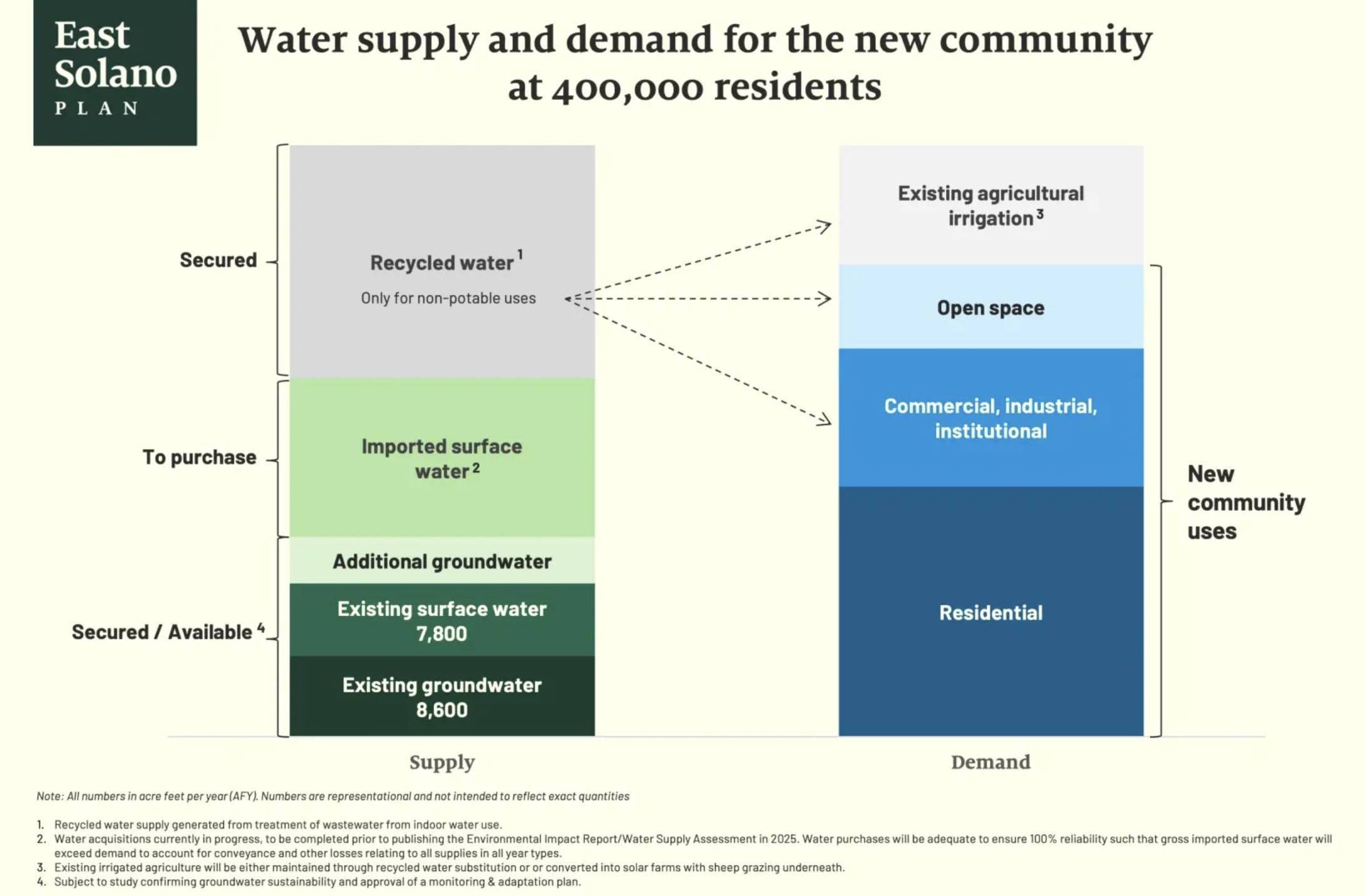

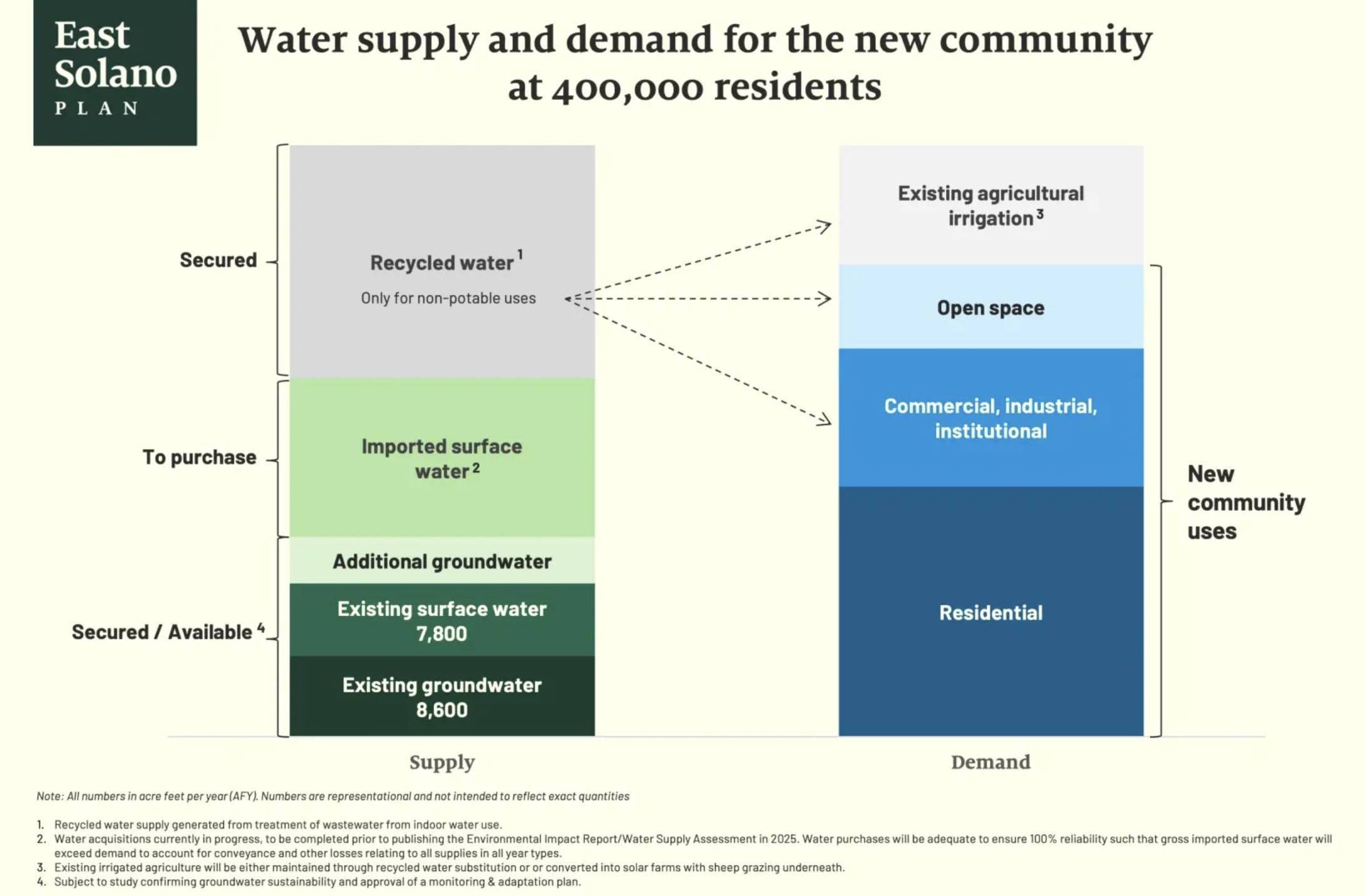

California Forever representatives said they also plan to import almost a third of their water supply “upriver from out-of-county sites in California,” conveying it through “existing points of diversion on the Sacramento River and its associated tributaries.”

Water experts who have reviewed California Forever’s plan said it’s clear the company did its homework, but some vital questions remain — especially around its plan to rely on water diverted from rivers in a state where drought is so commonplace.

“I am impressed that California Forever has engaged water resource management and legal experts to evaluate the complex issues that are raised by the proposed city,” Brian Gray, a senior fellow at the Public Policy Institute of California’s Water Policy Center, said to KQED. “However, the projected short- and long-term water supplies will be tight, and there are many details that remain unresolved.”

While Gray said it’s not uncommon for California cities to import water to serve their residents, he noted how precarious it might be for California Forever to rely so heavily on that amount of imported water.

“The way they’re describing their imported water strategy suggests that the long-term water supplies are tenuous,” Gray said. “I’m not saying it’s impossible, but I think there’s a lot of red flags.”

Gray also questioned where the company could import enough surface water to make up a third of the new city’s total supply, especially because California Forever has stated it will not seek water from Lake Berryessa via Solano County’s irrigation district. They have not identified precisely any other long-term water supply source.

Company representatives said they are in “advanced talkes on numerous aquisitions” and the details will be ironed out before it releases an environmental impact report.

“It can’t be some loose thing in the future that we’ll acquire what we need, we actually have to have the control of that water,” he said. “We’ll acquire some amount greater than what we actually need for resilience in drought years.”

Gray noted that water acquired from existing users in the Sacramento River basin would have to be conveyed through the California Department of Water Resources’ North Bay Aqueduct, which is currently “oversubscribed” by other cities.

In addition to importing water, California Forever plans to pump groundwater from the Fairfield-Suisun and Solano Subbasins, whose 60,000-acre property sits atop. A concern there, Gray said, is that the basins could become overdrafted, like many others, over years of drought.

So much water has been pumped from the Solano subbasin that the state’s Department of Water Resources has required local agencies to limit the amount of water landowners can use from the ground in times of drought.

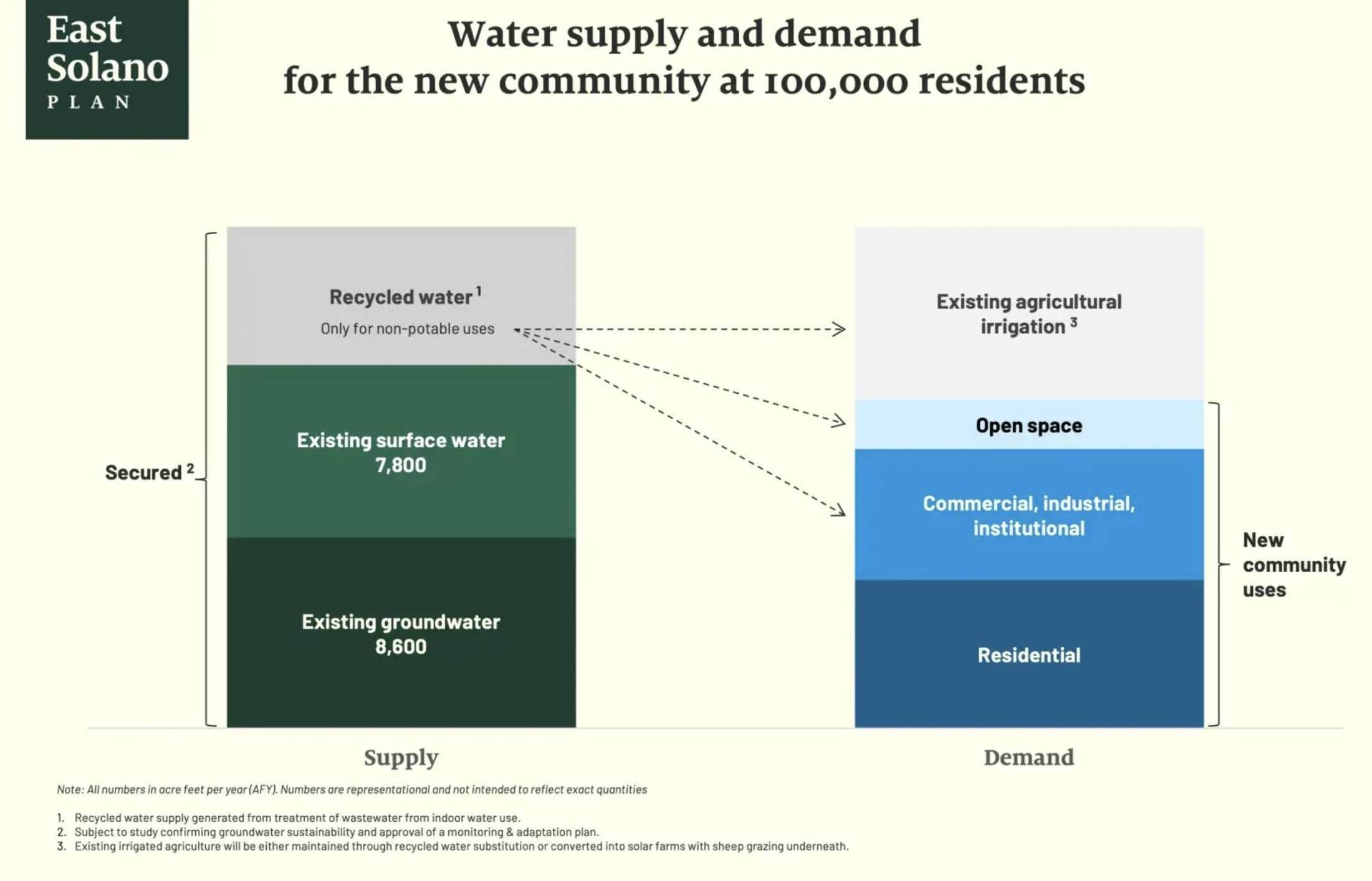

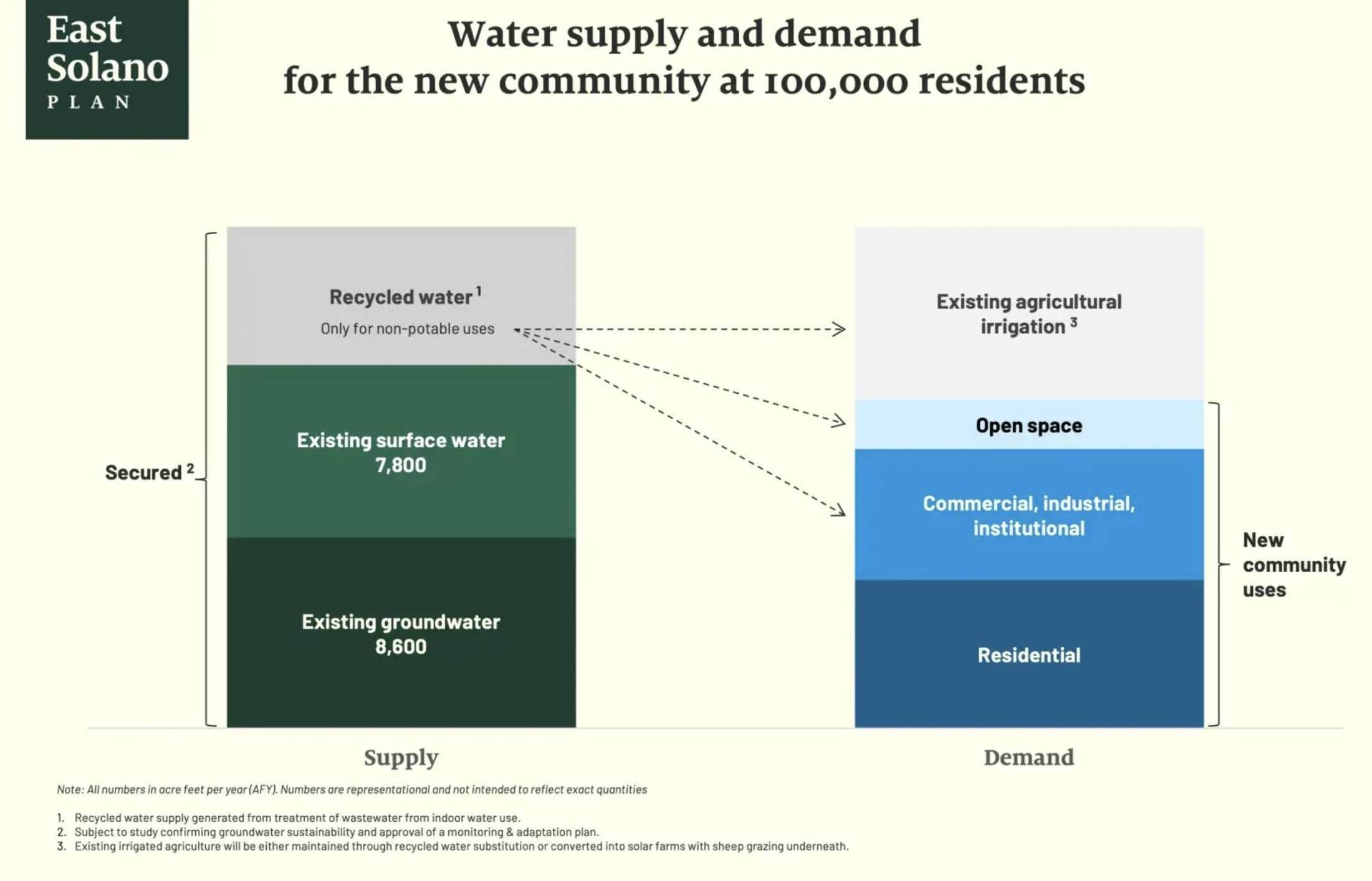

The biggest percentage of the new city’s water supply — about 40% — will come from what the company calls a “circular economy” of recycled water powered by water and wastewater treatment plants to be built in the new city. The recycled water won’t be used for drinking, cooking, laundry or other household uses, but instead will be put to agricultural, industrial, commercial and other uses.

“We’re focusing on that lower-hanging fruit,” Johnson said. “We can design those plants so that we’re able to move that recycled water where it is best used and then maintain those precious potable water supplies.”

California Forever argued its new city won’t require as much water as other, more suburban cities because it will be dense by design and will not have room for lush, green lawns and sprawling golf courses. Its residents will only use 60 gallons of water per day, far less than other cities in Solano County, which average about 100 gallons each day. For reference, San Francisco residents use up to 42 gallons per day, while Sacramento uses about 152 gallons per day.

Some experts noticed similarities between California Forever’s water plan and those of other cities that are now amending their water plans to withstand drought. David Sedlak, director of Berkeley’s Water Center, said the use of recycled water to irrigate landscape and agriculture “is a very well-established approach in California.”