Episode Transcript

This is a computer-generated transcript. While our team has reviewed it, there may be errors.

Olivia Allen-Price: On the western edge of San Francisco, just south of San Francisco State and Parkmerced, you’ll find a street with the curious name … Brotherhood Way.

The wide boulevard has a grassy median with mature trees, but what really makes Brotherhood Way stand out is its residents. Large buildings featuring the Star of David, an Eastern Orthodox cross and a crucifix — all in a row.

Noor Moughamian: [speaking in Armenian] It means my name is Noor; what’s your name?

Olivia Allen-Price: Noor Moughamian is a 5th grader at the KZV Armenian School, also on Brotherhood Way. They learn in both Armenian and English at her school, and just up the road is a Jewish school and a Catholic school, as well as several houses of worship from different faiths.

Noor Moughamian: I feel like it’s like kind of family, like, community, I feel like?

Olivia Allen-Price: The schools plan activities together sometimes, and Noor says there’s a feeling of … brotherhood … just like the name. Across the street from the Armenian school, there’s even a little statue.

Noor Moughamian: [Reading] Dedicated to the brotherhood of man and the ideal and the ideal of peace among all the peoples of the world.

Olivia Allen-Price: Brotherhood seems to be everywhere, and Noor wants to know if that was always the plan.

Noor Moughamian: I was just wondering if like, were the churches built onto the name of the street? Or was it? Or did they come up with the name and then decide to build churches and schools?

Bay Curious theme music starts

Olivia Allen-Price: How did this quiet corner of San Francisco come to be home to so many religious communities? And which came first — Brotherhood Way or the institutions on it? Today’s question was selected by you, our podcast listeners in our monthly public voting round. It comes from Noor, who is 11 years old, but to answer it, we get to chat with one source who is 102! That’s all just ahead on Bay Curious, the show that answers your questions about the San Francisco Bay Area.

I’m Olivia Allen-Price. Stay with us.

Olivia Allen-Price: KQED Reporter Katherine Monahan set out to Brotherhood Way to check out the houses of worship and find the answer to Noor’s question.

Sounds of chanting

Katherine Monahan: In the Holy Trinity Greek Orthodox Church, blue light shines from the stained glass windows and glitters on the gold-painted walls. The parishioners, in suits and dresses, are lining up to receive communion wine from a long, slim spoon.

It all feels suffused with a solemn glory.

More chanting

Katherine Monahan: This church has been around for over a century. And so has one of its members.

Ethel Davies: I’m Ethel Davies, and I’m 102.

Katherine Monahan: Davies lives nearby. She answers the door in a navy blue suit, pearls and red lipstick. She doesn’t plan on slowing down anytime soon, so I had to ask: what’s the secret?

Ethel Davies: So many people, even my doctor ask me that one. I was a walker. I walked every street in San Francisco.

Katherine Monahan: Davies says her family came from Greece in the early 1900s and settled south of Market.

Katherine Monahan (in tape): And were there a lot of Greek Orthodox people in San Francisco at that time?

Ethel Davies: There were, there were. Yes. South of Market had Irish and Greek people. It was their neighborhood.

Katherine Monahan: Greektown, as it was called, had traditional coffeehouses and restaurants and a Greek language school. And that was where the Holy Trinity Greek Orthodox Church church used to be.

Ethel Davies: In fact, it was on 7th Street in San Francisco at one time. And today, that is a Ukrainian Orthodox church. And that’s where I was christened when I was an infant.

Katherine Monahan: Davies isn’t just a super impressive centenarian. She had a front-row seat to the development of Brotherhood Way because her brother, George Christopher, was the mayor largely responsible for it.

Ethel Davies: I had a total of two brothers and two sisters, and I was the youngest in the family.

Katherine Monahan (in tape): And where was George in there?

Ethel Davies: Number one.

Katherine Monahan: He was born back in Greece as George Christopheles but later changed the name to Christopher. When he was 14, their father became sick. So George dropped out of school and went to work.

Ethel Davies: My brother? He took over when my father died, and he made a good life for us. Yes, yes.

Katherine Monahan: George Christopher went into the milk business and worked his way into the middle class, like many of his fellow Greek immigrants. In the 30s, many Greek families and businesses moved away from Greektown to other neighborhoods. The Christopher family moved out to the southwest side of San Francisco near Lake Merced.

Music starts

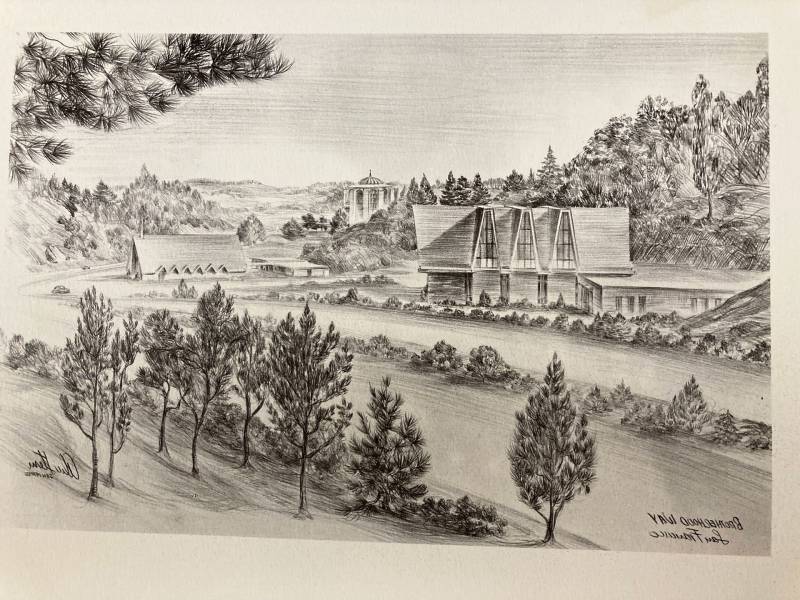

At the time, the area was still pretty undeveloped. What would later become Brotherhood Way was a forested canyon with a creek running into Lake Merced. Then, men employed by the New Deal built a road along it called Stanley Drive. It was straight and long and pretty isolated, so for a while, it was a popular drag racing spot for teenagers. At least one car ended up in the lake.

Music stops

Davies remembers when her brother had the idea to turn that road into a community space.

Ethel Davies: He wanted it to be a church area where all the different churches could meet and be friendly.

Katherine Monahan (in tape): I assume that he had a relationship with the pastor of the Greek church especially?

Ethel Davies: Father Anthony. Yes, yes. He was a wonderful man.

Katherine Monahan: So after George Christopher became the mayor of San Francisco in 1956, he arranged an auction of the city-owned lands along Stanley Drive. The biggest parcel went to the Holy Trinity Greek Orthodox Church — his church — which was outgrowing its building south of Market. The rest of the properties went to other religious and community institutions.

Ethel Davies: It really makes friends of the various religions, which they’re all the same. We all believe in one thing, you know.

Katherine Monahan: The faith institutions petitioned the city to change the name of their new address. And in 1958, Stanley Drive became Brotherhood Way.

Ethel Davies: And I think that Brotherhood Way is a wonderful name anyway, don’t you? Brotherhood Way, yeah. I remember when Father Anthony and my brother celebrated when they came across that name. They were so happy.

Katherine Monahan: So the places of worship did come first, and the name followed.

Music starts

And now, Davies is stepping out for the evening.

Ethel Davies: Oh, I’m going to the yacht club with friends for dinner.

Katherine Monahan: As Davies heads off to her busy social life, I head back to Brotherhood Way to meet another elder, Judge Quentin Kopp.

Music stops

Quentin Kopp: I’m a retired San Mateo County Superior Court judge. And before that, I was a California state senator.

Katherine Monahan: Kopp was also on the San Francisco Board of Supervisors, and he knew George Christopher through politics. He meets me in front of the Jewish synagogue.

Quentin Kopp: The building has been here since about 1963.

Katherine Monahan: It’s tall and angular, with peaked red and blue stained glass windows. Kopp and his family have been coming here for six decades.

Quentin Kopp: In 1964, the first of three children was born. A boy.

Katherine Monahan: Of the original five buildings constructed on Brotherhood Way, four of them were houses of worship.

Katherine Monahan (in tape): It seemed like religious institution, religious institution, religious institution and then the masonic temple, which, in my understanding, is not specifically religious. How does that fit in?

Quentin Kopp: Masonry was popular. There was more than one lodge in San Francisco.

Katherine Monahan: Masonry is certainly a brotherhood — no women are allowed. It’s a worldwide secretive society that, while not religious, promotes fellowship and community service.

Quentin Kopp: Masonry was strong. And, I think that is the origin of giving that property to the Masons.

Katherine Monahan: Over the years, Brotherhood Way has evolved to reflect people’s changing beliefs and affiliations. The original properties have been subdivided and new institutions have appeared.

The Masonic lodge now rents space to two bridge clubs and a Christian church. Several community centers have opened on the street and an Armenian church,

Babbling sounds of people talking and kids playing

One of the most recent additions is a non-denominational Christian congregation called New North Church, where the Sunday service has just gotten out. Kids are running around out front, dodging between tables of coffee and pastries.

Rob Hall: We’re like the new kid on the block. So we’re getting to know our neighbors more.

Katherine Monahan: Pastor Rob Hall invites me inside the church, which is shaped like a giant triangle.

Rob Hall: We know the Armenian Church. We know the the Jewish synagogue. And then we’re also getting to know all the RVs down on Lake Merced. And we, we, we do kind of an outreach where we bring coffee.

Katherine Monahan: Hall says it’s all about being neighborly and that he likes being near the other faith institutions on the street.

Rob Hall: We may believe different doctrines and have different beliefs and core tenets, but my experience has been that we help each other because, you know, San Francisco is not an easy place to be a person of faith, no matter what your faith background is.

Katherine Monahan: Hall says people in San Francisco don’t go to church as much as they used to. A lot of his parishioners come from the peninsula.

Rob Hall: We have a lot of different ethnicities represented here and then we’re also multi-generational. So we have a lot of young families with kids.

Music starts

Katherine Monahan: I called Noor, our question-asker, to see what she thinks about what I found.

Noor Moughamian: I mean, I guess I kind of thought that the street came after everything.

Katherine Monahan (in tape): Yeah. I remember you saying at the beginning. So you were right. You were right.

Katherine Monahan: So, she wasn’t very surprised that the churches came first and then the name Brotherhood Way. But she liked learning about the Christopher family.

Noor Moughamian: When the brother stepped in when the father died, I thought that was pretty cool.

Katherine Monahan: And she said the story made her think about her school a little differently.

Noor Moughamian: It kind of shows that like all the other churches and like school, I guess it kind of shows that everyone on Brotherhood Way is more like a community.

Olivia Allen-Price: That story was brought to us by KQED’s Katherine Monahan.

The June voting round is up at BayCurious.org. If you haven’t cast your vote yet, mosey on over to check out the options.

Voice 1: I want to know more about earthquake cottages in SF. Are there any still around?

Voice 2: What you tell me about Brooks Island, the little sister to Angel Island in the San Francisco Bay? Are hikers allowed? Is there any way to get out there?

Voice 3: What is the San Francisco Columbarium? I read that once, maybe while it was being restored, people’s remains were stored in the basement of the Coliseum theater on Clement.

Noor Moughamian: Bay Curious is made in San Francisco at member-supported KQED.

Katrina Schwartz: This episode was edited by Katrina Schwartz.

Christopher Beale: Produced by me, Christopher Beale.

Olivia Allen-Price: And me, Olivia Allen-Price.

Xorje Olivares: Additional support from Xorje Olivares…

Everyone saying their own names: … Tamuna Chkareuli, Bianca Taylor, Jen Chien, Katie Sprenger, Cesar Saldana, Maha Sanad, Xorje Olivares, Holly Kernan …

Olivia Allen-Price: And the whole KQED family. If you’ve been enjoying Bay Curious, please leave us a rating or a review. They help other people find our show, and honestly, they make our reporters feel super good about the work they’re doing. Thanks so much.