Episode Transcript

Sounds of birds, distant waves crashing, people talking, wind

Olivia Allen-Price (in scene): Wow. Okay, so I’ve been to this place a few times, but never on a day quite like today. It is a stunner out here.

Katrina Schwartz (in scene): Beautiful weather, perfect May day.

Olivia Allen-Price (in scene): Hey, everyone. Olivia Allen-Price here with Katrina Schwartz, producer extraordinaire of Bay Curious.

Katrina Schwartz (in scene): Hello.

Olivia Allen-Price (in scene): And we are at Sutro Baths. So right at the entrance of Land’s End, the hiking trail, if you’ve done that. We’re looking at the Cliff House to our left, a long-time-running restaurant, currently not running, but hopefully will come back again soon. But down in this cove is really why we are here. There is something pretty interesting down there.

Katrina Schwartz (in scene): It looks like a massive pool, except the edges of it are more like a pond with moss growing and ducks and seagulls. People are walking out on that retaining wall, but it has this air of mystery because you can tell something was once here, but now nature is reclaiming it.

Olivia Allen-Price: Today on Bay Curious, we’re going on a field trip to a spot many of you have been requesting over the years! We’ll learn why and how Sutro Baths were built, what visiting would have felt like back in the day, and while researching this story, we stumbled upon a lesser known piece of civil rights history — so we’ll be sharing that. This story first appeared in the Bay Curious book — available now wherever books are sold. We’re diving in — literally — just ahead on Bay Curious.

Olivia Allen-Price: San Francisco has a lot of historic places, many of which have been rebuilt or repurposed in modern ways. But the ruins of Sutro Baths remain wild and untouched. Bay Curious editor and producer Katrina Schwartz brings us the story of the rise and fall of this iconic bathing palace.

Katrina Schwartz: To understand why these somewhat sparse ruins have captivated the imaginations of locals and visitors alike, we need to learn a bit more about the man behind them. Adolph Sutro.

Hector Falero: He was born in Germany in 1830 to a Jewish family.

Katrina Schwartz: Hector Falero is a former education manager for the Golden Gate Recreation Area — the National Park that manages the Sutro Baths site now. He says Sutro arrived in San Francisco as a young man in 1850, right as the Gold Rush was kicking off.

Hector Falero: He’s living in San Francisco and mostly selling tobacco.

Katrina Schwartz: Many of his customers were miners, and he learned as much as he could about the business. When news of a massive silver discovery in Nevada hit the papers, he decided to join the fray and try to make his fortune on the Comstock Lode. He first opened a refining mill, but he’d long been thinking about one of mining’s biggest problems — surface water. It would seep down, sometimes drowning miners. Adolph Sutro’s solution was to build a huge tunnel deep in the mine that ran downhill and carried water away from the workmen. The Sutro Tunnel.

Hector Falero: He was able to eventually patent this and became kind of like a mythical figure among the silver miners in that part of Nevada.

Katrina Schwartz: Sutro made millions on his invention. He returned to San Francisco a rich man and began investing in real estate. He especially liked the wind-swept “Outside Lands” near the Pacific Ocean. Not many people lived out there yet, but Sutro wanted to change that. In 1881, he bought 22 acres of oceanfront property overlooking the Cliff House, which was already operating as an inn and restaurant. Sutro would buy the Cliff House just a few years later and incorporate it into his grand vision for the area.

Hector Falero: Where he saw a gap was in bathing or swimming.

Katrina Schwartz: In the late 1800s, most people lived crowded into boarding houses and rented rooms in downtown San Francisco. Saltwater swimming was all the rage, a welcome respite from these cramped interiors.

Hector Falero: There was some sort of like concept of health associated with Pacific waters. But it’s very cold. And so the need that Adolfo Sutro saw was, hey, I would love to create some baths and I would love to create them to be sort of temperature controlled.

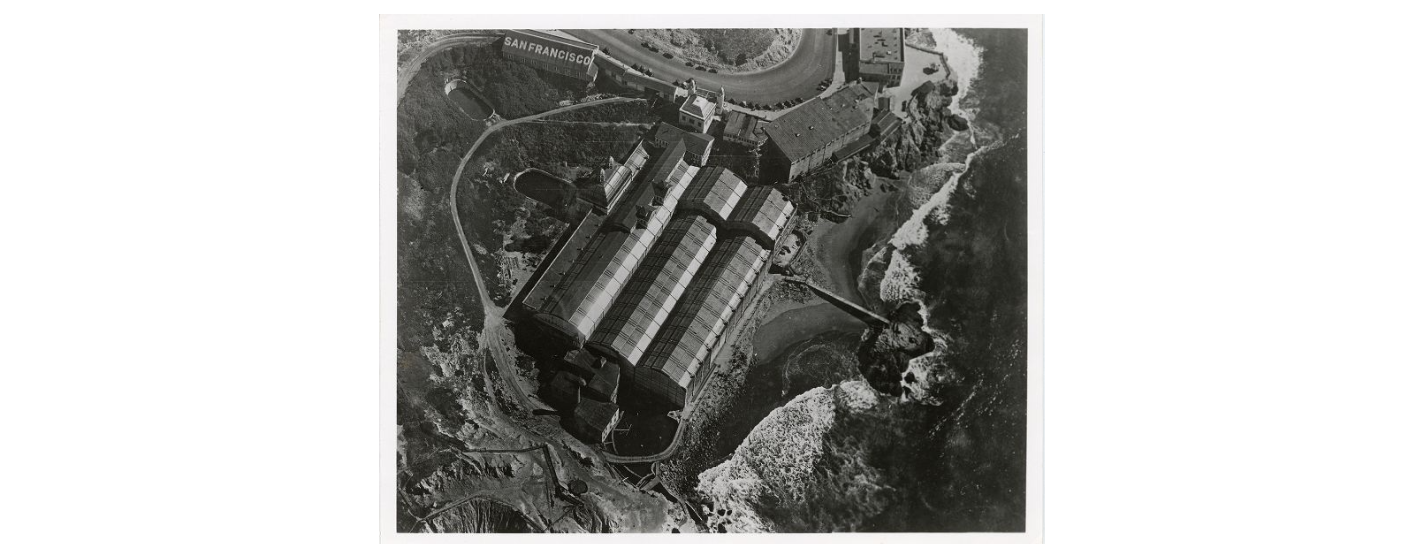

Katrina Schwartz: Sutro put his engineering brain to work designing a series of pools and tunnels that would harness the tides to create a swimming facility.

The first problem to solve was how to bring seawater into a protected pool away from crashing ocean waves. So, Sutro did what he did best. He built a massive tunnel.

Hector Falero: The water would rush in at high tide and be able to fill the pools almost instantly. This was one of the technological aspects that was incredible.

Katrina Schwartz: He demonstrated the system to reporters nearly a decade before the baths would officially open. An article in the San Francisco Chronicle reads:

Voice-over reads newspaper clipping: At great expense, a tunnel was excavated, 8 feet high and 15 feet long, through the solid rock. It is through this tunnel that the water comes at extreme high tide and for about two hours before and after.

Katrina Schwartz: Over the next many years, Sutro transformed this quiet cove into a massive engineering project. He built a seawall across the entire span to keep the waves out.

John Martini: He lined most of the cove with concrete.

Katrina Schwartz: John Martini is the author of Sutro’s Glass Palace: The Story of Sutro Baths. He presented his research to the San Francisco Historical Society.

John Martini: So he literally subdivided the cove into what he called swimming tanks. We’d call ‘em pools.

Katrina Schwartz: There were seven pools in all. Seawater would rush in through the tunnel and mix with extremely hot water coming out of a boiler house. Then, the rush of water would flow into the pools, each a different temperature.

John Martini: The warmest pool was about 85, 86 degrees, maybe up to 90. And then they were sequentially cooler until the biggest pool that was ocean temperature. They didn’t bother to heat it.

Katrina Schwartz: But that’s not all. Anyone who’s been out to Lands End knows how cold and windy it can be, so Sutro decided to build a huge glass pavilion to cover the pools.

John Martini: So, instead of an open-air swimming establishment, you ended up with the world’s largest indoor swimming complex.

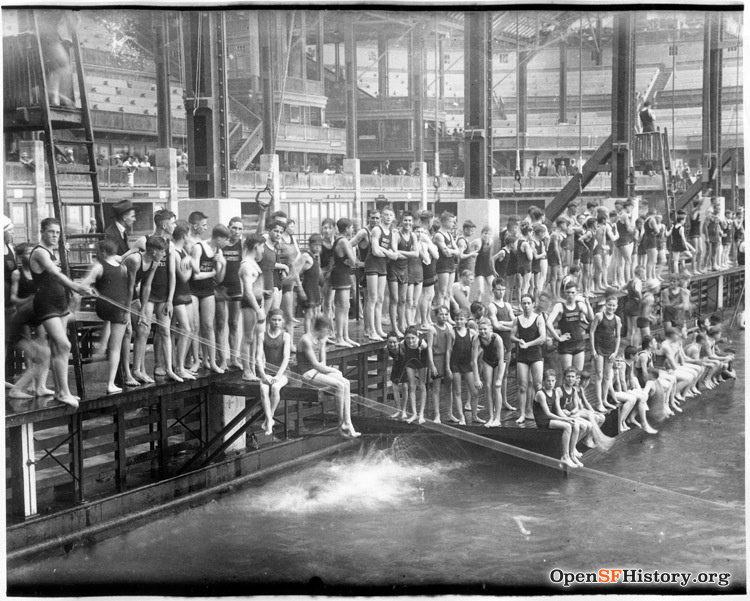

Katrina Schwartz: When it was finished, the baths had a footprint of 3 acres, about the same size as the ferry building — 10,000 people could pack inside.

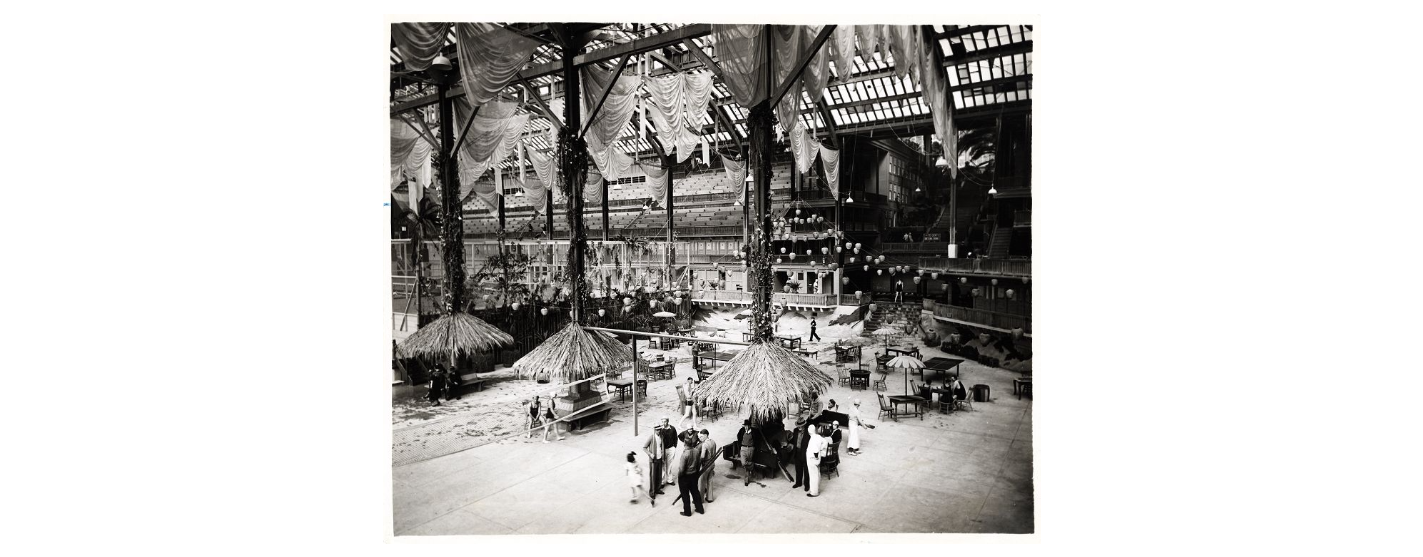

John Martini: People entered, and they descended a flight of stairs. The first level that you hit is called a promenade level, and the promenade level is where a lot of the museum displays were. You walked under a giant vestibule and then down a grand staircase that led you all the way down to the water on either side.

Katrina Schwartz: After more than a decade of construction, the baths formally opened in 1896. The San Francisco Examiner described the event.

Voice over reading newspaper excerpt: Nearly 7,000 people gathered at the immense pavilion yesterday to witness the dedication of the magnificent structure, which Adolph Sutro has built on his land near the ocean.

Katrina Schwartz: There were restaurants and bars, curiosities from around the world — like mummies and a stuffed polar — space for a large band to play, an amphitheater and lots of areas to promenade. It was a place to be seen.

John Martini: Those were colored panes of glass in the domes overhead so that sunlight gave multicolored, rippling effects on the water, especially when thousands and thousands of people at a time, making waves in the water, kids screams, music playing. It was an overwhelming sensation.

Katrina Schwartz: Sutro wanted the working classes to be able to enjoy a day at his leisure palace. … and to spend their money there. … so he pushed the railroads to keep the streetcar fares to Outside Lands low.

Hector Falero: He had this sort of egalitarian slant.

Katrina Schwartz: Hector Falero says his populist streak made him popular with the people. They even elected him mayor!

Hector Falero: He wanted people Of various class backgrounds to be able to access the place equitably.

Katrina Schwartz: For 25 cents, visitors could rent a bathing suit, use the lockers, visit the attractions, swim and stay all day. Advertising campaigns at the time said Sutro Baths welcomed ALL San Franciscans.

But that wasn’t actually true.

Somber music starts

Katrina Schwartz: One day, a group of friends took the streetcar from downtown out to enjoy a day at the new attraction. It was the fourth of July 1897, just a few months after the baths officially opened.

Elaine Ellnson: John Harris, who is an African American man, went with his several white friends to the baths.

Katrina Schwartz: Writer and historian Elaine Elinson researched this history for the National Park Service.

Elaine Elinson: He was a waiter in San Francisco, and he paid his $0.25. And his white friends got their bathing suits and went in the pools. And he was told he could not go into the pools. Only his white friends could go into the pools.

Katrina Schwartz: John Harris tried to enter the baths again a week later. Again, he was not allowed to swim because of the color of his skin. So, he sued the Sutro family.

Elaine Elinson: To challenge the former mayor of San Francisco really took a lot of chutzpah, bravado.

Katrina Schwartz: John Harris used a new California law called The Dibble Civil Rights Act to challenge his treatment at the baths. The law prohibited discrimination in public places based on race.

Susan Anderson: That all came out of black California.

Susan Anderson is the history curator for the California African American Museum.

Susan Anderson: It was significant to black people to have their rights enshrined. They worked together to influence Assembly Member Dibble to sponsor the Dibble Act, California’s first civil rights act, in 1896.

Katrina Schwartz: Many Black migrants to California were already skilled leaders in the abolitionist movement. Racist policies and attitudes limited them to low-paying jobs — hotel waiters, railroad porters, clerks — but through their work, they got to know powerful men like Dibble.

Susan Anderson: Enterprising people make the most of it. So, if you’re a porter or clerk in a court. And you’re an activist; you find comrades and allies and people you can network with people who are powerful for your cause.

Katrina Schwartz: Black activists likely wrote the Dibble Civil Rights Act and lobbied other legislators to pass it. Then, local groups like the African American Assembly in San Francisco tested the law, trying to give it teeth. That’s what John Harris did at Sutro Baths.

Elaine Elinson: We don’t have any exact testimony from John Harris himself.

Katrina Schwartz: Historian Elaine Elinson again. She says the court records burned in the 1906 fire. And mainstream newspapers of the day didn’t bother interviewing the central figure in the case, John Harris himself.

Elaine Ellinson: I have to say that the mainstream press was really vitriolic against John Harris and the judge.

Katrina Schwartz: Elaine pieced together her account from lawyers’ notes, newspaper articles and personal letters. She says the African American Assembly paid Harris’ legal fees.

Elaine Elinson: John Harris won his case, but, you know, he only earned $100 for the two times he was refused entrance to the baths. So it wasn’t a monetary victory, but it was a very, very important civil rights victory.

Katrina Schwartz: The Sutro family and Bath managers were unrepentant. They continued to make racist remarks that the mainstream newspapers published.

Elaine Elinson: It is interesting to see that these cases challenged and won but often did not change public attitudes or public policy.

Katrina Schwartz: Two years after Sutro Baths opened, Adolph Sutro died. He was 68. He left his estate and properties to his children, who continued to run the baths. And the attraction remained incredibly popular, but the Sutro family was ready to unload the property.

John Martini: They kept trying to sell it. No one wanted to buy it.

Katrina Schwartz: John Martini says Sutro sunk a lot of cash into constructing the baths, and they cost a fortune to run. His children wanted to recoup that investment.

John Martini: In 1913, the family tried to get the city to buy it. No dice. The city turned it down.

Katrina Schwartz: Then, in the ’30s, the Great Depression hit. Many San Franciscans didn’t have money for a leisure day at the baths, and slowly, the facilities began to fall into disrepair. Adolph Sutro’s grandson was in charge at the time.

John Martini: He decided to rebuild part of the baths and turn it into an indoor ice skating rink, and it opened in 1936 and it was immensely popular. Immediately popular.

Katrina Schwartz: John Martini remembers going there as a kid in the 1950s.

John Martini: The ice rink was actually quite dark inside. It turned out that all that great glass. It tended to melt the ice. So, they intentionally blanked out the glass roof over the ice skating rink.

Katrina Schwartz: In 1952, the Sutro family announced they were closing the facility. It just cost too much to run. That’s when one of their competitors, George Whitney, swooped in and bought it for a bargain. Whitney owned Playland-at-the-Beach, the popular amusement park on Ocean Beach.

John Martini: George Whitney revamped the baths one more time. He recognized that there was still a few nickels to be made out of the old place, and that he would be the perfect place for him to display all of his personal collections.

Katrina Schwartz: Antique carriages, historic photographs, pinball machines and other novelties that can now be found in the Musee Mecanique started out at Sutros.

John Martini: Much of what was in Sutro still exists. It’s just moved all over the world now.

Katrina Schwartz: Sutros finally closed for good in the 1960s. A San Francisco Examiner article marks the occasion:

Voice over reading newspaper excerpt: The second half of the 20th century at last caught up with an old San Francisco legend. Sutro Baths, created 70 years ago, closed forever.

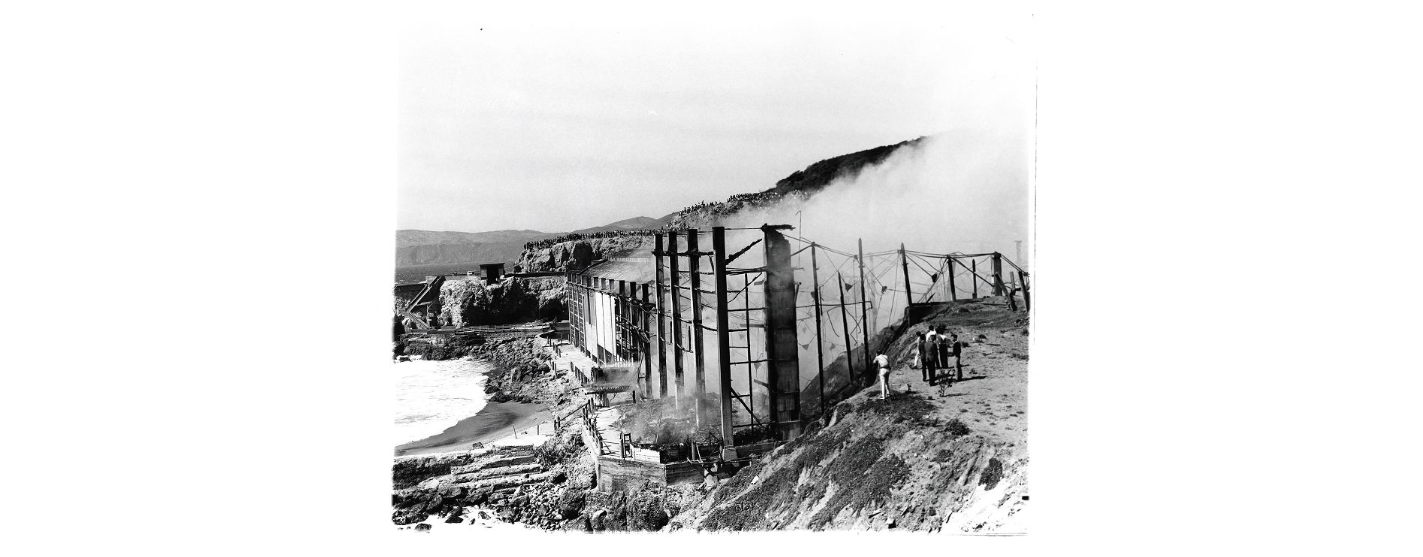

Katrina Schwartz: The Whitney family sold the Sutro Bath property to a developer who planned to build condominiums on the site.

John Martini: Demolition began in early June of 1966. And on June 26, 1966, a very convenient fire broke out that, in one long afternoon, destroyed the building.

Katrina Schwartz: Police suspected arson but could never prove it. In any case, the fire destroyed the building much faster than work crews ever could. People from the neighborhood came out to watch as the iconic white pavilion burned to the ground. Sutros creation up in smoke.

Sounds of waves, birds singing, the crunching of footsteps

Katrina Schwartz (in scene): Honestly, I can almost imagine what it looked like to Sutro when he came here.

Olivia Allen-Price (in scene): Yeah?

Katrina Schwartz (in scene): Yeah, like, with the beach out past the retaining wall and the big rock out there, you can almost imagine him, like, walking on the beach. More than 100 years ago.

Olivia Allen-Price (in scene): I mean, I can definitely understand how somebody would see this. And if you had the money to buy it, think this must be mine! Once you kind of get down closer to the baths, as you look up, you can really get a sense of where the rest of the building used to be. If you look up at the hillside that’s kind of underneath the Cliff house, there’s a number of just like slabs of concrete that probably indicate different levels of what was once here.

Katrina Schwartz (in scene): Clearly man-made.

Olivia Allen-Price (in scene): Yeah. All right. So we’ve made it down to the ruins, and we’re standing on the retaining wall. That really is a wall between two worlds. On one side, we have the wild Pacific battering the coastline. And on the other side of the wall, the world that Sutro built, which these days looks more like a home for the birds.

Katrina Schwartz (in scene): Yeah, this may be a swimming hole for the birds now, but standing here on the wall, you could almost imagine diving in, back in the 1920s, in your really heavy bathing suit, with a slide.

Olivia Allen-Price (in scene): And how majestic it would have been to be able to swim and also look at the ocean at the same time. But it was a complicated story. This wasn’t an amazing space for everyone.

Katrina Schwartz (in scene): Right. It’s got a nostalgic element to it for some people, a lot of happy memories. But for other people, this place is a symbol of pain and rejection.

Olivia Allen-Price (in scene): Now I can’t help but notice. But there are not condominiums here, as was once the plan. What happened with that?

Katrina Schwartz (in scene): Well, so after the fire, the property kind of just languished for about a decade. Then, the National Park Service bought it, and they turned it into open space. And they asked San Franciscans what they wanted done with the new park. And people basically said they wanted to leave it as it was — ruins. Something that they could explore on their own terms, not interpreted with any park signs or pathways or anything like that. Just a place you could explore, which is what we’re doing right now.

Olivia Allen-Price (in scene): In a way, that’s really the most perfect ending for this story, because it’s still an attraction people come to for its beauty, for the experience of being here. But now it’s a truly public space that’s free and open for everyone.

Music starts

This episode of Bay Curious was made by…

Katrina Schwartz (in scene): Katrina Schwartz

Olivia Allen-Price (in scene): Our engineer, Christopher Beale, and me, Olivia Ellen Price. Extra special thanks to our field recording team this week…

Tamuna Chkareuli (in scene): Tamuna Chkareuli

Lusen Mendel (in scene): Lusen Mendel

Katrina Schwartz (in scene): Katrina Schwartz

Olivia Allen-Price (in scene): And me, Olivia Allen-Price. We had a blast at Sutro Baths. If you haven’t been, go check it out.

Bay Curious is made in San Francisco at member-supported KQED. Lots of folks to thank this week, including the San Francisco Historical Society, for letting us use John Martini’s presentation. The people behind this podcast include:

Jen Chien: Jen Chien

Cesar Saldaña: Cesar Saldaña

Katie Sprenger: Katie Sprenger

Maha Sanad: Maha Sanad

Holly Kernan: Holly Kernan

Crowd: And the whole KQED family.