Olivia Allen-Price: I’ve been renting my place here in the Bay Area for 9 years and once a year, around the time when our lease terms are due for renewal. I start to get anxious about what that rent increase might look like.

(Music)

Ericka Cruz Guevarra: That’s a real fear!

Olivia Allen-Price: Renters in California pay about 50 percent more for housing than renters in other states. Which means a lot of people are spending about as much as they can afford on rent.

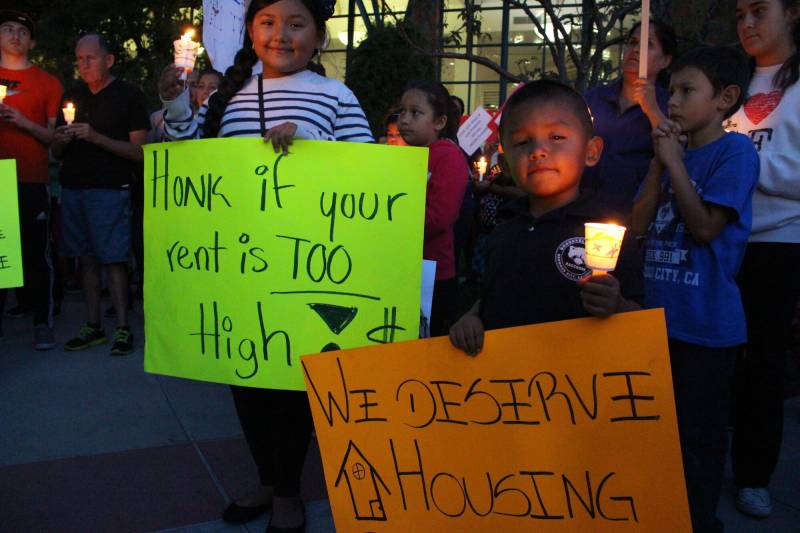

Ericka Cruz Guevarra: Big rent increases price a lot of people out of their homes every year.

Olivia Allen-Price: One way local governments have tried to give renters a bit more stability is by enacting rent control laws.

Ericka Cruz Guevarra: But caps set by the state mean they can only go so far… I’m Ericka Cruz Guevarra, host of The Bay

Olivia Allen-Price: And I’m Olivia Allen-Price, host of Bay Curious. Today we’re moving in on Prop 33, which would give authority back to local governments to enact or change rent control laws.

Ericka Cruz Guevarra: We’ve seen similar props in 2018 and 2020, and voters didn’t go for it. But polling shows the tide could be turning.

Olivia Allen-Price: We’ll get into what exactly Prop 33 would do … plus an overview on the debate about rent control. Does it lower rents? Or have the opposite effect?

Ericka Cruz Guevarra: That’s all just ahead on Prop Fest. Stay tuned…

SPONSOR BREAK

Olivia Allen-Price: Let’s dive deep into Proposition 33, which will read like this on your ballot.

Amanda Font: Proposition 33 is a state statue that expands local governments’ authority to enact rent control on residential property.

Olivia Allen-Price: This is one of the big ticket items on this year’s ballot. With tens of millions of dollars being spent on both sides. Because this one impacts people’s wallets. Here to wade through it with us is KQED housing reporter Vanessa Rancaño. Welcome, Vanessa.

Vanessa Rancaño: Hello.

Olivia Allen-Price: So let’s start big picture. What is Proposition 33 aiming to do?

Vanessa Rancaño: It aims to give local governments more power to regulate rents. They do this via rent control laws. So these are policies that cap annual rent increases. At the moment, there’s a state law that sets some parameters on how far rent control Laws can go in California. But if Prop 33 passes, those limits would be removed.

Olivia Allen-Price: There is rent control already in some Bay Area cities like San Francisco, Oakland, San Jose. So cities do have some ability to enact rent control, right?

Vanessa Rancaño: Yeah, they definitely do, but they can only go so far. And that’s because of this state law called the Costa-Hawkins Rental Housing Act that’s been around since 1995. And it’s sort of key to understand that before we can unpack Prop 33.

(Music)

Olivia Allen-Price: All right. Well, let’s get into Costa-Hawkins, Where to begin? Walk us through it.

Vanessa Rancaño: Sure. So the context for this law is that there was a swell of tenant activism in the 70s and 80s, which led to the passage of a number of local rent control laws. And at the time, people were struggling to pay rent for a bunch of reasons. We weren’t building enough, there was inflation, wages weren’t rising. And in 1978, Prop 13 passed here in California, limiting property taxes homeowners pay.

Now, tenants had been promised that because landlords would be paying less in taxes, those savings were going to trickle down to them and they’d be paying less in rent. But that did not happen. Rents, in fact, rose. And tenants rights groups felt duped.

So in response to all these different factors, we saw a handful of cities pass rent control laws that limited how much a landlord could raise rent.

What we see then is a backlash against that increase in tenant power. Some people blamed rent control for the housing shortage. They thought rent control scared off developers from building new apartments because they wouldn’t be able to make as high a profit.

So that’s the background when in 1995 these two state lawmakers, Democratic Senator Jim Costa and Republican Assemblymember Phil Hawkins, put forward legislation to curb rent control. It passes by just one vote and shapes rent control policy across California for decades.

Olivia Allen-Price: Now, what exactly does Costa-Hawkins do?

Vanessa Rancaño: So it does two big things. It exempts single family homes, condos and anything built after 1995 from rent control. That’s why you see rent controlled units tend to be older. The idea there is that to encourage new construction you’ve got to exempt new apartments from rent control. For cities that had existing rent control laws in place Costa-Hawkins froze the cutoff dates for how old a unit had to be to be eligible for rent control under those laws. So, for example, in Oakland, the cutoff is 1983. Berkeley, it’s 1980. San Jose, San Francisco—nothing built after 1979 can have rent control.

The second really important thing that Costa-Hawkins does is it eliminates what’s called vacancy control. That ties rent control to an apartment instead of to the tenant. So under Costa-Hawkins we have vacancy decontrol. It means that if a tenant moves out of a rent controlled apartment, the landlord can raise the rent up to market rate, as high as they want. They’re only limited in terms of how much they can raise the rent a year to year after a tenant moves in.

Olivia Allen-Price: At this point Costa-Hawkins has been on the books in California for just shy of 30 years. Can you talk about what kind of impacts have seen?

Vanessa Rancaño: Well, I think we can say that we see fewer people Living in rent controlled apartments than we might otherwise. We also see rent control apartments getting older. So our stock of rent controlled apartments dwindles because buildings get redeveloped. I think it’s really hard to say if limits on rent control have had any impact on development because there are just so many other factors in play.

Olivia Allen-Price: But developers would certainly say that they like them, I would assume.

Vanessa Rancaño: Yes.

Olivia Allen-Price: So this year we’re voting on Prop 33. What would it do exactly?

Vanessa Rancaño: It would take us back to before Costa-Hawkins and hand the power to make decisions on rent control back to local governments. To be clear, it does not mean that suddenly rent control is going to be in every town, affecting every home or anything even close to that. But it does open the door for communities to make local rent control decisions without being limited by state law.

Olivia Allen-Price: I feel like I’m having déja vu with this one because people have tried to overturn Costa-Hawkins before. Right?

Vanessa Rancaño: Yeah, there were two efforts, one in 2018 and one in 2020, that took aim at the law and voters shot both of those down. There are some powerful interests that really do not want to see the expansion of rent control. Landlord groups, real estate groups. They have put a lot of money into fighting these statewide initiatives and they have so far been successful.

Olivia Allen-Price: Now, rent control is controversial even among those who want to see lower rents. Can you explain why?

Vanessa Rancaño: Yeah. I mean, traditionally, economists have seen rent control as a really bad idea. They argue that rent caps are inefficient, that they create scarcity and drive up rents in non-regulated buildings. I came across this survey from 1992 that found over 90% of economists agreed that these policies drive down the quantity and quality of available housing.

Olivia Allen-Price: Ya know, Bay Curious actually did an explainer that covered some of those things about rent control back in 2018. So I would say if the efficacy of rent control is really important to how you vote, you might go give that a listen for some additional context. We’ll link to it in our show notes or just head online and search something like: “Bay Curious Rent Control 2018” and it should be the first thing that pops up.

Vanessa Rancaño: Yes, that is a great overview of the arguments. I think the only thing I would add is that more recently we have seen some economists come forward to argue that there is research and there are real world examples that refute this traditional narrative, which they say is based more on economic theory than empirical evidence.

Mark Paul is a Rutgers economist who studies rent control and also very much supports it.

Mark Paul: Most mainstream economists are taught these theoretical models where perfect competition exists, there’s no such thing as market power, you know where landlords have more power than renters. In their models that they’re thinking about this there’s unlimited supply of affordable housing, homelessness doesn’t exist, and corporate landlords that use algorithmic pricing to jack prices up, something that we see the Federal Trade Commission going after corporate landlords for, things like that can’t exist because they would just get outcompeted. But I think people underestimate the bias most economists have against government intervention.

Olivia Allen-Price: Hmm so it sounds like not all economists are necessarily on the same page the way they might have been at one time?

Vanessa Rancaño: Yes. So last year, a group of 32 economists wrote this letter to the Federal Housing Finance Agency lobbying for the use of rent control across the country. And what they’re arguing is that all this naysaying that we see about rent control mirrors economists’ traditional opposition to minimum wage laws. They predicted that minimum wage laws were going to lead to widespread joblessness, and we haven’t actually seen that happen.

Olivia Allen-Price: Hm Interesting. Are there any components of rent control that folks who do study this can agree on?

(music)

Vanessa Rancaño: So here is what I think we can safely say. There is research evidence that rent control does work to hold rents down for tenants in eligible units. But how much varies a lot across policies and studies. There is also evidence that it can have unintended consequences.

So the places where there’s agreement about what those consequences are: that it can lead to a decline in housing quality, because landlords have less incentive to maintain their properties. It can lead to a reduction in the number of rental housing units on the market because landlords convert apartments to condos. So there are studies that have found that more moderate forms of rent control can avoid some of these unintended consequences. And then the economists, those who support rent control argue that if you put in place other regulations, along with rent control, you can get around some of these consequences.

So, for instance, you can do things to try to prevent landlords from converting their apartments to condos. You can allow landlords to pass along maintenance costs to renters to sort of incentivize them to continue to maintain their properties. So things like that.

Olivia Allen-Price: I know one critique of rent control has been it can be pretty blunt in terms of who it actually helps. Can you explain that?

Vanessa Rancaño: I will say that you know, there are many people who argue that even if you put in place the strongest, best rent control policy, it’s not necessarily going to reach the right people, right? Because it is tied to a property rather than a person. Michael Manville is a UCLA Urban planning professor who studies rent control.

Michael Manville: If we’re serious about helping our most vulnerable tenants, that’s really going to involve some combination of making housing in general just much more plentiful, and spending money in targeted subsidies for low-income people. Because the thing is, even if you have the most powerful, strong rent control law, you could end up holding down the rent for a bunch of people who don’t necessarily need that assistance. And letting a bunch of people who do need that assistance pay a very high housing costs because they aren’t fortunate enough to be in a rent controlled unit.

Olivia Allen-Price: All right. Walk us through who is opposing Prop 33 and why.

Vanessa Rancaño: In general, it’s landlord and real estate interests. And what they argue is that these policies ultimately are counterproductive, that they will lead to less new construction and ultimately housing prices will just go up, that rental prices will go up. I’ve also heard from landlords that, you know, their property taxes keep going up, but they’re seeing stricter caps on how much they can raise the rent and that makes it really tough for them to maintain their properties. And many of them are just really frustrated.

Olivia Allen-Price: Who is supporting this measure and why?

Vanessa Rancaño: So the AIDS Healthcare Foundation and its president, Michael Weinstein is the chief proponent of not just Prop 33, but also the last two attempts to roll back Costa-Hawkins in 2018 and 2020. The California Democratic Party is also backing it. Some tenant advocacy groups. Some unions. Francisco Dueñas runs Housing Now California it’s a coalition of organizations advocating for pro renter policies. They very much support Prop 33.

Francisco Dueñas: We see that they help provide stability for tenants. That it helps prevent or protect against, you know, surprise increases in rents. And I think that’s the biggest benefit that people really look towards, is just knowing that their rents are not going to rise 100%, you know, from one month to the next when they’re lease ends.

Vanessa Rancaño: And in general all these folks argue that the rent is just too high, that people are getting pushed out of cities. People are ending up homeless. And, you know, at the very least that we should do something to protect people from huge surprise rent increases. They point out that while we do have a state rent control law, it passed in 2019 and it limits annual increases to 10%, it’s just too high, they say. And that law sunsets in 2030 in any case.

Other arguments I’ve heard are that homeowners are benefiting from a form of price control in the form of fixed rate mortgages. And we should, you know, extend similar protections to renters.

Beyond all that, there are people who argue that we should rethink how we approach housing in this country, that we should reframe it as a fundamental human right rather than a commodity. And they see rent control as one small step in that direction.

Francisco Dueñas: The profit motive shouldn’t be the only thing that leads the policy when it comes to housing because then, you know, everybody but the highest bidder is losing out if our housing policy is only focused on profit and, you know, outcomes.

Olivia Allen-Price: I do want to underline that support coming from the AIDS Healthcare Foundation on this prop, because that plays into what we’ll be talking about tomorrow, Proposition 34, which some have seen as a proposition built specifically to take aim at the AIDS Healthcare Foundation for their advocacy on rent control issues over the years.

Olivia Allen-Price: Vanessa, this is one of the most expensive measures from a spending perspective that we’re seeing. Can you tell us how that’s all shaking out so far?

Vanessa Rancaño: Oh my god. People are spending so much money on this. So to date, it’s over $40 million to support this proposition. The vast majority of that is coming from the AIDS HealthCare Foundation. In terms of opposition, they’ve raised over $65 million. The vast majority of that is coming from the California Apartment Association and the California Association of Realtors.

Olivia Allen-Price: Woo! Spendy. Vanessa Rancaño is a housing reporter at KQED. Vanessa, thanks for breaking this down for us.

Vanessa Rancaño: Thanks for having me.

Olivia Allen-Price: Let’s review. A vote yes on Prop 33 means you want local governments to have the power to enact or change their own rent control laws. A vote no on Prop 33 would keep state limits on rent control in place.

Olivia Allen-Price: That’s it on Prop 33. You can find audio and transcripts of this episode, and all the others in our Prop Fest series at KQED.org/propfest. While you’re on the KQED website, be sure to check out our voter guide, which has lots more important information about your statewide and local elections.

Ericka Cruz Guevarra: Prop Fest is a collaboration between The Bay and Bay Curious podcasts. It’s made by…

Alan Montecillo

Olivia Allen-Price

Jessica Kariisa

Amanda Font

Christopher Beale

Ana De Almeda Amaral

And me, Ericka Cruz Guevarra

Olivia Allen-Price: We get extra support from

Jen Chien

Katie Sprenger

Maha Sanad

Holly Kernan

And the whole KQED family

Ericka Cruz Guevarra: Tomorrow we will get into Prop 34, which would limit how some healthcare providers can spend money earned through a federal drug pricing program.

Olivia Allen-Price: It looks like a healthcare bill, but it actually has a lot to do with rent control. We’ll spill the tea on that tomorrow – but be sure you’re subscribed so you don’t miss out.