California regulators have failed to compel the state’s worst cited wage theft offender to pay the millions of dollars his companies stole from workers, a KQED investigation found.

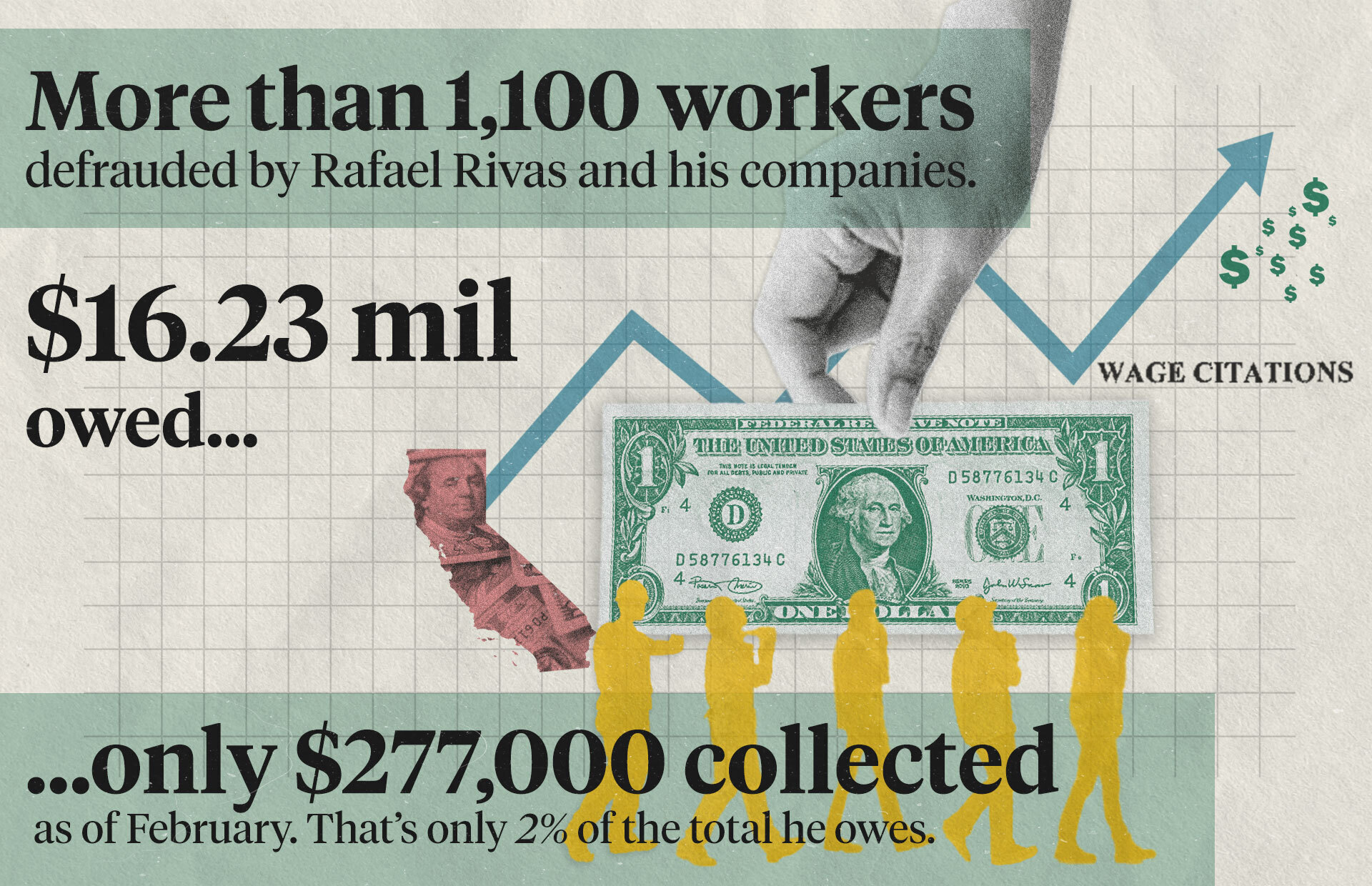

The California Labor Commissioner’s Office ordered Rafael Rivas’ RDV Construction Inc. and RVR General Construction Inc. to pay $16.2 million for defrauding more than 1,100 workers in Southern California. But the agency, which issued the citations for back wages and penalties in 2018 and 2019, had recovered just 2% as of last month, according to a department spokesman.

KQED reviewed hundreds of pages of state documents and court records, knocked on doors of properties linked to Rivas and interviewed workers the construction contractor cheated to piece together an accounting of the stunning labor violations — and how an understaffed agency was unsuccessful in collecting most of what Rivas and his companies owe.

California has some of the nation’s strongest employee protections on the books, including against wage theft. Yet, Rivas’ case signals that the state is not prioritizing restitution for workers when their earnings are withheld, according to workers’ rights advocates and employment attorneys.

“It’s outrageous. It’s infuriating,” said Benjamin Wood, a former organizer with the Pomona Economic Opportunity Center who has helped dozens of workers file wage complaints with regulators, including against RDV. “The state has so much power to enforce laws. But when it comes to massive wage theft, it seems like they’re powerless.”

From 2017 through 2023, the labor commissioner’s Bureau of Field Enforcement assessed $450.6 million in unpaid wages and penalties against thousands of employers statewide, including Rivas’ companies. The agency recovered as little as 16%, or $74.5 million, according to records it provided to KQED last month.

The database, however, may contain errors and omissions, according to a department statement. A state employee familiar with the bureau’s case management system said that’s because staff don’t consistently update it.

Beth Ross, an employment attorney, said the omissions point to a dysfunction at the Labor Commissioner’s Office, which has a critical role in protecting vulnerable workers from abuses and helping to level the playing field for law-abiding employers.

“If the agency is not capable of keeping the database updated, then what else is the agency not able to get to?” said Ross, an adjunct professor at UC Law San Francisco. “We know the agency has a very difficult time keeping up with the onslaught of complaints and tips it receives about wage theft and labor law abuse in the state.”

The job vacancy rate at the Labor Commissioner’s Office reached 42% last year, according to an analysis of staffing documents kept by the state Department of Finance. Dozens of wage theft investigators, attorneys and others at the agency implored state lawmakers in July to address a hemorrhaging of employees leaving for better-paid positions elsewhere.