Black student leaders and social justice icon Angela Y. Davis took the stage of a mostly full 1,800-seat auditorium at Alameda High School Friday night for a conversation on everything from joy in social movements and hair to reparations and racism. The Black Student Unions at Alameda High School and Castro Valley High School hosted the author and former UC Santa Cruz professor for a free, two-hour event.

“I’m so happy to be here,” Davis told the multigenerational crowd. Davis recalled how she used to ride past Alameda High School often when she was part of the Oakland Yellow Jackets Bicycle Club, but it was her first time being inside the building. “Thank you so much for inviting me,” she added.

Davis was invited to speak after Naomi Melak, a junior at Castro Valley High School and vice president of the school’s BSU, was inspired by seeing Davis’ appearance in the documentary 13th. She thought: “What if the BSU could put on an event with Davis?” Encouraged by her English teacher to pursue the idea seriously, Melak and her classmate, Diego De La Rosa Laday, president of the BSU, started a GoFundMe in November to raise $10,000 for Davis’ speaking fee through an agency.

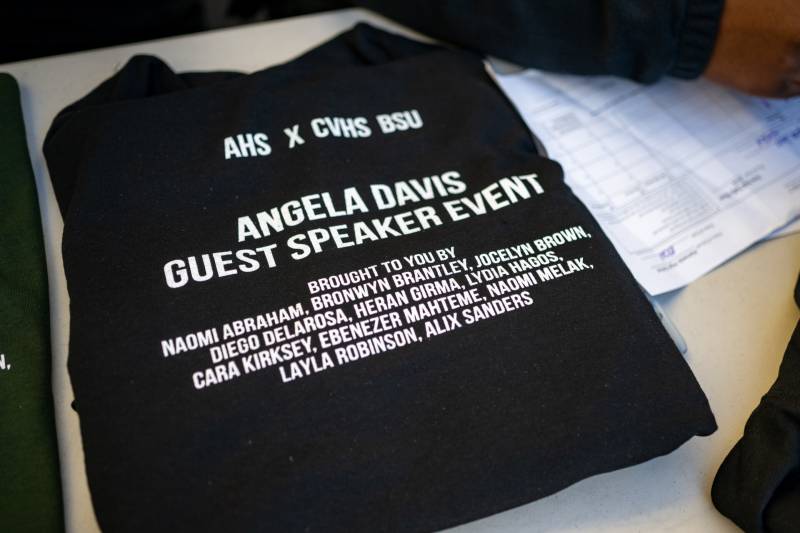

They sent it around to other East Bay high school BSUs, and students at Alameda High School’s BSU joined the effort to organize an event. The fundraising effort moved slowly, though. When the request eventually made its way to Davis in January, her scheduler relayed that she would do the event for free, and they could invest any funds they’d raised so far back into their BSUs.

Speaking to KQED prior to the event, student organizers said that they wanted to host Davis to help inspire change in their school communities, where hate speech and racist microaggressions towards Black students are an ongoing issue.

“It affects people mentally. It’s a continuous problem and a lack of response from teachers, as well,” said De La Rosa Laday. “We want someone [like Davis] who can inspire the community and who people can look up to, to build that courage to overcome these challenges and make change.”

For Naomi Abraham, a senior at Alameda High School and co-president of the BSU there, the event was a way to say that Black students on campus have a voice despite the racist incidents they’ve faced. “I want to leave a legacy at our school and show that it’s a place where Black students are just as much a part of the community as any other student,” Abraham said.

When the event got underway, Davis was introduced by Abraham and Melak. The two-part program with intermission saw a panel of four students, including Melak and De La Rosa Laday, take turns asking Davis questions on a range of topics.

Among the topics were Davis’ thoughts on her prison abolition activism, reparations, “I can’t think about reparations for Black people without thinking about reparations for Indigenous people” and reparations “should involve the transformation of the entire society”; the relationship between racism and capitalism; and education, “there is no liberation without education.”

Students also asked a pre-submitted audience question inquiring about her thoughts on the war in Gaza. “Don’t let anyone tell you that to be for the freedom of people in Palestine is equivalent to anti-Semitism. It is not,” Davis said.

The students mixed in some lighter points of conversation, as well — like when Alameda High School senior Heran Girma, who has curly hair, asked about Davis’ hair care routine. After an answer lasting a few minutes (that focused mainly on discussing the social mission behind her product of choice), Davis said, “This is the longest hair conversation I’ve had in public,” to laughter from the crowd.

One of the most rousing and poignant parts of the evening came when Alameda High School sophomore Bronwyn Brantley asked Davis about a pivotal moment in her early life that influenced her commitment to fighting for equality. Davis told the story of growing up in Birmingham, Alabama, living on the street that divided the Black neighborhood from the white neighborhood, which Black people were not allowed to cross unless they were going to work.

Davis recounted how she and other kids developed a game daring each other to run across the street and sometimes even ringing the doorbell of the house of a Ku Klux Klan leader who lived on the block and running away.