The WastewaterSCAN project has found evidence of bird flu at more than a dozen locations, including two states — Minnesota and Iowa — that officials have yet to list as having infected herds. Last week, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention announced the third human case of bird flu was reported in a farmworker in Michigan who experienced respiratory symptoms after exposure to an infected herd.

No human cases have been reported in San Francisco or elsewhere in California.

A more precise wastewater measurement

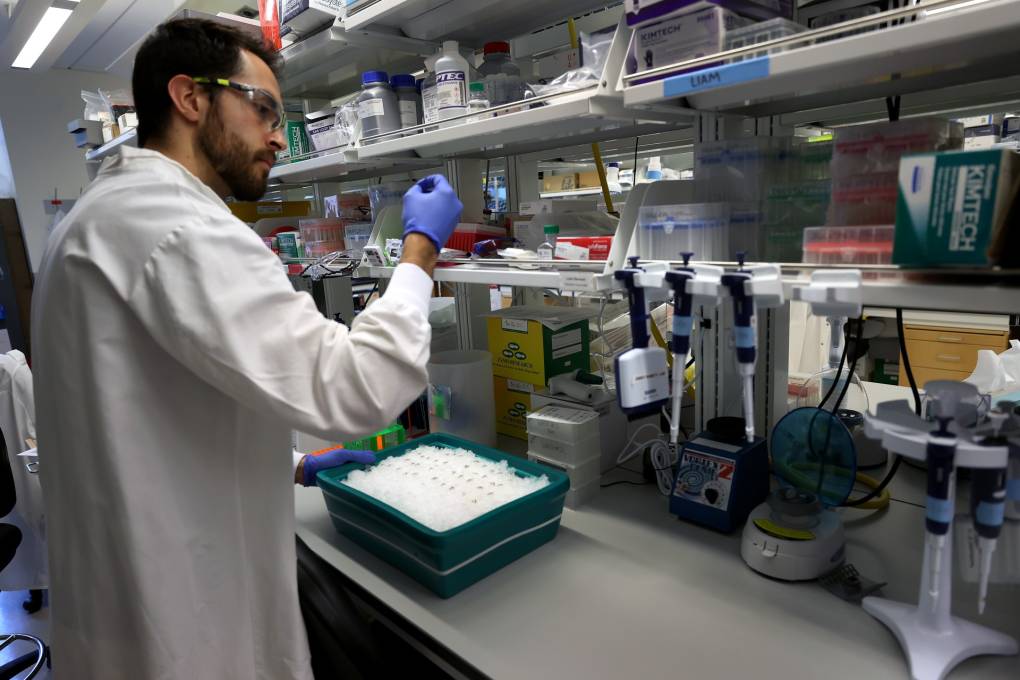

The work by Boehm’s team represents the first time researchers have tested for H5N1 in wastewater.

It builds on a pandemic-era playbook for monitoring wastewater for COVID-19, which has since expanded to other diseases, even the use of illicit substances and drugs.

Although the CDC has tracked influenza A viruses in sewage — using them as a barometer for the spread of bird flu because flu viruses that sicken humans circulate at low levels during summer months, that testing is not H5N1-specific.

Boehm’s team, working with San Francisco and California health officials, developed a precise marker for H5N1 bird flu last month as dairy cow outbreaks spread across the U.S.

“Once we had the detection in the live bird market, that was an opportunity to look at wastewater for H5N1,” said Dr. George Han, director of the San Francisco Department of Public Health’s communicable disease prevention and control program.

Although researchers found fragments of bird flu material in the frozen bank of sewage from San Francisco, subsequent monitoring detected no further evidence in the city “nor elsewhere in California, for that matter,” Han said.

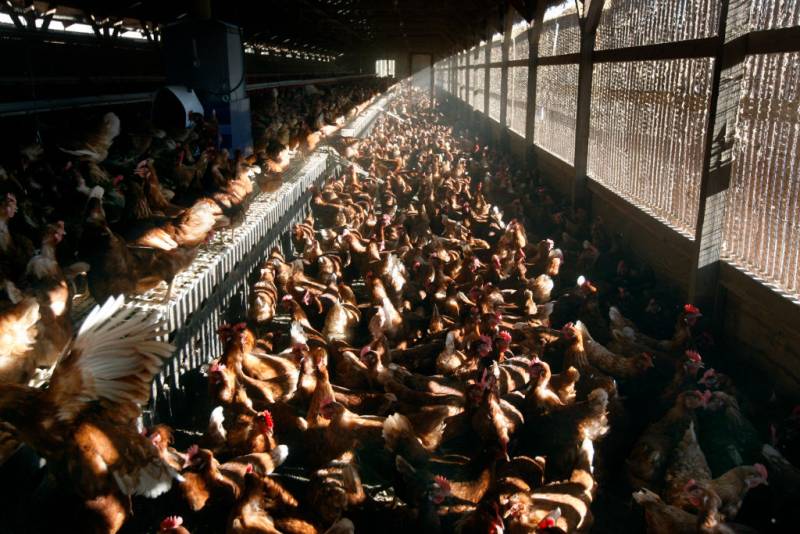

That’s potentially good news for the state, which boasts the largest dairy industry in the country with more than 1.5 million dairy cows. Federal officials had observed several jumps in influenza A viruses in California, which they thought could indicate that bird flu was circulating across its ranches.

San Francisco’s health department does not believe that any of the wastewater hits for bird flu are related to human infection, Han said.

“I think that’s really important and the take home message,” he said. “No one really thinks at this point that the detections are due to human cases of H5N1.”

San Francisco’s unique sewer system

San Francisco is one of only about 700 American communities with a combined sewer system, with stormwater and sewage flowing through the same pipes.

That’s an issue for the city during bad storms when the system regularly overflows — the city is fending off a lawsuit from federal and state environmental officials for discharging billions of gallons of untreated sewage into the San Francisco Bay each year because of it. However, it is a benefit for this disease research work.

San Francisco’s health department has a working hypothesis: Migratory birds with avian flu may have passed through San Francisco, and their waste ended up in its combined sewer shed.

“If there is any kind of bird feces in the street and somebody washes it off the street or the sidewalk, that material ends up in the sanitary sewer,” Boehm said. “We’re able to use that wastewater to understand circulation of both human disease, but also, in some cases, animal disease.”

That, Boehm said, could help scientists “better understand the extent and duration of the H5N1 outbreak this spring in the United States.”