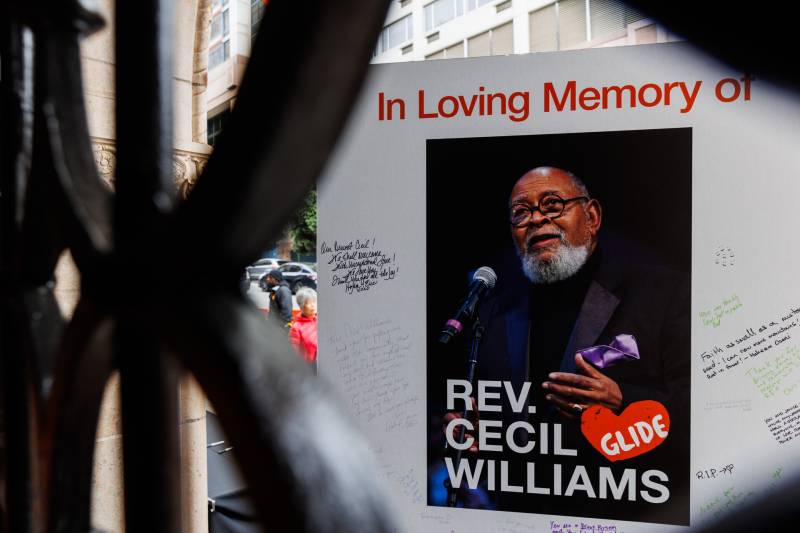

Friends, elected officials and ordinary San Franciscans who benefited from his decades of ministering to the poor filled the sanctuary of Glide Memorial Church in the Tenderloin on Sunday afternoon to celebrate the life of Reverend Cecil Williams, who died last month at the age of 94.

Classy Martin, a Glide member since childhood, recalled how Williams was like a foster father to her. “I met so many amazing people through Cecil,” she said; he helped show her she didn’t need to be on the streets.

Marvin K. White, who is now Glide’s senior pastor, recalls that under Williams’ leadership, Glide became a community anchor, “He was here all hours of the night. He would stand outside. He would greet people,” White said.

Williams was known as a champion of racial equality, LGBTQ rights, and San Francisco’s most impoverished residents. His death on April 22 brought an outpouring of tributes from a wide range of the city’s official family, including this statement from Vice President Kamala Harris.

“Reverend Cecil Williams was a beacon of light and love,” said Harris, who worked with Williams when she was San Francisco District Attorney.

“In all he did, Reverend Williams was guided by his faith. He fought for the rights and dignity of all people. Cecil offered every person who walked through his doors a warm smile, a hot meal, and unconditional love,” she added.

Albert Cecil Williams was born in the West Texas town of San Angelo in 1929. The grandson of slaves, Williams told NPR’s Michele Martin in 2013 that his mother decided early on that he would be a pastor when he grew up.

“So they called me ‘Rev’ when I was 2 years old and when I was 6 years old,” he said. “It was ‘Rev, Rev, Rev.’ So here I am. You know, here’s the reverend,” Williams said.

After graduating with a degree in theology from Southern Methodist University in Dallas, Rev. Williams was recruited by the United Methodist Church in San Francisco — then a very small and dying house of worship whose members were all white.

After attending the 1963 March on Washington, D.C., where Martin Luther King Jr. gave his iconic “I Have a Dream” speech, Williams arrived in San Francisco. It was a more conservative time — the city had a Republican mayor, George Christopher — and the San Francisco police routinely arrested people at gay bars.

Williams quickly decided that to be relevant in the turbulent 1960s, Glide needed a different approach, which he described in an interview with the local CBS television station in 1971.

“I believe that we have to radicalize things to get things done very quickly. Also, I believe that Jesus Christ was a revolutionary and he was a radical,” Williams said. Emphasizing Glide’s embrace of second chances, he said, “People tell me, this is the first time that we’ve come to church and felt good. Most churches people go to feel guilty. I don’t know why churches want to make people feel guilty. We work out our problems together, you see,” he said.

Indeed, Williams opened the doors of Glide Church to anyone and everyone. Cleve Jones, who left Arizona as a teenager and landed on the streets of San Francisco in the 1970s, remembers Williams’ ministry in the Tenderloin as a very welcoming place.

“Glide Church was one of the few places where young gay kids like myself could go get a meal, get some counseling, get some help. He was a real pioneer.”

Jones, who later became a leading advocate for LGBTQ causes, remembers Williams as a critical bridge between the Black clergy and the city’s growing queer-identified residents.

“He had this ability to bring folks together in a way that reduced tension and also opened doors for funding and support for really critically needed services. He was a master at it,” Jones said.

Randy Shaw, a longtime housing advocate in the Tenderloin, noted that Rev. Williams was never afraid to raise his voice for people who lacked powerful advocates.

“He was the fiery minister who was urging people to get involved in stuff and fighting for justice and not mincing words about things. He was very outspoken,” Shaw said.

As Glide’s membership grew, Williams expanded his ministry to include things like free meals, legal services and health and wellness clinics. And, Shaw notes, he raised millions of dollars to keep it afloat.

“Cecil was able to make financial connections to donors no one else in the Tenderloin, and maybe even in San Francisco, could make. He was the one who the big donors would give to,” he said.

In 2012, Williams told KQED that Glide tapped into what people were looking for in their lives — authenticity and meaning.

“People want something that matters, and what really matters is a radical love. Taking risk — what we call ‘having courage,’” Williams said.

Indeed, hundreds of people regularly lined up outside Glide for Sunday services. Inside, congregants of every race, gender and sexual orientation, socio-economic status and background locked arms in celebration — treated to a rollicking service that never disappointed.

Over the years, Glide has become a San Francisco institution. Its music ensemble performs at weddings, mayoral inaugurations and funerals — spreading its message of love, diversity, healing and second chances. He became a quintessential political insider, having the ears of mayors, city supervisors and members of Congress.

House Speaker Emerita Nancy Pelosi called Williams “a spiritual giant whose saintly good works have transformed countless lives in the Bay Area and beyond.”

She added that “Reverend Williams was a clarion voice for love and justice: whether fighting against racism, protesting the Vietnam War, addressing poverty and addiction, and so much more.”

Rev. Williams officially stepped down as CEO of the Glide Foundation but took up the title “Minister of Liberation.” He would still offer sermons from time to time, even when he was in a wheelchair.

As his health began to fail him, Williams gradually stepped away from the job.

“I was working here at Glide, and I got a chance to see him up close and personal and see how he put his body on the line, how he lived liberation,” Pastor White said.

White knows he can never replace Cecil Williams — but he said he learned a lot from him. “I have lost a brother, a mentor, a brilliant theologian, a great role model for what it means to be a Black prophetic preacher and minister.”

KQED’s Christopher Alam, Azul Dahlstrom-Eckman and Spencer Whitney contributed to this story.