Episode Transcript

Olivia Allen-Price: Every year on April 18th… at 5:13 in the morning…. San Franciscans gather at the corner of Market and Kearny Streets to remember.

Bob Sarlatte: Once again, you crazy folks have come together at this ungodly hour to remember and honor the memories of those hearty San Franciscans who survived being tossed from their beds 117 years ago this morning.

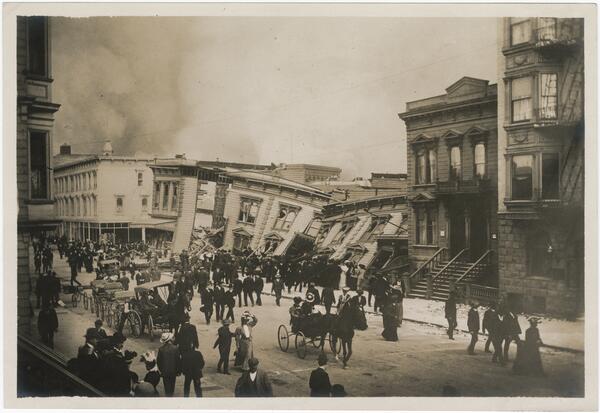

Olivia Allen-Price: People come dressed up in period costumes…trying to inhabit the moment in 1906 when an earthquake with an estimated magnitude of 7.9 brought devastation to the city.

Bob Sarlatte: Wednesday, April 18th, 1906 5:12 a.m. A great foreshock is felt throughout the San Francisco Bay area.

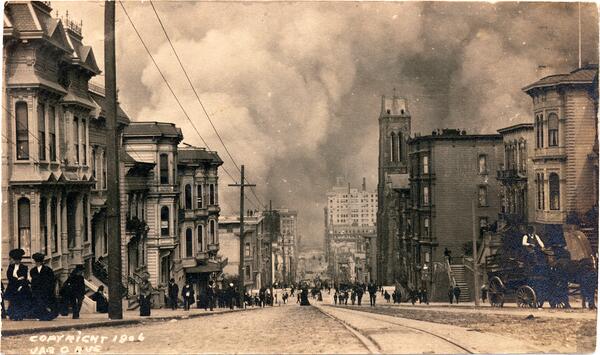

Olivia Allen-Price: San Franciscans startled awake …only to see their city burning.

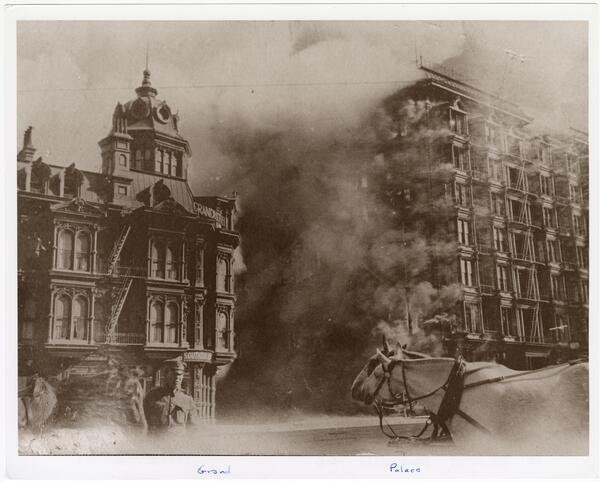

Bob Sarlatte: Fires rage and spread throughout the city. They are not stopped until 74 hours later. Many of San Francisco’s finest buildings collapse under the firestorms. Firefighters begin dynamiting buildings to create firebreaks.

Olivia Allen-Price: But the fire kept leaping over the lines, traveling further west.

Bob Sarlatte: The Great Fire reaches Van Ness Avenue, which is 125ft wide, facing the decision to blow his city to pieces or watch it burn, Mayor Schmitz finally agrees to let the army create a massive firebreak in the hopes that it can stop the raging inferno. Friday, April 20th, 1906 5 a.m. The fire break at Venice finally holds and the westward progression of the inferno was halted.

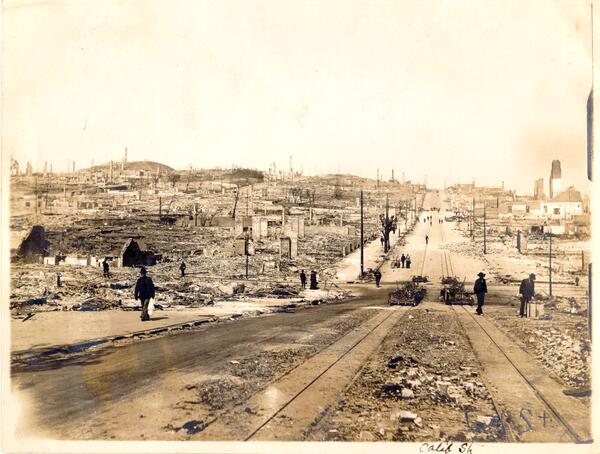

Olivia Allen-Price: It took more than three days to fully put the fire out. And then San Franciscans took stock. Nearly 80-percent of the city had burned.

Bob Sarlatte: So if we can just have a moment of silence for those who died and those who helped with the city after the earthquake. (Silence) Let’s hear those sirens go. Here we are.

Olivia Allen-Price: The Great Earthquake and fire of 1906 were devastating to everyone living in San Francisco at the time, including its several thousand Black residents.

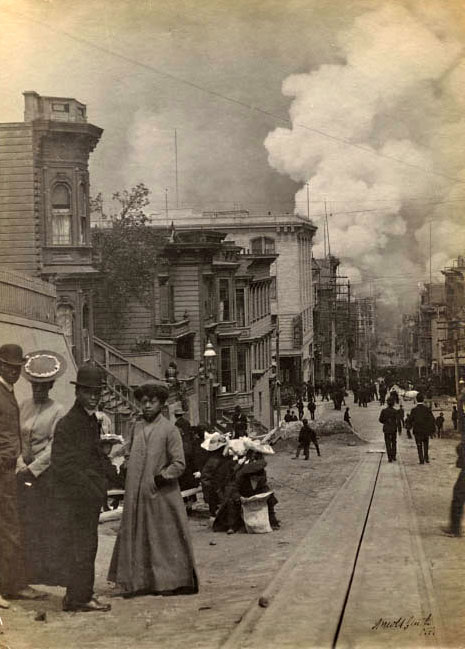

Bay Curious listener Allison Pennell started wondering about how this community fared after the earthquake when she saw an old photo in a museum booklet. It showed a group of Black San Franciscans standing at the top of Clay Street, watching the fire burn.

Allison Pennell: And I just started to think about that photograph and what would have happened after the earthquake. I know many people came over to the East Bay, and they simply got into boats and got over here, to try to set up an emergency situation over here. And so I thought, how did that work? Because, you couldn’t just probably as a nonwhite person go to the Claremont Hotel and say, I’d like a suite. At that time, the discrimination was deep.

Olivia Allen-Price: She wanted to know more.

Allison Pennell: I’m interested to know what Black San Franciscans did to survive after the 1906 San Francisco earthquake and how they re-established themselves either in the East Bay or back in San Francisco.

Olivia Allen-Price: Today on Bay Curious, on the anniversary of the Big One, we’ll hear some first person accounts from those who survived the 1906 earthquake and fire. And we’ll learn how their stories are still inspiring Black San Franciscans generations later. I’m Olivia Allen-Price. Stay with us.

SPONSOR

Olivia Allen-Price: Stories and photos of the devastation wrought by the 1906 earthquake and fire are all around us in San Francisco. But it’s less common to see or hear explicit references to how the Black community fared after the quake. Bay Curious editor and producer Katrina Schwartz set out to learn more.

Sound of elevators at the library

Katrina Schwartz: You can find all kinds of cool stuff at the public library.

tanea lunsford lynx: I was thinking like, where do where does the ephemera live? Where do the things live that we can’t touch? What are the less visited things of the library?

Katrina Schwartz: tanea lunsford lynx was recently an artist in residence at the San Francisco Public Library,

tanea lunsford lynx: And then I found that there was an oral history project that had over 25, recorded oral histories.

Katrina Schwartz: She was transfixed by the voices of Black Americans describing life in San Francisco at the turn of the 20th century.

tanea lunsford lynx: yea, we were here.

Katrina Schwartz: Now, tanea and I are standing in front of a display case on the third floor of the main branch …busy library life bustling around us.

tanea lunsford lynx: I wanted folks to kind of happen upon it outside of the elevator. So when folks kind of get out there, struck by the photos that many of us have never seen. Of the 1906 earthquake.

Katrina Schwartz in scene: Yeah. Some people have seen some of the photos, like of the fire and stuff like that. What’s different about these ones?

tanea lunsford lynx: These photos are different because they’re featuring black American folks who were here in San Francisco at the time of the 1906 earthquake. So you not only see the plume of the fires, the smoke in the back of the photos, but you also see, black San Franciscans at the forefront of the photos who are, like, dressed very beautifully.

tanea lunsford lynx: My name is tanea lunsford lynx. I’m a writer and artist and educator. And fourth generation, like San Franciscan on both sides.

Katrina Schwartz: For Tanea, these photos were a revelation.

tanea lunsford lynx: So even though my family has a deep history here, and even though we knew we were here, there hadn’t been like photo proof that I’d seen a lot.

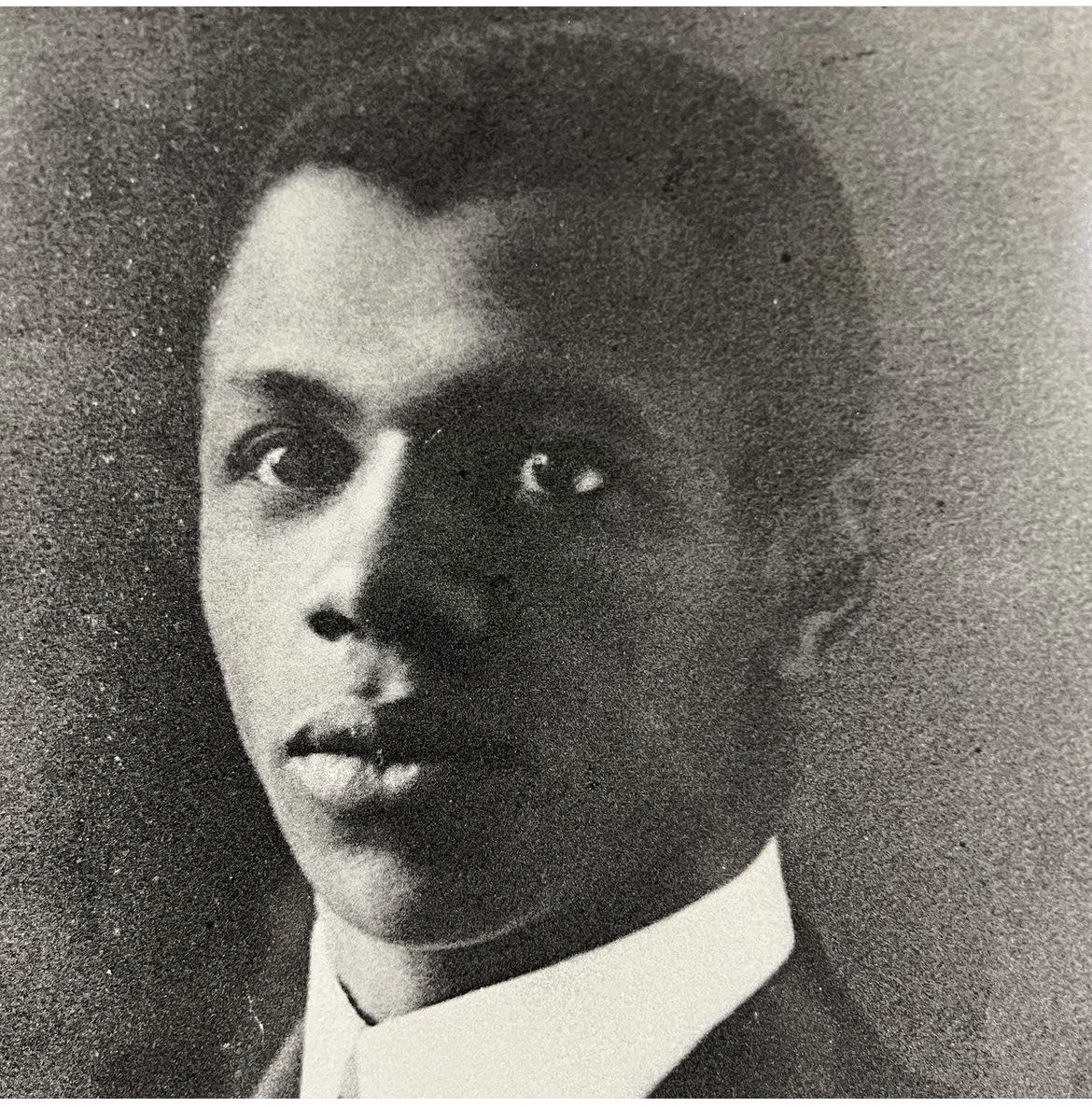

Katrina Schwartz: As part of her residency at the library she began digging into the archives kept here and stumbled across an oral history recorded in 1978… of a man named Aurelius Alberga. A black man and a survivor of the 1906 earthquake.

tanea lunsford lynx: And there certainly hadn’t been stories in our own voices about the experience of being here in 1906 and prior to that.

Music

tanea lunsford lynx: I felt a kinship pretty quickly. Because something about. Alberga’s tone reminded me of my grandfather’s voice and something about the quality of the audio is…Very appropriate for the time that it was recorded. And so you can, like hear the hum of the machine. You can hear like background noises, like I was I was automatically seated in someone’s house, like listening to them tell their stories. And it was that kinship, that closeness, that sense of intimacy that I was looking for.

Aurelius Alberga: October 22, 1884.

Dr. Albert Broussard: Where were you born?

Aurelius Alberga: San Francisco

Dr. Albert Broussard: What about you parents. Where were they born?

Aurelius Alberga: My father was born in Kingston, Jamaica. May mother was born in San Francisco.

tanea lunsford lynx: He was very chill, for lack of a better word, about surviving that earthquake.

Katrina Schwartz: Historian Dr. Albert Broussard recorded this oral history when Alberga was in his 90s. On the day of the Great Earthquake, Alberga was in his early 20s, sleeping in a room he rented at the corner of Commercial and Kearny Streets.

tanea lunsford lynx: Aurelius Alberga is asleep in his apartment, which most likely was an SRO, single room occupancy. And he lived there, and his father lived in the apartment above him.

Aurelius Alberga: My father was living there too. He had a room right upstairs directly over me. The Quake loosened and one side of the building collapsed. The doors in those days used to open out, and the door to my room was jammed shut — I couldn’t open it, you see.

tanea lunsford lynx: He, like, yells for his father to know where he is, and his father comes down and helps him get out.

Katrina Schwartz: After escaping his small room, Alberga and his father go their separate ways. Alberga is worried about the man he works for who is blind.

tanea lunsford lynx: Alberga’s job at that time is being a chauffeur for a man he calls old Metzger, who’s a man that he works for, who’s, like, wealthy, who’s a blind man. And, he develops this relationship with kind of like, caring for him in different ways.

Aurelius Alberga: He lived on O’Farrell Street between Stockton and Powell. The whole front side of the hotel had fallen out into the streets and left exposed the rooms on that end. He was right there.

tanea lunsford lynx: And so Alberga is like, oh my gosh, I hope he’s okay. And he gets up to Metzger’s apartment. And this man is sleeping.

Aurelius Alberga: He slept through it all, which was a blessing.

Katrina Schwartz: After heroically saving Metzger’s life, he takes the old man to his mother’s house. Old Metzger is worried about savings he’s got stored in a safe downtown so he sends Alberga to retrieve the money. That errand takes Alberga all over the town and he watches as the city is destroyed. He recalls how the water mains were broken and firefighters struggled to contain the blaze.

Aurelius Alberga: They had no water, and no hoses long enough to draw water from the Bay. There’s nothing that could stop it. It just went ahead.

tanea lunsford lynx: It blew my mind that he could recall with precision the exact intersections of where things happened in San Francisco, particularly as a man of, like, more than 90 years old. Because I’m also aware of, like, yes, this was a trauma that he survived. And he was able to recall with such clarity where these things happened.

Katrina Schwartz: Alberga had lost everything in the earthquake and fire, his home, all his possessions. He bounced around the city, staying with friends.

tanea lunsford lynx: One of the things he did say was that folks across like, race and ethnicity were really welcoming to each other as far as, like, inviting folks to literally stay in their homes.

Aurelius Alberga: I don’t think there were any people as friendly as the ole San Franciscans.

Katrina Schwartz: No one as friendly as ‘ole San Franciscans. People were dragging their trunks down the road, nowhere to sleep…

Aurelius Alberga: People were dragging their trunks along the street and someone would come along and help them. They’d take someone in their house they had never seen before in your life.

Katrina Schwartz: Folks opened up their homes to people they’d never seen before in their lives.

tanea lunsford lynx: So that mutual aid and that care was something that Alberga named as something that was distinctly San Franciscan at the time, that it was a very friendly place at that time, particularly after this moment of crisis. And so that really stood out to me, too.

Music transition

Katrina Schwartz: Elizabeth Fisher Gordon was just a little girl of nine-years-old when the earthquake struck. Her family lived in a flat in downtown San Francisco. But by 1906 many Black San Franciscans had relocated to the East Bay in search of more space and less expensive housing. Her grandmother lived in Oakland and Elizabeth had gone to stay with her for the Easter holidays, just before the quake.

Elizabeth Fisher Gordon: And my mother came over later in the week and brought the rest of the children. My father came over on the last boat before the earthquake hit, to my grandmother’s. I was so sure it was my fault because I didn’t kneel that night before I said prayers. I got into bed and then said my prayers because it was so cold. But I didn’t tell anyone that it was my fault the earthquake came.

Katrina Schwartz: Elizabeth remembers all the chimneys in Oakland falling down during the earthquake. As morning dawned, chaos reigned and authorities would not let Elizabeth’s father return to San Francisco on the ferry. He had to get special permission to go check on their house.

Elizabeth Fisher Gordon: And when he went over, he found out there was a whole lot of damage. But he was able to get a suitcase and put some things in it, never dreaming the fire would reach there, you know. And some of the things he brought were so insignificant my mother thought. I’ll never forget her repeating, “he brought that book.” (chuckles).

Katrina Schwartz: Her father returned to Oakland where his family was — and their home on Jones street was consumed by the fire. Elizabeth says the family was lucky to be able to stay with her grandparents in Oakland until her father purchased a plot of land in the Mission to build them a new house. She says many Black San Franciscans tapped into networks of friends and family in Oakland.

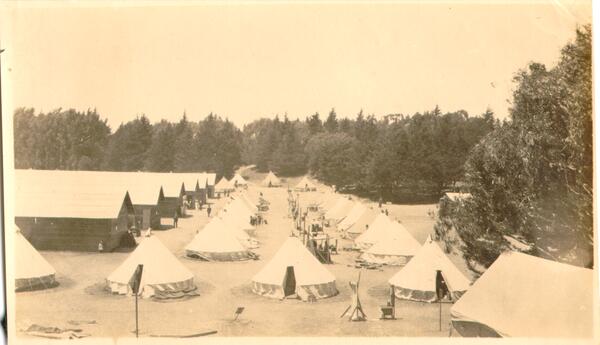

Elizabeth Fisher Gordon: The people from San Francisco came over here when their houses burned down and they took care of them over here. Red Cross, and they set up temporary housing and what have you for the people.

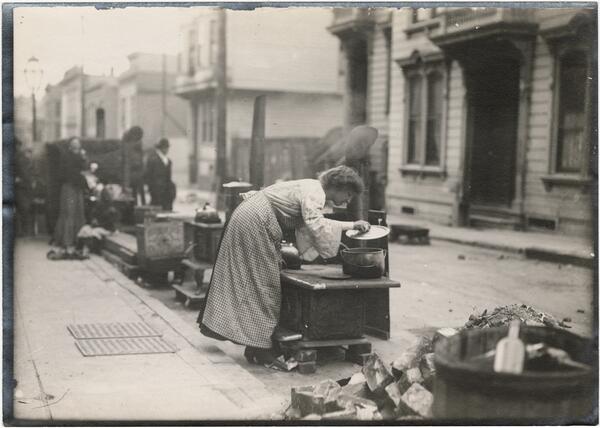

Katrina Schwartz: Tent cities sprang up in parks around San Francisco…housing 200-thousand people who had become homeless overnight. People set up outdoor kitchens and cooked together. Tanea lunsford lynx documented Black San Franciscans among these scenes in her exhibit.

tanea lunsford lynx: The first photo that we see is a photo of two young black people, children who are sitting in the grass and you see tents and you see a clothing line up behind them, and you see a little stove for cooking as well. And this is a campsite that was set up in Golden Gate Park, because folks had lost everything.

Katrina Schwartz: A PBS documentary called The Great 1906 San Francisco Earthquake paints a desolate picture of life in the aftermath.

The Great 1906 San Francisco Earthquake Narration: Standing in bread lines, meat lines, soup lines, any kind of a line became the central activity of life. Everyone had to do it. Soldiers made sure nobody cheated.

Katrina Schwartz: And anybody not standing in line, was put to work rebuilding the city.

The Great 1906 San Francisco Earthquake Narration: It was said that in many places, the debris was not even allowed to cool, and bricks were pitched from lots when still as warm as muffins. Volunteers on the cleanup crews took up the refrain in the damnedest, finest ruins I’d rather be a brick than live anywhere else but San Francisco. The great cleanup had begun. Thousands of standing walls were torn down. An estimated 6.5 billion bricks were carted away or cleaned of mortar to be reused in new buildings.

Katrina Schwartz: People who lived through these times remember it as a swift recovery. Alfred Butler was a Black teenager living in Oakland at the time of the earthquake. He took a mule and cart all the way down to San Jose and around the Bay in order to see what had happened to San Francisco for himself.

He recalls seeing a lot of rubble, and the biggest buildings knocked down. But over the following months the recovery progressed quickly.

Alfred Butler: They built it up right away. In a year’s time, things were pretty well cleaned up. And then they started to build.

Katrina Schwartz: At the turn of the 20th century, Black San Franciscans lived in neighborhoods scattered throughout San Francisco, but many single men were concentrated in hotels downtown…like Aurelius Alberga who we heard from earlier. Alfred Butler says after the earthquake, the Western Addition became the hub of Black life. That’s where his brother moved.

Alfred Butler: After the earthquake, everybody moved on Fillmore Street. All the businesses on Fillmore Street started booming.

Katrina Schwartz: San Franciscans came together after the quake and people from all walks of life helped one another in that moment of crises. But the oral histories of these Black Americans who survived it show that as the city rebuilt, it went back to the de facto racism that ruled it. Butler says good jobs were still reserved for white people, while Black people struggled to find menial ones.

Albert Butler: It was hard to get a job. Negroes, we had a tough time getting a job. A menial job like washing windows or running errands or something like that. Running an elevator or something like that. It was hard to get a job.

Music transition

Katrina Schwartz: For Tanea, the photos of San Franciscans living in tents, cooking outdoors, waiting in line for basic necessities are eerily similar to scenes on the streets of the city today.

tanea lunsford lynx: When looking at these photos, I began to see the past, speaking to the future and the future, speaking to the past.

Katrina Schwartz: And as a Black person, tanea sees echoes of her San Francisco in the oral histories she combed through. A small Black community fighting to stay in a changing city. The devastation of displacement and loss. But also the love of this place and the tenacity to survive. It’s all too familiar. Her poem “We Were Here” is an ode to the Black community in San Francisco, which stretches from the Gold Rush to now. Here’s an excerpt.

tanea lunsford lynx: We were here already, living fantastical lives, already saving the best for the present, already studying the contours of the city. The bay knew us. This ocean was salted with our knowing already. We knew the feeling of firm ground. Before the shaking. We knew stability. The ground knew the planting and rising of our feet like a dance. We were already sending for each other, extending a fishing hook south and pulling each other up with calloused hands. We were already spinning tales about this mass of fog. We were already making home here. (fades under)

Olivia Allen-Price: That story was brought to us by Bay Curious editor and producer, Katrina Schwartz.

tanea lunsford lynx: But of course, we were here, living in our signature ways. Of course, when the earth shifted, we went looking for who could be lost in the cracks. Of course it made for lore. Of course we were doing the fantastical feat like a dance. The earth cracked open and we kept time, an offering of our survival. We kept on living.

Music fades out

Olivia Allen-Price: tanea’s exhibit is no longer on display at the library, but you can see all the photos she used and read her writing on the project’s website. You can find a link in our show notes or on baycurious.org.

Special thanks to the San Francisco History Center, part of the San Francisco Public Library for letting us use the oral histories in their archive. And to the San Francisco African-American Historical and Cultural Society who co-sponsored the original oral history project.

There’s still time to vote in our April voting round. Here are your choices.

Voice 1: I was recently at the Morcom Rose Garden in Oakland and saw three different official Oakland signs that read, “No glitter.” I would love to know what happened at the rose garden to warrant so many signs.

Voice 2: Yesterday, I walked with a fellow science teacher on the Great Hwy. We commented on the blackish sand, made of iron filings. Where does the iron come from?

Voice 3: Who are the de Youngs? I think they have some crazy stories!

Olivia Allen-Price: Vote for which question you think we should tackle next at baycurious.org. While you’re there, sign up for our monthly newsletter, ask your own question, or get lost listening through the Bay Curious archive.

Bay Curious is made in San Francisco at member-supported KQED.

Olivia Allen-Price: Our show is made by:

Katrina Schwartz: Katrina Schwartz

Christopher Beale: Christopher Beale

Katherine Monahan: Katherine Monahan

Olivia Allen-Price: and me, Olivia Allen Price. Additional support from:

Jen Chien: Jen Chien

Katie Springer: Katie Springer

Cesar Saldana: Cesar Saldana

Maha Sanad: Maha Sanad

Holly Kernan: Holly Kernan

Crowd: And the whole KQED family.