S

itting on stage with her harp resting in her lap, Destiny Muhammad repeats this mantra: “Excellence, Beauty, and Success.” It’s part mic-check and part pump-up.

When she first started learning to play the harp, the Oakland-based composer and musician used to suffer from stage fright. Now, more than 30 years later, she commands the stage with a presence fit for a woman who calls herself the “sound sculptress.”

Her acclaimed career has been peppered with awards and honors, including Governor of the Board for the SF Chapter of the Recording Academy and California Arts Council Legacy Fellow. But before she was any of this, she was a self-described “shorty in Compton,” inspired by watching Harpo Marx play the harp on an episode of I Love Lucy.

Muhammad was 9 years old, and that was the first time she had ever seen a harp. She was mesmerized. “That’s what I want to do,” she remembers saying. But when she ran out to tell her mom her revelation, she was stopped in her tracks. Her mother had just gotten divorced from her father, and they were struggling, living in what she calls the “projects,” surviving on welfare and food stamps. Playing the harp was not a dream that Muhammad could afford to have. So she put it in the back of her mind, where it lived quietly for the next decade.

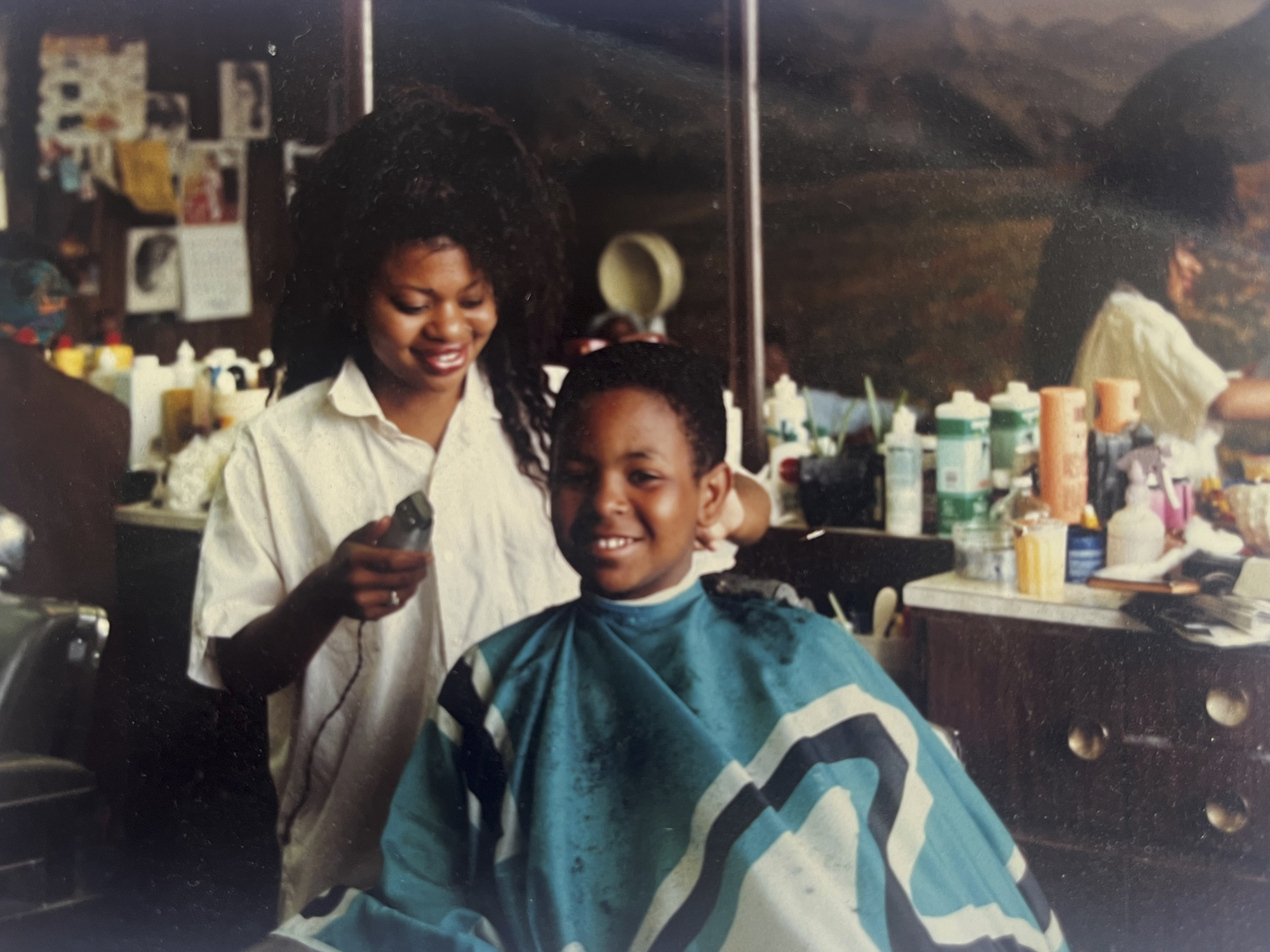

When she graduated high school, she hoped to go to college to finally be able to study music, but financial circumstances required her to follow her mother’s advice instead and get her barber’s license. She opened her first barber shop when she was 21 years old. It was the height of the crack epidemic, but she was making a good living for herself, and she liked the work.

Then, serendipity struck. She was dating a man who was friends with a harp builder.

“That’s when the dream came rushing back,” Muhammad says.

“Didn’t I say I wanted to do this when I was a shorty back in Compton, watching an episode of I Love Lucy? I said I wanted to do this!”

‘Do we, as Black people, do this?’

Muhammad bought her first harp on layaway for $400. But she had no idea how to play it, so she started taking lessons. It was a humbling experience. At 30 years old, she was the oldest student in the class. Her peers also had more resources and a lineage of European classical music training. And one other big thing stood out: the color of her skin. Her friends and family questioned what she, a Black woman, was doing playing a harp: “Do we, as Black people, do that?” she says, remembering those conversations. She recalls one particularly painful moment when a friend called her up to go out dancing.

“‘Hey girl, I can’t go, I’m practicing. I’m learning how to play the harp,’” she told her friend.

The friend says: “‘Harp? Girl, you are old and Black, and we don’t do that.’”

She remembers looking at the phone and then looking at her harp. Back then, she says, you could slam the phone down. But she didn’t. She just hung up and let her talk to the dial tone.

But Destiny Muhammad wasn’t deterred by her friend’s doubts or the obstacles that stood in her way. In her heart, she knew she didn’t have a choice: “Even though the path didn’t appear charted, I knew that I had to move forward on it in the only way I could,” she says. “For Destiny Muhammad, the path was always invisible until I would take the step.”

Her big break came when she started playing at farmers markets around the Bay Area. She would spend hours playing to no one in particular, slowly adding more songs into her sets and then her own improvised pieces as she got more comfortable. And then someone walked up to her and asked her to play at their wedding. That was her first paid gig.

From Celtic to Coltrane

Destiny Muhammad calls her musical style “Celtic to Coltrane.”

“I’m cross-pollinating between straight-ahead Celtic music and straight-ahead jazz… I hear the jazz in the Celtic music,” she explains.

Some of the first songs she learned to play were traditional Celtic compositions. She was captivated by the stories behind these classics, like the Irish song “The Butterfly Jig” from the early 1900s.

Muhammad says that when researching the song, she found it was originally called “The Widow’s Jig” because so many women lost their husbands during the Irish Potato Famine. When these widows came with their children to the United States, the song’s name changed.

“Butterflies are symbolic, at least for me, of transformation and evolution,” Muhammad says. “And that just brought it to life for me. I have kept it in at least a part of my sets because I love that story of transformation.”

The Coltrane in “Celtic to Coltrane” refers to none other than the multi-instrumentalist Alice Coltrane. Known as Alice McLeod before she married fellow jazz musician John Coltrane, Alice was one of the few harpists in the jazz world in the late 1960s. Her music is ethereal, free, and genre-bending.

“I heard Alice Coltrane on the radio on the jazz station. And I’m hearing this pentatonic empress just flourishing. I was like, ‘Oh my God, what is that?’” Muhammad remembers. She plays songs written by both Coltranes in her sets, and you can hear the influence of these two jazz greats in her original compositions.

Composing with the edginess of Oakland

Today, Destiny Muhammad works as a composer, performer and teacher in the Bay Area, where she’s been for the last 30 years. She composes original scores for her group, The Destiny Muhammad Trio.

Her style of composition is personal and inspired by another jazz great: “Duke Ellington would write scores out for his musicians. But as opposed to putting sax here, drum here, he would put the person’s name because he knew exactly how they were going to interpret what he shared with them,” Muhammad says. “And that’s the way I feel with many of the musicians. When I pick a person … I’ve already felt them breathe life into my composition.”

She also doesn’t feel constrained to rely on traditional sheet music notation: “If you ever look at sheet music, especially music that’s scored out for a particular type of ensemble, the composer will have markings or words in there about how to interpret. They might even usually have it in Italian. My Italian is at zero. So I wrote, “‘Give me a gangsta feel right here. Hella gangster right here.’ You know, I live in Oakland. We say stuff like that.”

She says her musicians in Oakland respond well to this unorthodox composition because they play with a unique “gutsiness” and “edginess” that she loves. “There’s a level of refinement without being edited,” she says. “I love Oakland and the Bay Area for that.”