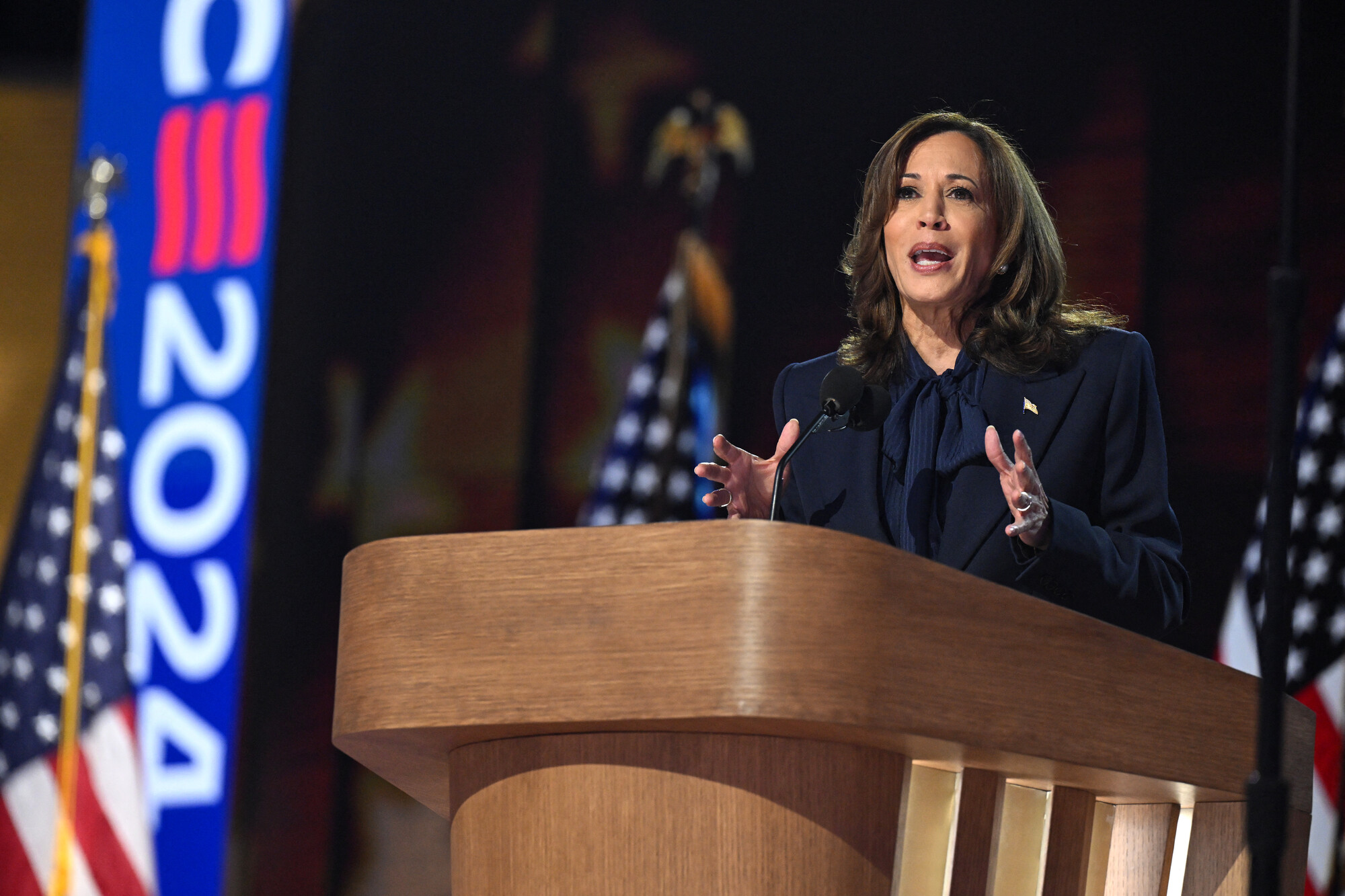

This evening, Harris will participate in the only scheduled presidential debate. Conservative media personalities have assailed her position on reparations as extremist and zeroed in on Harris’ relationship with her pastor, Rev. Amos C. Brown of San Francisco’s Third Baptist Church.

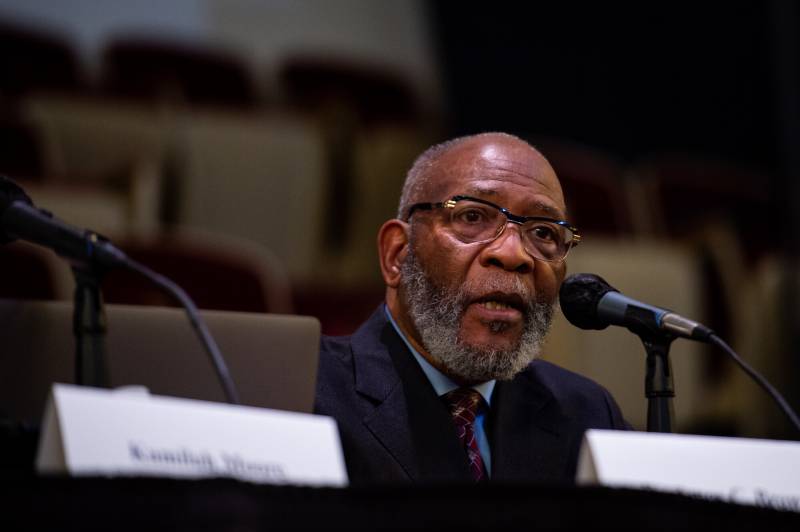

Brown, who led the closing prayer at the Democratic National Convention on the night Harris accepted the nomination, was a member of the California Reparations Task Force. Days after the brutal attack on a Black woman in the Financial District on Sept. 1, Brown, who does not shy away from bringing politics into the pulpit, invited law enforcement and city officials to Third Baptist to address the spate of anti-Black hate crimes in the city.

In the gravelly, Southern drawl that reveals his Mississippi roots, Brown told the small crowd in the pews that the failure of legislators to support reparations was another form of violence.

“We must do something. The time is now for us to stop talking, to stop analyzing. We don’t need to make it a paralysis of an analysis,” Brown, who was also on San Francisco’s reparations commission, told KQED on Thursday. “We have the facts. We got a report on the diagnosis. Now let’s give some sensible, safe prognosis.”

Conservative outlet the Washington Free Beacon has published multiple stories about Harris’ association with Brown, suggesting they share anti-American views. The stories replicate the controversy incited over former President Barack Obama’s connection with Rev. Jeremiah Wright, Obama’s former pastor who was critical of the United States immediately after 9/11.

“We have supported state terrorism against the Palestinians and Black South Africans, and now we are indignant because the stuff we have done overseas is now brought right back into our own front yards. America’s chickens are coming home to roost,” Wright said to his congregation in 2001.

At a memorial service for 9/11 victims, Brown, who knows Wright from their time studying at United Theological Seminary, said, “America, is there anything you did to set up this climate? What did you do, either intentionally or unintentionally?”

In 2008, Brown, the president of San Francisco’s NAACP chapter, wrote an impassioned defense of Wright in the San Francisco Chronicle.

“We are not angry; we are not inflammatory; we just tell the truth with passion and enthusiasm. And we will not be silent when persons mischaracterize our witness as anger,” he wrote.

Marne Campbell, a professor at Loyola Marymount University who provided research for California’s Reparations Task Force, said she makes a point of discussing Obama’s 2008 campaign and the Wright controversy with her African American Studies students.

“People don’t really understand that Black theology is a theology of liberation,” she said. “Language is used in a different kind of way. But in the end, people hear this message and think it’s anti-American. They think, ‘You want to take something away from white people and give it to Black people.”

Nolan Higdon, a professor of history and media studies at UC Santa Cruz, said the strategy of cherry-picking quotes to spread hate is antithetical to democracy. He added that Republicans over the last 50 years have used race-baiting to scare white people into voting for their candidates.

“To amplify fear, division and hate, that’s something that all too often politicians do, and it may be good in the short term for their party or election, but it’s really bad in the long term for the country,” Higdon said.

Higdon said the attack on Brown is also an attack on the Black church, which has long been a safe space to discuss politics.

“And even after slavery, living in the Jim Crow era, the Black church is one of the few, if not only, space in a lot of these communities where Blacks could congregate and talk about these issues,” he said.

The scrutiny over Harris’ reparations stance has also fed into online conspiracies and bizarre memes questioning the legitimacy of her candidacy. One of the most prominent critics of reparations in Congress disparaged Harris for pushing a divisive racial agenda.

“Americans are done with reparations,” Rep. Burgess Owens (R-Utah), who is Black and grew up in the segregated South, said on Fox News in July. “If you look at Vice President Harris, if she were a white person, she would not be sitting in the place she’s sitting now.”

In front of a room filled with Black journalists attending the National Association of Black Journalists conference in Chicago on July 31, former President Donald Trump disputed Harris’ heritage and ethnicity in remarks many attendees viewed as racist.

“I remember back in 2019, 2020 on Twitter, seeing some of the same actors in that space using that same kind of rhetoric — Kamala Harris isn’t Black. Kamala Harris just became Black. Or Kamala Harris isn’t African American,” King Williams, an Atlanta-based journalist, said.

Campbell, who identifies as mixed race, has noticed similar talking points in the reparations argument around Harris.

“Because her father is Jamaican, people on both sides say, ‘You don’t have the same experience as Black people born in America,’ but she does. And she is a Black person born in America,” Campbell said.

When asked about Trump’s false claims about her identity in her first televised interview as the Democratic nominee, Harris declined to entertain the tirades about her race and gender. “Same old, tired playbook,” she said to CNN’s Dana Bash. “Next question, please.”

Over the weekend, her campaign posted a list of policy positions, including protecting civil rights and freedoms, but there was no mention of reparations. The DNC platform, which includes support for Congress to study reparations, was built for President Joe Biden’s reelection campaign. Biden has spoken candidly about race, but he backed off of reparations legislation.