Episode Transcript

Olivia Allen-Price: I’ve been hiking around the Bay Area for more than a decade, and really make a point to try and get to new places – but I know I haven’t even discovered half the hikes this region has to offer. I often find myself turning to online guides and maps to find new trails in this outdoor haven.

But for San Francisco resident Ryan Flynn, the quest to find a perfect new hike took a more… explosive turn.

Ryan Flynn: I was just kind of looking for hikes for my wife and I to do on a weekend. So I was just on Google Maps, and I happened to see a little pin for, like, a historical marker for the first dynamite factory in the United States. And that was very surprising. So I figured I would reach out to you guys.

Olivia Allen-Price: The pin Ryan stumbled across marks the location of California Registered Historical Landmark No. 1002. If you enter Glen Canyon Park from Elk street, you’ll see it.

Evelyn Rose: So it’s titled “The first dynamite factory in America. Giant powder company, under personal license of inventor Alfred Nobel, began producing dynamite here on March, 1868. On November 26, 1869 a massive explosion leveled the complexes, buildings and fences. [talking fades under…]

Olivia Allen-Price: For Ryan, this all came as a shock. So he sent in this question …

Ryan Flynn: What is the history behind Glen Canyon Park being the first dynamite factory in the US?

Olivia Allen-Price: I’ve run through Glen Canyon Park a few times and – safe to say – dynamite was not top of mind. But turns out, this peaceful park has a turbulent backstory dating back to the mid 19th century, when Alfred Nobel – yeah like the Nobel Peace Prize – invented dynamite.

Today we’ll learn how dynamite made its way to San Francisco … and why it was such a transformative product in this state. Plus, we’ll explore the stories of Chinese laborers who often had the most dangerous jobs of all in the high explosives industry.

One quick heads up: There are a few gory details about the aftermath of explosions in this episode.

You’re listening to Bay Curious. I’m Olivia Allen-Price. Stay with us.

[SPONSOR MESSAGE]

Olivia Allen-Price: To help us answer Ryan’s question about the history of the first dynamite factory in the US, right here in SF’s Glen Canyon Park, we’ve put Bay Curious reporter Gabriela Glueck on the job. To kick off her reporting, she headed over to the park to meet up with one of the people responsible for placing that historical plaque.

[sounds of wind and birds chirping in a park]

Evelyn Rose: I see this piece kind of catch my eye in the dirt by the trail. And I lean down and pick it up, and it’s, it’s blue with kind of the shape of a candy corn.

Gabriela Glueck: That’s Evelyn Rose, she’s a long time Glen Park resident, pharmacist by training, and passionate neighborhood historian.

Evelyn Rose: And I’m looking at it and realize, ‘Oh my gosh, this is probably a piece of melted glass from the explosion.’

Gabriela Glueck: For Evelyn, her dynamite journey started in the pages of an old book.

Evelyn Rose: And in it is a very grainy image of what they claim is the first — the site of the first dynamite factory in the United States. And as I read the caption, it says the Glen Park playground in San Francisco, and I about fell out of my chair because it’s like, ‘Oh, my God, that’s like a block from my house.’ Had no idea….. and so it started an 11 year journey to discover the history of the dynamite factory and to get the plaque.

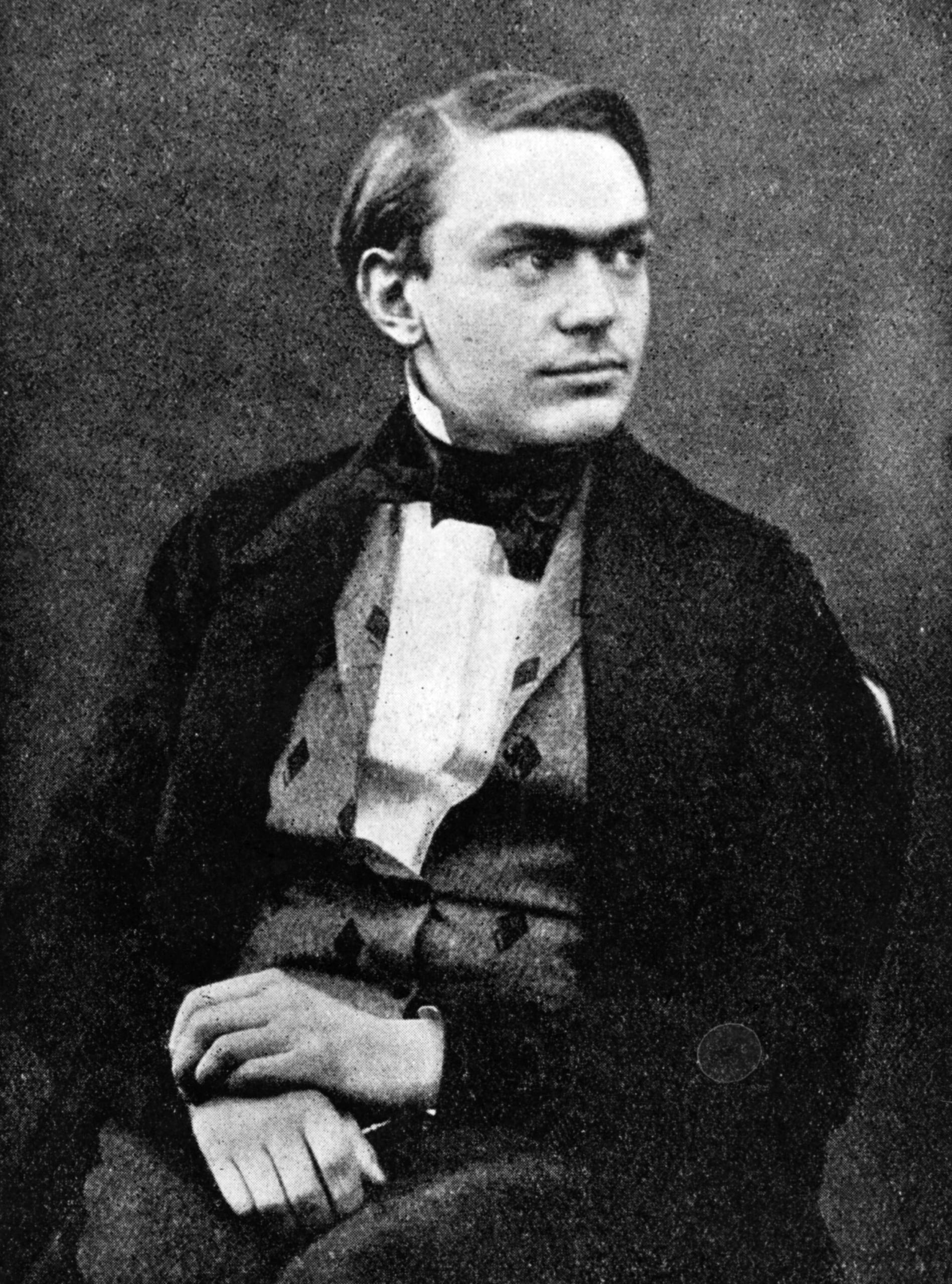

Gabriela Glueck: The story of how dynamite made its way to Glen Canyon Park starts in 1860s Sweden… with a young inventor named Alfred Nobel. He was experimenting with nitroglycerin, a highly explosive yet highly unstable chemical compound that just too often went boom.

He became the first to start manufacturing the substance on an industrial scale. And when he came up with a safer way to detonate it, California businessmen began to take notice. With their hands tied up in mining and railroad building, — Nobel’s innovations were… intriguing.

Evelyn Rose: And through a friend in Paris, whose brother was here in San Francisco… he licensed nitroglycerin oil to the brother of his friend, and the company was called Bandmann & Nielsen, and so they were the exclusive agent selling oil of nitroglycerin along the Pacific coast and this is about 1866.

Gabriela Glueck: Soon thereafter, the first crates of nitroglycerin oil arrived in San Francisco. And for California industries, the arrival of Nobel’s blasting oil was transformative.

Before nitroglycerin, black powder was America’s main explosive. First brought to California in the late 1840s, when miners started using it in their search for gold, the chalky powder soon became the primary blow-things-up agent in the early California mining and railroad industry. But for more than a handful of construction projects, black powder and a hand chisel just wasn’t going to cut it. And when some of those first crates of nitroglycerin oil arrived at the Central Pacific Railroad, it seemed that Californians might have struck a new kind of gold.

[sounds of boxes being moved and bottle clinking]

Yet one of the crates from that first shipment had been left behind in San Francisco… in the back room of the Wells Fargo building, among the other unclaimed freight.

And it was leaking….

Voice Reading Newspaper Clipping: “On Monday, 16th, in San Francisco at fifteen minutes past one o’clock, P.M., an explosion took place in the storeroom back of Wells, Fargo & Co.’s building which demolished everything within a circuit of 40 or 50 feet. The explosion was so powerful as to shake the earth like an earthquake for a circuit of a quarter of a mile…

Fragments of human remains were found scattered in many places. A piece of human vertebrae was blown over the buildings on the east side of Montgomery street. A piece of skull was lying on California street, east of Leidsdorff, with other fragments of human remains, and a human arm struck the third story window of the building across the street.”

Gabriela Glueck: That’s an excerpt from the pages of The Placer Herald on April 21st, 1866. The nitroglycerin disaster left San Franciscans in a panic, killing at least 15 people and maiming even more. And countless other such explosions of Nobel’s volatile blasting oil in the United States and across the globe did nothing to settle fears.

In response, California seized all private holdings of nitroglycerin and banned its transportation within state bounds.

Evelyn Rose: Scores of people were dying around the world, and Nobel became known as the demon of death, and he was a pacifist, you know, and he was devastated that he was being associated with nitroglycerin in that way. So he set out to find a safer form.

Gabriela Glueck: For Nobel, the quest to tame nitroglycerin was personal too. His younger brother had died in an explosion at Nobel’s nitroglycerin factory. But the question of how best to stabilize such a volatile and deadly substance was, as of yet, unanswered.

Evelyn Rose: Quite by accident, when nitroglycerin oil spilled and somehow there was this clay nearby. The clay absorbed it and created kind of a putty, and he realized that completely stabilized nitroglycerin.

Gabriela Glueck: Nobel patented that accidental discovery and named the stabilized nitroglycerin… dynamite. And that’s the story. Dynamite is born and Nobel starts cashing in, his profits from dynamite along with his guilty conscience about its deadly potential eventually motivated him to start the Nobel Prize in the hopes of shifting his legacy from one of destruction to peace.

Now, as for when Dynamite made its way to Glen Canyon Park … that comes in 1868, when Nobel gave Julius Bandmann – that brother of a friend from earlier – license to start manufacturing dynamite in the States. Bandmann rallied a group of San Francisco investors around this new innovation and soon founded the Giant Powder Company.

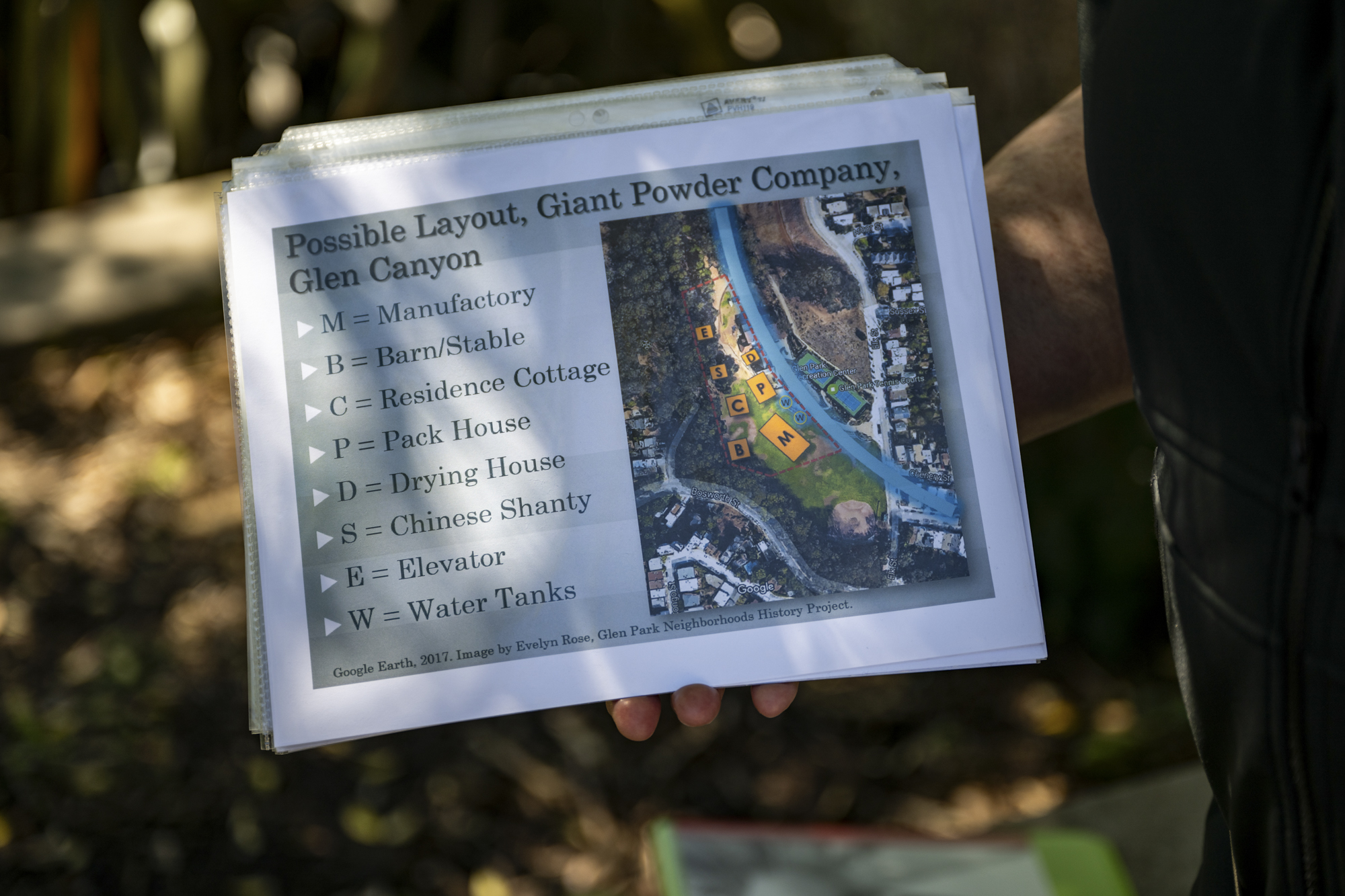

Evelyn Rose: The President was a gentleman named L L Robinson and he had invested, along with some other gentleman in the land that included Glen Canyon. He leased to the company four acres of land that today surrounds where today the Glen Park Recreation Center is.

Gabriela Glueck: At the time, Glen Canyon Park was pretty barren. A canyon full of cows. But soon enough, Giant Powder started manufacturing dynamite. The factory was run by a handful of chemists and eight Chinese workers who did most of the heavy lifting. And with production in full swing… competitors started cropping up.

But America’s first dynamite factory didn’t last very long.

[dramatic music, sounds of wind blowing]

Gabriela Glueck: It’s November, 1889 and the Chief Chemist of Giant Powder Company, Dr. John Bussenius, is sitting in his cottage with his assistant, Alfred Wartenweiler.

Evelyn Rose: They just had dinner, the door was open, so it must have been a little bit of a balmy night.

Gabriela Glueck: That’s Evelyn Rose again, Glen Park resident and neighborhood historian.

Evelyn Rose: The Chinese workers were in their cottage having dinner, and they were about to play cards in the cottage. And Charles Cook, the teamster, comes to the door and says, you know, everything’s secure. The horses are stabled. And Wartenweiler, the assistant just happens to look out the door that faces the manufactory, and he sees a fire, and he yells, “Fire!” and he dived for the door… All of a sudden there was this massive explosion.

[Explosion sound]

Evelyn Rose: And a home 300 yards away was nearly taken off its foundation.

[sounds of crackling fire and crumbling structures]

Evelyn Rose: The site is obliterated. The teamsters wagon has been thrown 150 yards away. Chinese workers were severely burned. Waltenweiler was found 50 yards away under a bunch of lumber. Diving for the door had saved his life. He was injured. But you know, survivable, and it wasn’t until later that they found the burned bodies of Cook and Bussenius. Bussenius was identified—he wore a gold watch, he always had it on, and that was the only way they could identify him.

Gabriela Glueck: The exact cause of the explosion remains unknown, but in general there weren’t great safety practices at the time. As for the Chinese workers and how they fared in the aftermath of the explosion, details are sparse. There is however brief mention of the laborer’s outcomes in the pages of the Sacramento Daily Union days after the disaster.

Voice Reading a Newspaper Article: “On the ground in the vicinity of the Chinese house were six or seven wounded Chinese men. They were taken in a wagon and conveyed to the city, and are now in a house on Commercial street, above Kearny. Their names are Ah Chum, Ah Chow, Ah Sing, Ah Moy, Ah Gne, and Ah Choy.”

Evelyn Rose: I still hope someday to find out more about them, because if we have their names, there should be something. There should be reports in perhaps Chinese newspapers from the time that somebody might be able to research and translate, because I would love to know what their outcomes were.

Gabriela Glueck: The story of the Chinese laborers who worked at Glen Canyon Park, producing the first dynamite in the United States, risking limb and life in that effort is one we are still working to piece together.

We don’t have personal testimony and there’s little individuality described in the historical record. But in the grand scheme of California industrial history, this oversight is not an anomaly.

Before Chinese laborers stepped foot in Glen Canyon Park, Chinese Americans already had a storied history with early explosives like nitroglycerin blasting oil and black powder, as they worked to build the Central Pacific Railroad.

[Music gently fades in]

Gabriela Glueck: And while little is known about Giant Powder Company’s first Chinese workers, recent research has uncovered much about the experience of Chinese railroad workers’ use of early explosives. Understanding that story and context, can help us get a better grip on the contribution of Chinese laborers to dynamite manufacturing in the United States. Which is why I headed over to Stanford’s campus to talk with Roland Hsu.

Roland Hsu: I’m Director of Research of the project at Stanford University on the Chinese railroad workers in North America.

Gabriela Glueck: Roland has spent years digging through the archive, searching for clues in an effort to better understand the experience of Chinese laborers on the railroad.

Roland Hsu: So the Chinese were both, were both useful and expendable from the point of view of the construction company.

Gabriela Glueck: Chinese immigrants originally started coming to California in the mid 19th century. They came with the Gold Rush, with hopes to strike it rich in a new and uncharted land. But they encountered hostile racism, and a lack of legal standing for land claims that made that hope an impossible dream… so they looked elsewhere for work… but they weren’t seen as choice number one for manual labor.

Roland Hsu: We do know that the Irish workers who were brought in quickly found this to be inhuman conditions. Dropped their pickaxes and shovels and walked off the job

Gabriela Glueck: With the clock ticking, the Central Pacific Railroad turned to Chinese labor. By the end of construction, they had hired an estimated 20,000 Chinese workers to build a railroad across America.

It’s almost hard to explain just how challenging of a construction project this was. Railroads at that time could only really climb around a 2% grade. But this is the Sierra Nevada range we’re talking about, with its absurdly high granite faces and sheer rock cliffs. And the task was simple: Just tunnel through it all.

[Music, the sounds of pickaxes and loud thuds against stone]

Roland Hsu: So by hand. They’re using iron pickaxes, iron bars to just break granite rock. Four men would take a very large, heavy iron bar, slam it in unison into the face of Granite Mountain to carve out small niches, and then [were] instructed to pack it with nitroglycerin, light it and run.

Gabriela Glueck: If you’ve been paying attention to this story so far, you know that it doesn’t take much for nitroglycerin to go boom… and worker safety wasn’t a big conversation point in 19th century railroad construction.

Roland Hsu: It is a one of the more evocative stories of the experience of the Chinese who built a railroad to be…. lowered in baskets off of long ropes, you know, hundreds of feet down from the top of a sheer cliff by hand, individually cutting a notch and then packing it with they turn use the term black powder, and then pulling frantically on the rope.

Gabriela Glueck: Chinese immigrants built the railroad, using these early explosives, but their story and contribution – much like their contribution to dynamite production in Glen Canyon Park – has largely been erased.

Roland Hsu: We have celebrated the Central Pacific line, the transcontinental railroad, we’ve celebrated it on every 50 years as a tremendous feat. Only recently, on the 150th anniversary, did we finally, finally acknowledge, and not only acknowledge but celebrate that it was predominantly Chinese immigrant labor that built this.

Gabriela Glueck: While these stories didn’t circulate broadly until recently, tales of the railroad and early explosives did make their way through Chinese communities at the time, especially in California. And, pulling this all back to Glen Canyon Park and the eight Chinese laborers who toiled away at that first factory, we can only imagine that they would have been familiar with this history too.

Roland Hsu: We are in the realm of speculation only because, consistently, their identities are obscured so we can’t look for their own personal testimony. We can piece together that the story of the experience of constructing the railroad was passed down with extensive detail to their own families, certainly back in the villages, their home villages, many testimonies that would be perpetuated by song so to the extent that They could transmit their story across the Pacific Ocean, perhaps they could transmit it all the way to Glen Park.

Gabriela Glueck: While the factory in Glen Canyon Park lasted a few short years, the American entrance into high explosive production was just beginning. Nascent competition created new and innovative dynamite-like products and Giant Powder Company continued manufacturing Nobel’s creation… just not in Glen Canyon Park. After the initial explosion, the factory moved to the sand dunes near what is now Golden Gate Park. Then, a few years later, it exploded again, and the city kicked all dynamite manufacturers out. That forced them across the Bay, establishing the East Bay dynamite district, stretching out the economic fabric of the region.

As dynamite manufacturing disappeared from the city, the site of the first factory at Glen Canyon Park began to fade away in the minds and memories of its residents.

[Park sounds fade in… birds, wind, relaxing music begins]

Gabriela Glueck: Today, traces of this explosive history are now long gone. The remnants of the dynamite factory are nowhere to be seen and when you walk into Glen Canyon Park, the first thing you see are baseball fields. There are kids, shin guards on, heading to soccer practice. Friends picnicking on the grass. Parents chatting on the playground benches.

There’s nothing that might suggest a memory of anything besides peace… save for the lonesome plaque… and Evelyn.

Evelyn Rose: If I’m driving by, walking by, sometimes I’ll sit on the bench and just watch people stop and look at the plaque, and they’re and you can just see them. Their heads go back, you know, they’re puzzled, like what here? And so the fact that you’re interviewing me today because of someone’s experience, just like that, I’m just thrilled you know that the plaque can commemorate that you know, and remember a tragedy did happen here. I mean, it is a recreation area today, but also that we do have this link with Nobel Prizes, you know. So going from destruction to peace, I think is an important connection.

Olivia Allen-Price: That was Reporter Gabriela Glueck.

Olivia Allen-Price: Big thanks to our question asker Ryan Flynn, and to Seth Lunine, with the Department of Geography at UC Berkeley, who was a helpful resource for this story.

The holiday season is coming up, and for many of you that means a long car trip to visit friends or family. We’ve created a kid-friendly playlist with some of Bay Curious’s greatest hits for your listening pleasure as you drive. Find it at BayCurious.org, and we’ll drop a link in the show notes too.

Ryan Flynn: Bay Curious is made in San Francisco at member-supported KQED.

Our show is produced by Amanda Font, Christopher Beale, Ana De Almeida Amaral and me, Olivia Allen-Price. Extra support from Jen, Chien, Katie Sprenger, Maha Sanad, Holly Kernan and the whole KQED family.

I’m Olivia Allen-Price. Have a great week.