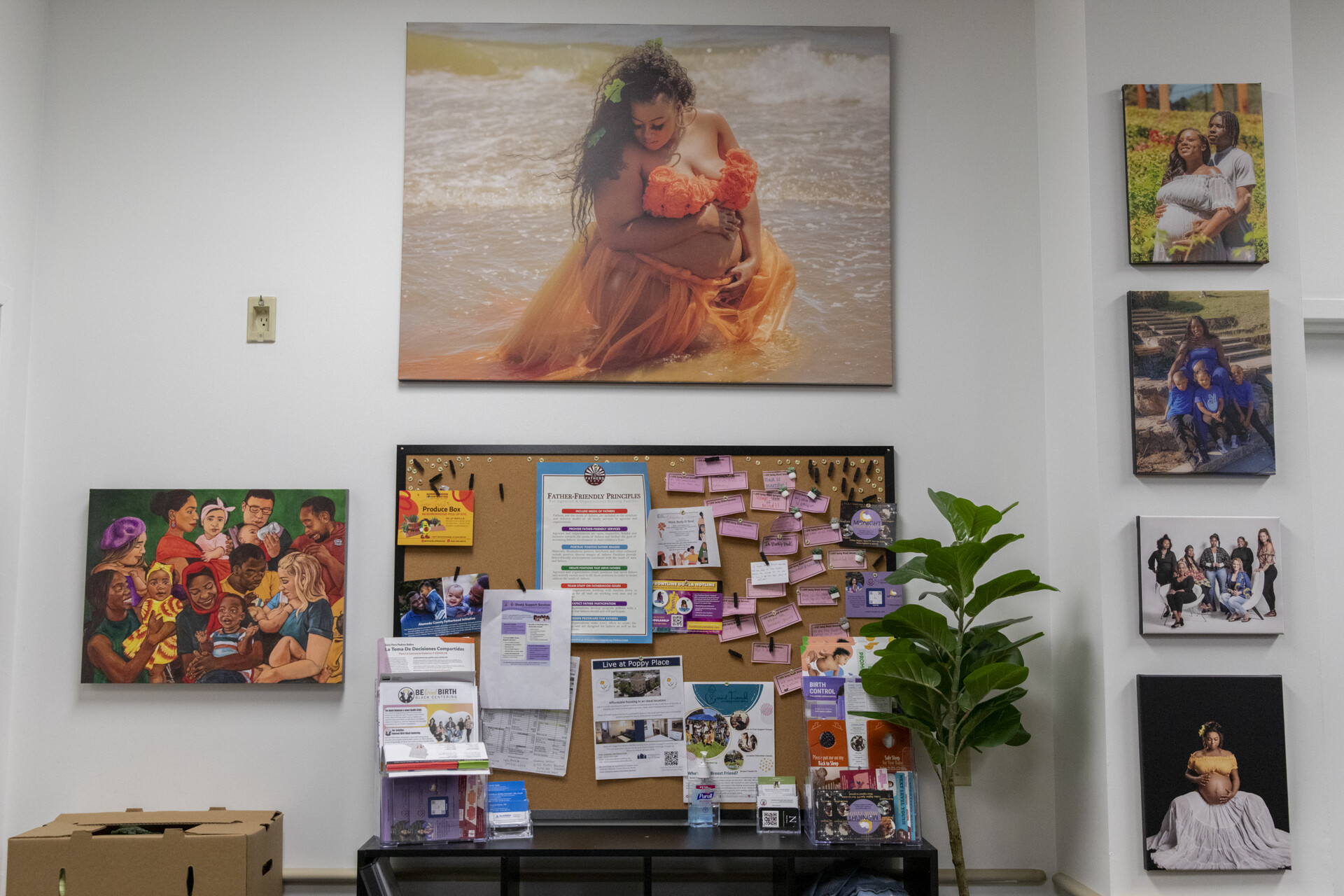

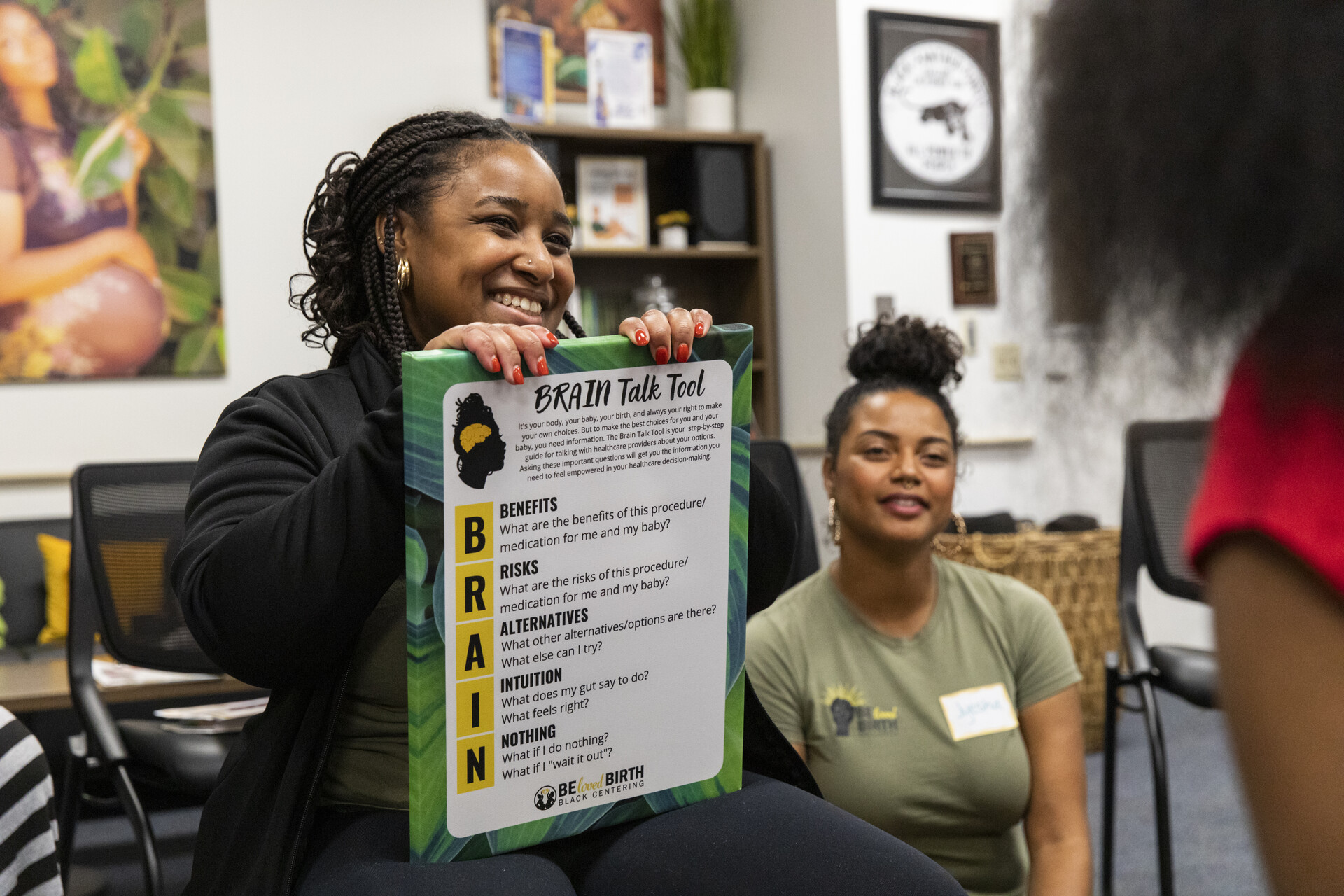

The program groups up to a dozen Black women in similar stages of pregnancy and offers them care from a team of Black doctors, midwives, doulas, nutritionists, breastfeeding experts and other wellness professionals. Participants receive a range of services before, during and after giving birth — from childbirth education to mental health support and social services.

The program also harnesses donations from the community to give away fresh produce, baby supplies, postpartum meal deliveries and pregnancy portraits with a professional photographer.

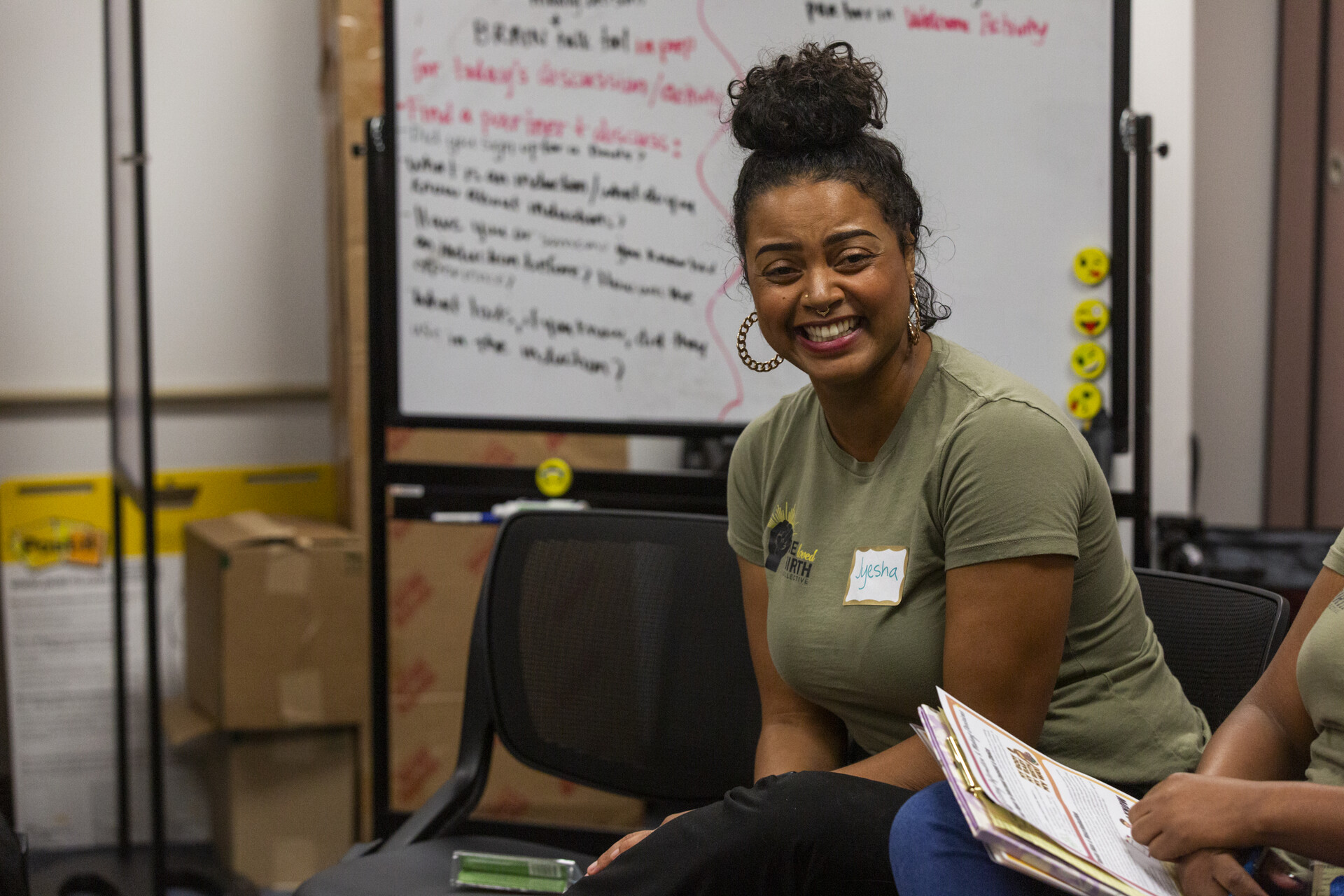

“We have really adopted the ‘it takes a village’ mindset and the commitment to say, okay, if we know better, we have to do better,” said Jyesha Wren, a midwife and director of the program.