As the county pursues its goal of ensuring that interim or permanent housing is available to every person experiencing homelessness, the ordinance takes aim at recalcitrant encampments made up of “a segment of the homeless population that just are treatment resistant and don’t want to be in shelters,” according to Slocum.

Advocates warn that’s a faulty premise and argue that simply providing enough beds to house camp residents fails to address the many reasons people experiencing homelessness might reject an offer of emergency shelter.

Some shun congregate shelters because of past trauma. Some find them unmanageable because of intellectual or physical disabilities or mental health issues, and others have pets or belongings they don’t want to leave behind.

And, crucially, shelter beds are often temporary offerings. Shelters frequently require residents to leave for hours a day and have rules that some unhoused people feel restrict their rights.

“So a person would essentially be put in the position of moving from a location where they can stably be 24 hours a day, despite its rudimentary nature, to a shelter where the setting is very temporary,” Bauman said. “Once that time comes to an end, what is that person’s alternative?”

Unless they have an offer of permanent housing, it’s likely the street — only without many of their belongings or the community they’d established.

“We know that that type of approach is destabilizing,” Bauman said. “It perpetuates homelessness, makes it harder to escape, and it’s expensive to implement.”

With limited shelter space available, she also said the proposed ordinance could end up forcing people who’ve determined shelters don’t work for them into beds that could otherwise be available to those who want to access them.

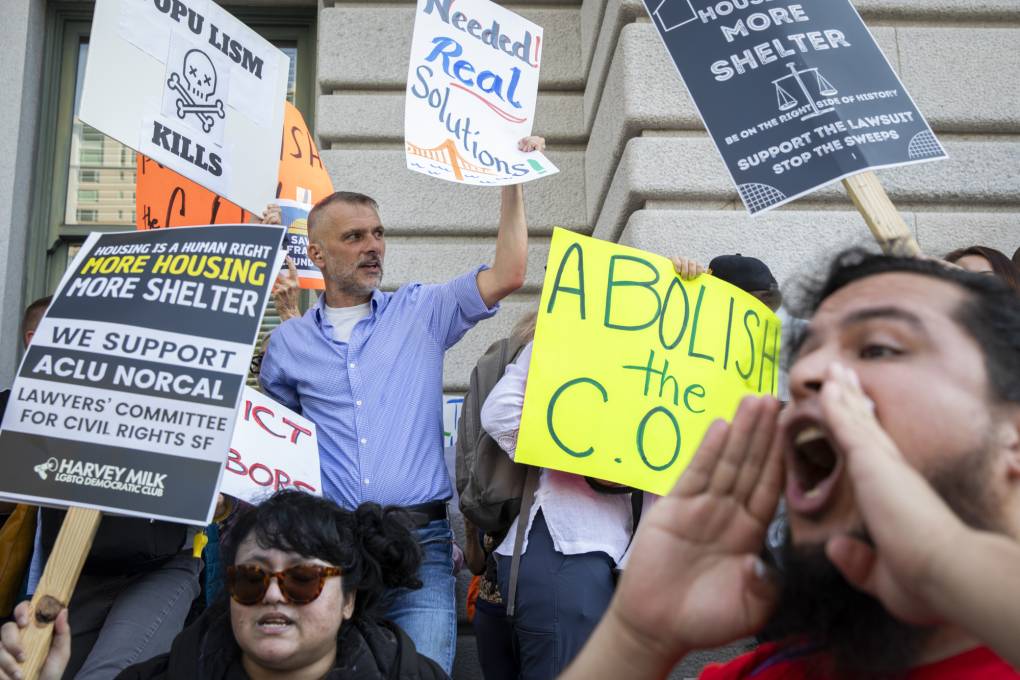

“It’s disappointing because I think San Mateo is doing a lot of things right,” said William Freeman, senior counsel at the ACLU of Northern California. “It’s inhumane to criminalize homelessness, and it increases trauma. If we’re trying to find solutions to the problem and to help people, this is the wrong approach.”

Freeman, who lives in San Mateo County, said the ACLU raised concerns with county officials about a draft of the ordinance last summer, but the current proposal reflects few meaningful changes. He worries about how the ordinance would be used in practice if it’s approved.

“It has a lot of vague terminology, and it opens up a lot of opportunities for abuse,” he said. “When you give law enforcement a tool, you open up the possibility of abuse if you don’t have really strong protections in place.”

In San Francisco, a federal magistrate granted a preliminary injunction limiting encampment sweeps, in part because of evidence that the city wasn’t following its own policies in clearing camps.

At last count, there were 1,808 people experiencing homelessness in the county, nearly a third of those on the streets or in tents. Slocum estimates the ordinance would impact about 44 people in eight encampments in the county’s unincorporated regions.

The move comes as cities around California are grappling with rising homelessness and widespread encampments and struggling to clean up their streets and move people indoors.

A 2022 court decision bars local governments from punishing unhoused people who sleep in public when no shelter is available. Earlier this month, the Supreme Court agreed to review that ruling.

Under San Mateo’s proposal, anyone charged with a misdemeanor violation under the ordinance would qualify for diversion programs offered by the San Mateo County Superior Court, which could help them avoid jail time.

“The County has worked hard to implement the goal of functional zero homelessness, whereby individuals experiencing homelessness have access to appropriate shelter opportunities,” Pine, who introduced the proposal alongside Slocum, said in a statement. “This proposal helps incentivize individuals to take advantage of these opportunities in a compassionate way while also regulating critical operational details.”

The Board of Supervisors will meet at 9 a.m. Tuesday.