She said things changed when Roe was overturned. She went to a rally in 2022 and heard women talking about deleting period-tracking apps out of fear of how their data could be exploited.

When she introduced a health-specific data privacy bill last year, it wasn’t just lawyers and lobbyists testifying; women of all ages and from many walks of life showed up to support it, too.

The measure, which bars selling personal health data without a consumer’s consent and prohibits tracking who visits reproductive or sexual health facilities, was adopted with the support of nearly all the state’s Democratic lawmakers and opposition from all the Republicans.

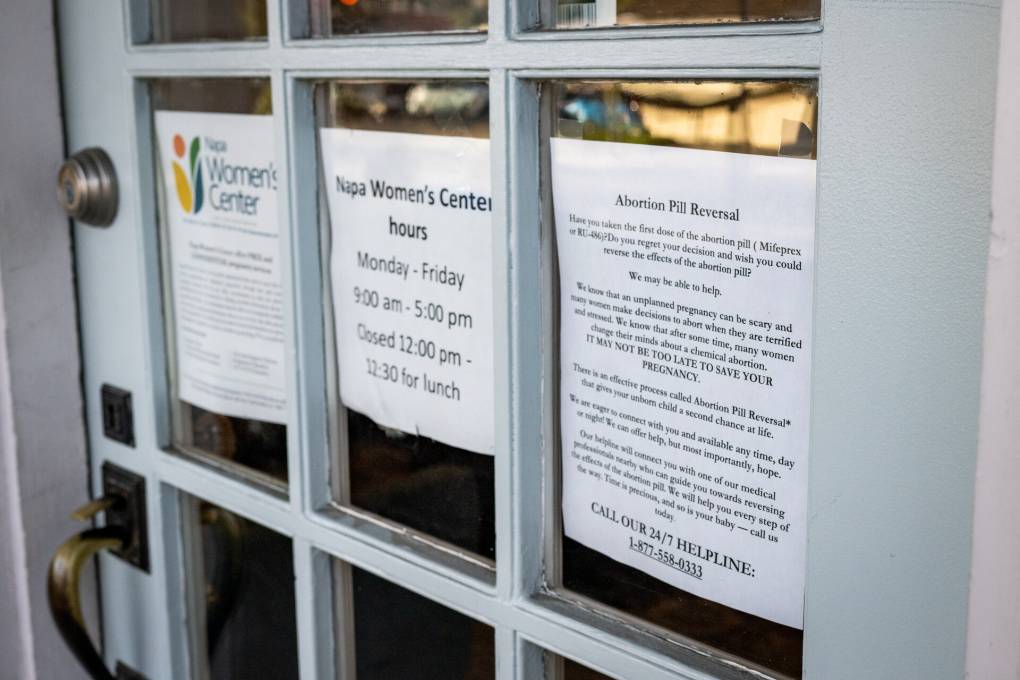

Connecticut and Nevada adopted similar laws last year. New York enacted one that bars using tracking around health care facilities.

California and Maryland took another approach, enacting laws that prevent computerized health networks from sharing information about sensitive health care with other providers without consent.

“We’re really pushing forward with the free-flowing and seamless exchange of health care data with the intent of having information accessible so that providers can treat the whole person,” said Andrea Frey, a lawyer who represents health care providers and digital health systems. “Conversely, these privacy concerns come into play.”

Illinois, which already had a law limiting how health tracking data — measuring heart rates, steps and others — can be shared, adopted a new one last year that took effect Jan. 1 and that bans providing government license plate reading data to law enforcement in states with abortion bans.

Bills addressing the issue in some form have been introduced in several states this year, including Hawaii, Illinois, Maine, Maryland, Massachusetts, Missouri, South Carolina and Vermont.

In Virginia, legislation that would prohibit the issuance of search warrants, subpoenas or court orders for electronic or digital menstrual health data recently cleared both chambers of the Democratic-controlled General Assembly.