Episode Transcript

Olivia Allen-Price: The East Bay hills above Berkeley and Oakland are crisscrossed with beautiful hiking trails. Darrell Lavin, today’s question-asker, loves to explore them.

Darrell Lavin: My cousin lives right over in that area right near Leona Lodge. And so I go over there and hike with her all the time.

Olivia Allen-Price: One day, they tried a trail he’d never been on before. Halfway up they came upon something unexpected.

Darrell Lavin: It looks like it was some sort of a very significant structure many, many years ago. And it looks like there had to be some sort of a cabling system there to haul stuff up and down the hill.

Olivia Allen-Price: Darrell figured his cousin would know what these ruins were, but she had no idea.

Darrell Lavin: And they’re all covered in graffiti. And the artwork is beautiful. And I can’t help but wonder, what’s the history of this, what was there and what was it used for?

Olivia Allen-Price: Darrell’s question won a Bay Curious voting round, so today we’re hiking up to these ruins near Leona Canyon Regional Park… to learn what was there more than a hundred years ago. And we’ll find out a bit more about that beautiful artwork that Darrell described. I’m Olivia Allen-Price. Stay with us.

SPONSOR MESSAGE

Olivia Allen-Price: KQED Reporter Katherine Monahan loves hiking and mysteries, so she was the perfect person to send on an expedition to find out the history of these ruins in the Oakland hills and how they’re being used now.

Footsteps in the woods

Katherine Monahan: I’ve been hiking around for half an hour, looking for these ruins, when I see a flash of bright pink peeking through the oak trees that line the trail. I duck under a branch . . . and enter a clearing scattered with concrete walls. One of them is as big as a bus; others are small, like traffic barriers. All of them are painted with really good murals.

Andrew Alden: And they built it well because the concrete is still in great shape.

Katherine Monahan: Andrew Alden, a geologist and local historian, meets me here. He’s a sprightly guy with a ponytail and gemstone earrings. He points out a clue to why these ruins are here. It’s a reddish rock, about the size of a mailbox.

Andrew Alden: I think it’s just beautiful by itself.

Katherine Monahan: What is it?

Andrew Alden: It started out as volcanic ash on the seafloor. It got involved in a lot of tectonic action, and it changed the rock into this very hard light-colored, very strong material that gets this honey-colored orange and red coating on it.

Andrew Alden: Geologists used to call it the Leona laterite. Now we just call it Leona Volcanic.

Katherine Monahan: Alden says that in the late 1800s, when Bay Area cities were growing, rock like this was very much in demand.

Andrew Alden: Crushed stone is a basic requirement of civilization. You just need it for everything. You need it for railroad beds, you need it for building foundations, you need it to build harbors and wharves.

Katherine Monahan: People punctured the East Bay hills with mines and quarries, looking for pyrite, sulfur, gold, though they didn’t really find any, and just rock.

Andrew Alden: They started quarries wherever the rock was good just to make money from these hills.

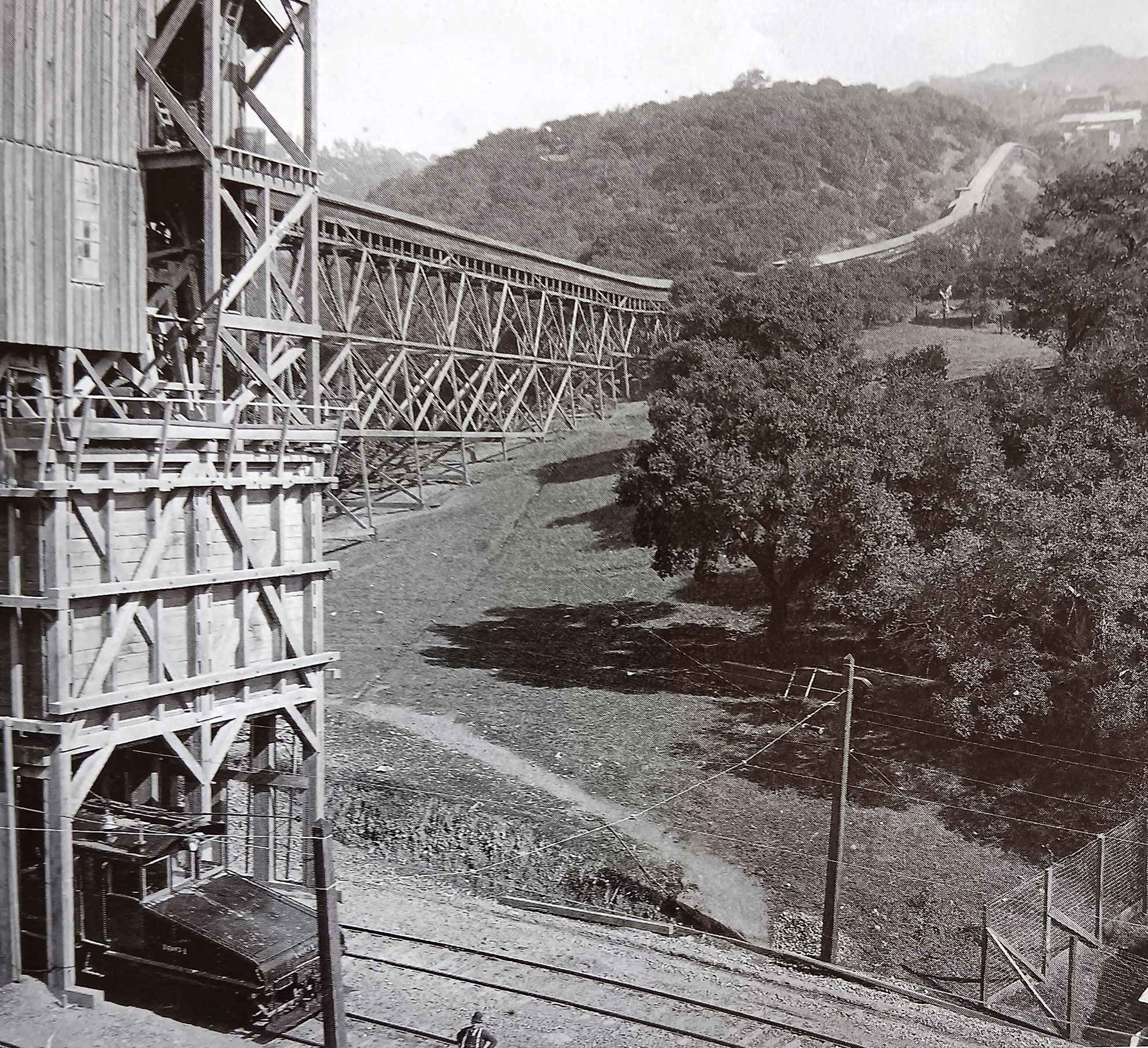

Katherine Monahan: The ruins we’re looking at were part of the workings of the Leona Heights Quarry, says Alden, which was where Merritt College is today. Workers dynamited rock from pits and loaded it onto a conveyor tram leading down the hill.

Andrew Alden: It would send stone down to the electric train tracks.

Katherine Monahan: It was a half-mile-long conveyor belt running on a wooden trestle. It looked kind of like an old-fashioned roller coaster. Historical records suggest its machinery was housed right here in this concrete. Slots in the walls probably framed the wheels that turned the belt.

Katherine Monahan: This tram helped make the whole operation possible but would ultimately destroy it.

Voice Reading Newspaper Report: Oakland Enquirer, Aug. 8th, 1913 — Leona Fire Causes Big Loss, Town Is Menaced.

Katherine Monahan: A fire broke out near the base of the tram and ignited the conveyor belt, which carried the flames up the hill. The newspaper said the wooden trestle was “dry as tinder.”

Voice Reading Newspaper Report: Stores of dynamite and powder in sheds in the path of the fire spread the blaze with great rapidity. Until long after midnight the fires burned in the ravines of Leona Heights, to which blazing brands had been carried by the high wind. That no fatalities occurred was considered remarkable.

Katherine Monahan: All the buildings and tools were incinerated, a quarter million dollar loss and a huge blow to the quarry. By the 1930s, it showed up in the papers mainly as a place where convicts hid out or kids got lost. Here’s Andrew Alden again.

Andrew Alden: Cheaper stone arose out of town, you know, quarries and cities can’t really coexist. Oakland has spread out.

Katherine Monahan: Eventually, the quarry was filled in and is now a Merritt College parking lot.

Andrew Alden: There used to be a great big pit there they called Devil’s Punchbowl and all the local kids would get in trouble there. They’d push old cars into it and throw dynamite sticks and that kind of thing.

Katherine Monahan: And what’s left of the conveyor tram …

Andrew Alden: As you see, the artists have adopted it. And it belongs to the future as well as the past.

Modern music transition

Katherine Monahan: The concrete walls here have been painted over many times by many artists. One of them has been coming here for almost thirty years.

Pancho Pescador: My name is Pancho Pescador. I’m originally from Chile. I always painted since I was a kid.

Katherine Monahan: He says he found this place by accident back in 1995, not long after he moved to the United States. He was out hiking by himself.

Pancho Pescador: And I remember coming here and seeing the wall. Unexpected, because you’re in the middle of the forest and then you find all these ruins.

Katherine Monahan: They had murals on them even then.

Pancho Pescador: I was like, “What? Who paint this? This is so cool. Oh, he did it with spray paint?”

Katherine Monahan: Graffiti art was still pretty new to Pescador at the time. He’d seen very little of it growing up in Chile.

Pancho Pescador: Because we have a dictatorship, so it was more repression. You know, if you get caught painting in the street, you may get disappeared or, or dead.

Katherine Monahan: That was during the regime of Augusto Pinochet, who came to power in 1973 following a U.S.-backed coup. Through the 70s and 80s, thousands of Chileans disappeared or were killed under his rule, and almost 40,000 were held as political prisoners. Pescador says street artists of the day restricted themselves to political messages.

Pancho Pescador: They didn’t write their name, you know, like, “Oh, Pancho was here” or, you know, like, they’re risking their life.

Katherine Monahan: He shows me one of his pieces, a larger-than-life self-portrait, on a decaying chunk of concrete wall. It’s a figure with the head of a bird carrying a paint roller.

Pancho Pescador: That’s the weapon. You know, like, the weapon doesn’t have to be an M16. It could be a paint roller, so he’s a warrior because he’s carrying his weapon.

Katherine Monahan: The painting has been here for about two years, which Pescador says is a long life for a piece up here.

Pancho Pescador: You paint here, you know that you’re gonna get covered. That’s part of the game. It’s no crying, like, “Oh, you paint over me?” No, this is not the place, you know, you paint here, you know what’s going to happen.

Katherine Monahan: But there are exceptions. On the biggest wall — which is about the size of a semitruck — is a long, vibrant painting of a woman, and an AC Transit bus, and the word “Ghost.” Pescador explains it’s a memorial.

Pancho Pescador: A tribute to Ghost which was a writer from Oakland that unfortunately passed at a very young age, and some of her friends and homies did this piece to honor her.

Katherine Monahan: He says this piece will last because artists won’t normally cover up a memorial.

Pancho Pescador: This is not going anywhere. I doubt anybody’s going to paint over this. I’m not gonna do it.

Katherine Monahan: He says this is a special place, different from your average graffiti site. Up here in the trees, you have time to do big, intricate pieces with lots of colors. It’s not like painting downtown, where you might get caught. And the hike screens out a lot of artists.

Pancho Pescador: You gotta be in shape. Because you’re gonna carry your backpack full of paint, probably a couple gallons of paint, roller, all the tools, water, it gets heavy. So you know, like, you need a certain special energy to do it.

Katherine Monahan: Pescador says he loves painting up in these abandoned ruins.

Pancho Pescador: I like decay. And I like seeing my pieces getting old. I find beauty on that, a place that could be dark. And you know when you paint it, you change the energy. You do all the work for that, you know, like you see the place change, and it’s like, “Oh, yeah!” and then people appreciate it, you know?

Katherine Monahan: Through over a century of massive change around it, this place has adapted from rock quarry to outdoor art gallery. Who knows what it may become next or what it will see in the next century?

Olivia Allen-Price: That was KQED’s Katherine Monahan. Thanks to Darrell Lavin for asking the question we answered today.

Olivia Allen-Price: This Saturday, March 2 is one of my favorite events of the year. It’s the Night of Ideas at San Francisco Public Library’s Main Branch. If you haven’t been … know this: it’s a mashup of artists, leading thinkers and cultural organizations all thinking about the future — and how city life can be more just, culturally vibrant, and sustainable. Bay Curious will be there this year, hanging out in the bookmobile. Stop by to share your personal transit tales with us and the podcast Muni Diaries. We’re teaming up to collect your stories and I can’t wait to hear what you might have for us. Find details and register for free at KQED.org/Live. I’ll see you there.

Olivia Allen-Price: If you enjoy Bay Curious, tell another podcast-loving friend all about us, please! Word of mouth is one of the best ways for us to grow the show. Thank you!