Immigrant students’ schoolwork and experience in the classroom often suffer in the presence of immigration enforcement — with 60% of teachers and school staff reporting poorer academic performance, and nearly half noting increased rates of bullying against these students, UCLA-based researchers found.

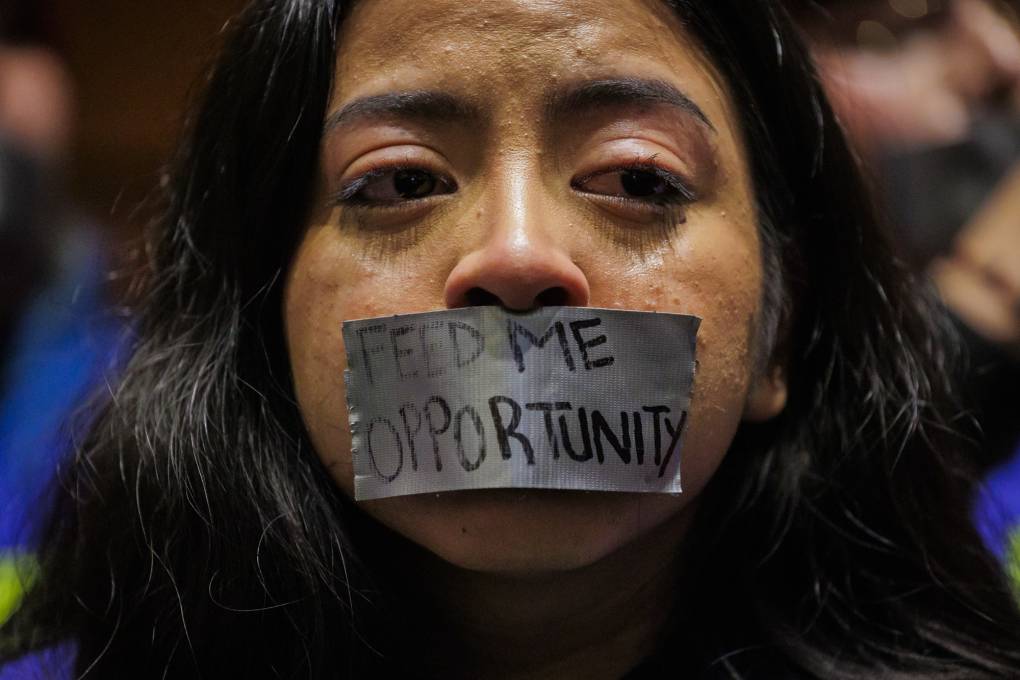

“Instead of focusing on their education, these students struggle with this uncertainty and, as a result, are often absent from school or inattentive. Their teachers also struggle to motivate them and sometimes to protect them,” reads a recent policy brief by UCLA’s Center for the Transformation of Schools, Latino Policy and Politics Institute, and Civil Rights Project/Proyecto Derechos Civiles.

“The broken immigration system hurts schools and creates victims across the spectrum of race and ethnicity in the United States, but it is especially acute for these students.”

According to UCLA’s policy brief, children of “unauthorized immigrants” between the ages of 6 and 16 are 14% more likely to repeat a grade, while those aged 14 to 17 are 18% more likely to drop out of school altogether.

One of the most common reasons for students to miss class or drop out is the pressure to work full time to support family members financially, said Yesenia Arroyo, the principal of LAUSD’s RFK School for the Visual Arts and Humanities, where roughly 80% of students are immigrants.

She added that she works closely with her school’s counseling staff to connect regularly with students about their academic progress. They also try to find Linked Learning opportunities, where students develop real-world experience, and paid internships — which can help students earn while remaining in school or pursuing their interests.