Episode Transcript

Olivia Allen-Price: During the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic, we all had our little escapes. Places away from the confines of our quarantined homes to get some fresh air … and remind us that despite the distance, the rest of the world still exists. After moving to San Francisco in 2020, Robbie Rock discovered his special spot: a public art installation called the Wave Organ. It’s at the very end of a jetty sitting out in the bay, across the way from The Palace of Fine Arts.

Robbie Rock: It’s just a really cool place to sit, watch the waves, and also to, like, hear the organ.

Olivia Allen-Price: The Wave organ is not like the massive trumpeting organs that you’ll find in a church. Its appearance and sounds are a bit less opulent, but the organ still produces a pretty grand orchestra of gurgles, hisses, and booms.

[distorted gurgling from the Wave Organ]

Olivia Allen-Price: But after all of his visits, Robbie still never really knew what, exactly, he was listening to.

Robbie Rock: I just had so many questions about it. Why is it there, and how does it even work?

Olivia Allen-Price: And of course…

Robbie Rock: When is the best time to hear it?

Olivia Allen-Price: I’m Olivia Allen-Price. This is Bay Curious — the podcast that answers your questions about the San Francisco Bay Area. This week, we’re turning an ear to the waters of the bay.

Now, this episode is probably going to sound best with headphones, but if you’re listening on speakers, you might just want to crank it up. Stay with us.

[SPONSOR MESSAGE]

Olivia Allen-Price: To learn more about this instrument that’s being played by the bay itself, we sent out Bay Curious intern, Ana De Almeida Amaral.

Ana De Almeida Amaral: Out in the Marina district of San Francisco, just off Marina Boulevard, a jetty stretches out into the bay — It’s a man-made stretch of land protecting the docks of St Francis Yacht Club. I went there on a windy morning to visit the Wave Organ. The Wave Organ is an art installation that is partially underwater at the edge of the jetty. It’s an environmental sculpture that interacts with the natural sounds of the waves to create a unique auditory experience.

[Ambient sound of the Wave Organ]

Ana De Almeida Amaral: I called up Ken Finn, an educator at the Exploratorium, which is the interactive science and arts museum in San Francisco. The organ is one of the few exploratorium exhibits that is outside the walls of the museum, and it’s free! I asked Ken to show me around the Wave Organ for the first time.

Ken Finn: A personal favorite time to come out here…[laughs] when a storm is brewing.

Ana De Almeida Amaral: The Wave Organ is a really unique installation. It looks kind of like a Roman ruin — with various slabs of granite creating different viewing levels and stone stairs leading down to the water’s edge. The organ itself is all around the installation. There are 25 organ pipes that peek out like periscopes. And visitors can place their ear next to each pipe in order to hear what is going on underwater. As I climbed around the installation with Ken, we approached an organ pipe.

Ken Finn: Here’s one of the first pipes. And you can see now that the tide is low. You can almost trace it in its winding path down into the bay. I’m going to give it a listen here… Oh, nice.

Ana De Almeida Amaral: Then, it was my turn to listen….

[Distorted swishing sounds from the Wave Organ]

Ana De Almeida Amaral: That’s beautiful!

Ana De Almeida Amaral: With the tide out, the lower water level exposes the length of the pipes. Some only reach out 3 or 4 feet into the bay, while others extend out deep into the water. Then, Ken points at a stone slab on the staircase.

Ken Finn: I like to call out that on some of these, you can see the leftover red paint, so you can tell there’s a red zone. So, some of these were old curb stones from parts of San Francisco.

Ana De Almeida Amaral: That’s because most of the stone slabs used to make the sculpture are recycled pieces of granite. The jetty was originally built using stone slabs from fallen buildings after the 1906 earthquake and headstone remnants from the cemetery relocations of the early 1900s. Many still had beautiful carvings and designs, and they were given a new life with the creation of the Wave Organ.

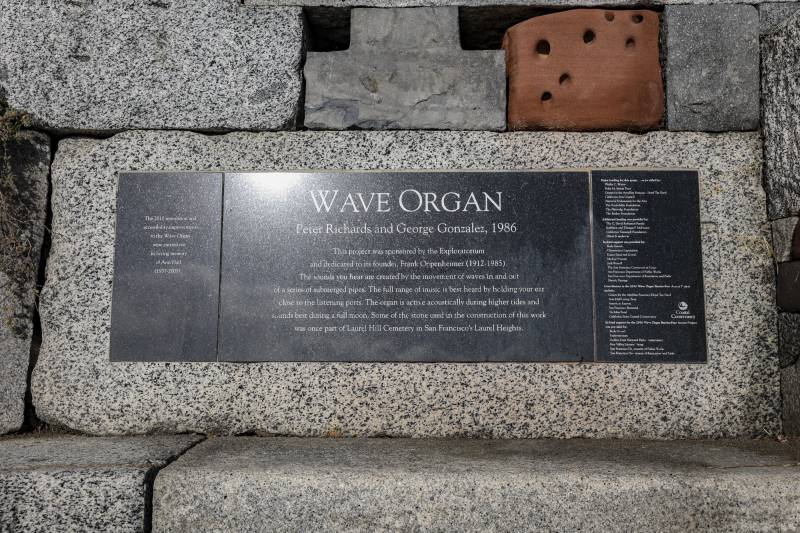

The Wave Organ was created by artist Peter Richards in collaboration with master stonemason, George Gonzalez. Peter Richards is now a senior artist emeritus at the Exploratorium, but back in 1970 he was a recent MFA graduate and new to San Francisco.

Peter Richards: It was the first time I was near a place that had tides. So, I was inherently curious about them and how they worked.

Ana De Almeida Amaral: He was enamored by the changing tides and the way they revealed an intimate connection between us — and the sun and the moon. He was also inspired by a recording he had heard from artist Bill Fontana — who had recorded the sounds of cylindrical pipes he found in a concrete dock in Sydney, Australia. Peter was drawn in by the rhythmic, distorted, and almost mesmerizing qualities of this audio portrait.

Here’s a little excerpt of that.

[Splashing sounds]

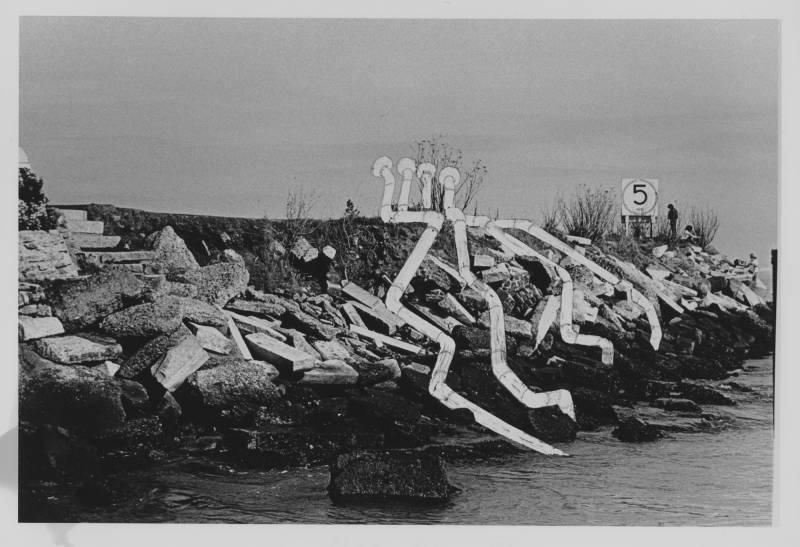

Ana De Almeida Amaral: Peter wanted to see if he could intentionally create this phenomenon. So he took PVC pipes out onto the jetty just across from the Exploratorium, which at the time was housed at the Palace of Fine Arts. And he began testing the sounds of different pipe lengths and configurations. What he found was that the sound from the pipes changed depending on the water level within the pipe…

Peter Richards: So at High tides, the air columns are shorter, so the sounds are higher. And if you go to the low tide, it produces lower frequencies.

Ana De Almeida Amaral: The pipes function like a pan flute. In the Wave Organ, each pipe is a vibrating column of air that amplifies the sounds produced by the moving water. Certain sound frequencies created by the waves are amplified depending on the length of the pipe. And this is what creates a distorted orchestra of underwater sounds.

Once he made this discovery, Peter built a prototype of the Wave Organ for an experimental music festival in 1981. He constructed a rudimentary version at the same spot on the jetty.

Peter Richards: At that point, it was done very crudely. But we did mic it and run a telephone wire back to the Exploratorium.

Ana De Almeida Amaral: The telephone wire ran across Marina Boulevard and all the way to the Palace of Fine Arts.

Peter Richards: So we had the sounds from the Wave Organ sort of echoing through the museum.

[Sounds from the Wave Organ]

Ana De Almeida Amaral: And visitors loved it!

Peter Richards: At that point the Director Frank Oppenheimer said, “Well, we’ve got to do something with this.” So that’s when I started working seriously on it.

Ana De Almeida Amaral: After working to secure funding, the Exploratorium was ready to break ground on a permanent installation. That is when Peter met George Gonzalez and invited him to be the stonemason on the project.

Peter Richards: During the conceptual development of the project, I had built some models, and I made a drawing of what I envisioned happening. And when we started working on it, the first thing we did is to throw the drawings away and put the model away and just allow the stonework to determine what was needed there. And there was George’s amazing ability to look at this beautiful stonework and be able to put it together in a very clever and functional way.

Ana De Almeida Amaral: With an attention to the beautifully carved granite slabs and to the tides… the Wave Organ rose from the rocks on the jetty in 1986. The Wave Organ is a magical integration of the natural and constructed world. It’s an art piece that sits at the center of many intersections — between the sea and moon and between science and art. And here, you get to be an audience to all of it. But before I left the Wave Organ, I had to ask Ken, the educator from the Exploratorium, the question we are all waiting for: When is the best time to hear the Wave Organ?

Ken Finn: Definitely check the tides. And I think that visiting the Wave Organ at high tide is the best time. And it’s definitely a lot more enjoyable to be there when the tide is high, and it’s making some tones that are much more easy for us to hear.

Ana De Almeida Amaral: But, in case you are not able to make it out to the Wave Organ at high tide — we’ll bring it to you. Here’s 30 seconds of oceanic art.

[Sounds from the Wave Organ]

Olivia Allen-Price: That was KQED’s Ana De Almeida Amaral.

Thanks to Robbie Rock for asking the question and to Bill Fontana for letting us share a piece of his sonic art.

The Bay Curious team is taking a little breather next week, so we won’t have a new episode.

But, we did create a kid-friendly Spotify playlist with some of our greatest hits from over the years. If you’ve got travel plans and need to fill some time — check it out! We’ll drop a link in our show notes. We’ll be back in your feeds on Dec. 5.

Gift-buying season is on the way, and I know, at least for some of you, it’s been here since Halloween, so I’d love to humbly suggest you consider giving the Bay Curious book this year. It’s chock full of history, culture, fun facts and more all about the San Francisco Bay Area. You can find it at most local bookstores and all the big online retailers. If audiobooks are more your jam, we’ve got one of those too. Learn more at KQED.org/BayCuriousBook.

Bay Curious is made in San Francisco by Ana De Almeida Amaral, Amanda Font, Christopher Beale and me, Olivia Allen-Price.

With additional support from Jen Chien, Katie Sprenger, Maha Sanad, Chris Hambrick, Holly Kernan, Chris Egusa and the whole KQED family.