Across the Sierra Nevada, this winter has been a tale of ups and downs, wets and dry and cold and warm temperatures. Now, the snowpack looks to be back on track for a normal year, with more storms on the way.

The mountain range received an early-season dusting in August, several feet of snow in December, a relatively dry January and several storms in February. With less than a month of winter left, the Sierra snowpack is at 73% of the April 1 average, which is closely watched by water managers to understand how much they can rely on snowmelt to recharge watersheds and reservoirs for the remainder of the year.

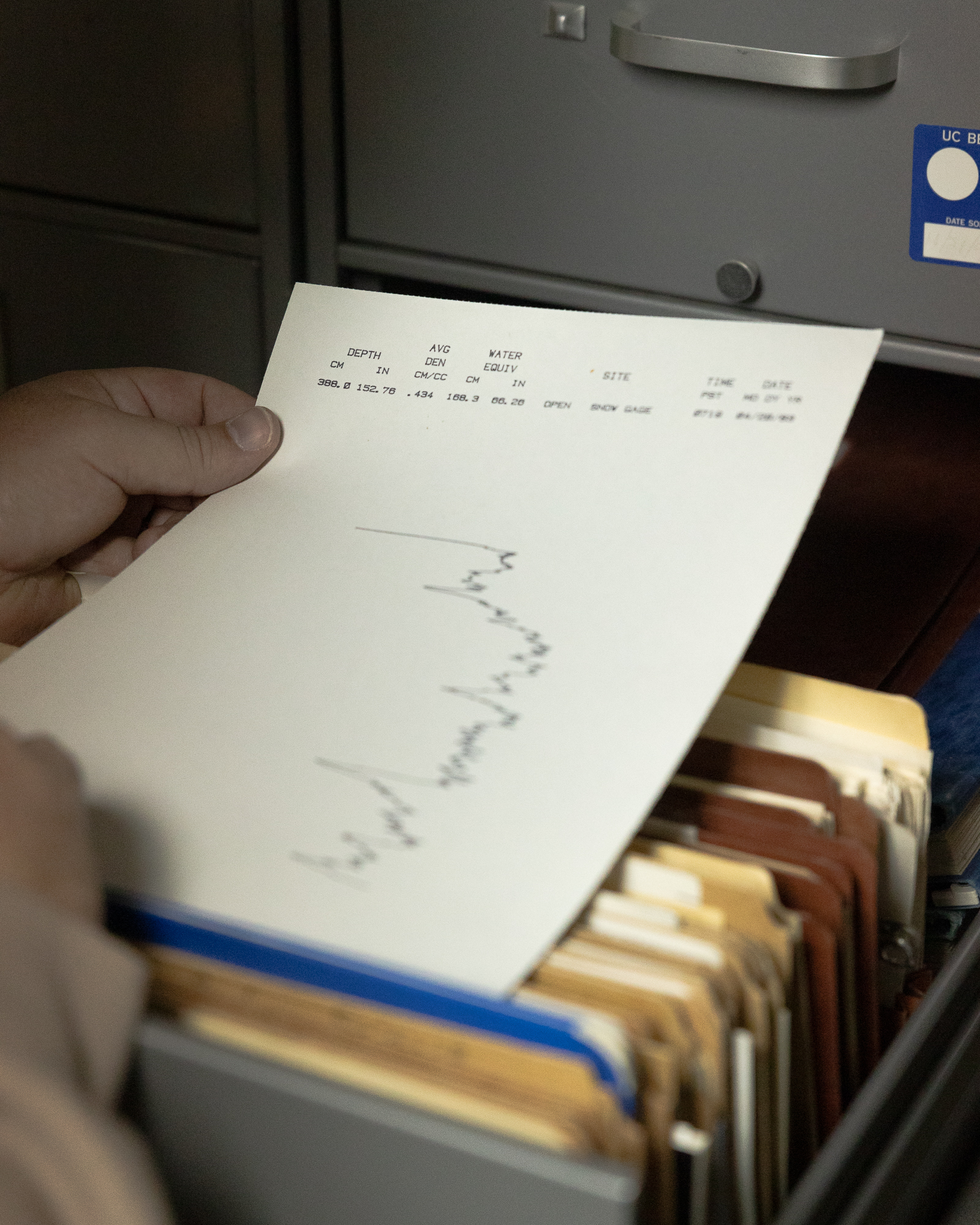

“We’re roughly at average again, which is really good news,” said Andrew Schwartz, lead scientist at the UC Berkeley Central Sierra Snow Lab. “Most, if not all, of our really big water storage reservoirs are above capacity at this point. To have an average snowpack to help maintain those levels is fantastic.”