Bobba is also one of many DOGE employees who, according to several federal judges, were inappropriately given that access in violation of privacy laws and without proper training to handle the personally identifiable information the agencies collect.

In one order last week blocking DOGE’s access to Social Security data, U.S. District Judge Ellen Lipton Hollander of Maryland said the government “never identified or articulated even a single reason for which the DOGE Team needs unlimited access to SSA’s entire record systems, thereby exposing personal, confidential, sensitive, and private information that millions of Americans entrusted to their government.”

Instead of a more narrow approach to data access and work to “modernize the system and uncover fraud,” Hollander wrote that DOGE’s unprecedented access to protected data “is tantamount to hitting a fly with a sledgehammer.”

An NPR review of thousands of pages of records across more than a dozen lawsuits in federal court finds an alarming pattern across agencies, where DOGE has given conflicting information about what data it has accessed, who has that access, and most importantly — why.

‘No need to know’

When President Trump signed an order creating the DOGE initiative, it directed agencies to create dedicated teams that would have “full and prompt access to all unclassified agency records, software systems, and IT systems” that would also “adhere to rigorous data protection standards.”

Numerous court filings and affidavits paint a picture of agencies rushing to give DOGE access without accompanying rigor of protecting data or documenting the scope of its work.

On Monday, a federal judge in Maryland temporarily halted DOGE from accessing data of millions of union members in a lawsuit against the Office of Personnel Management, the Treasury Department and Education Department after finding the agencies shared private information with DOGE affiliates “who had no need to know the vast amount of sensitive personal information to which they were granted access.”

“No matter how important or urgent the President’s DOGE agenda may be, federal agencies must execute it in accordance with the law,” Judge Deborah L. Boardman wrote. “That likely did not happen in this case.”

In the Social Security Administration lawsuit, Hollander found several DOGE staffers “were granted access to SSA systems before their background checks were completed or their inter-agency detail agreements were finalized.”

One of those is Bobba, who was given access to the master data warehouse at SSA that includes the Master Beneficiary Record, Supplemental Security Record and Numident files containing “extensive information about anyone with a social security number,” according to filings in the case.

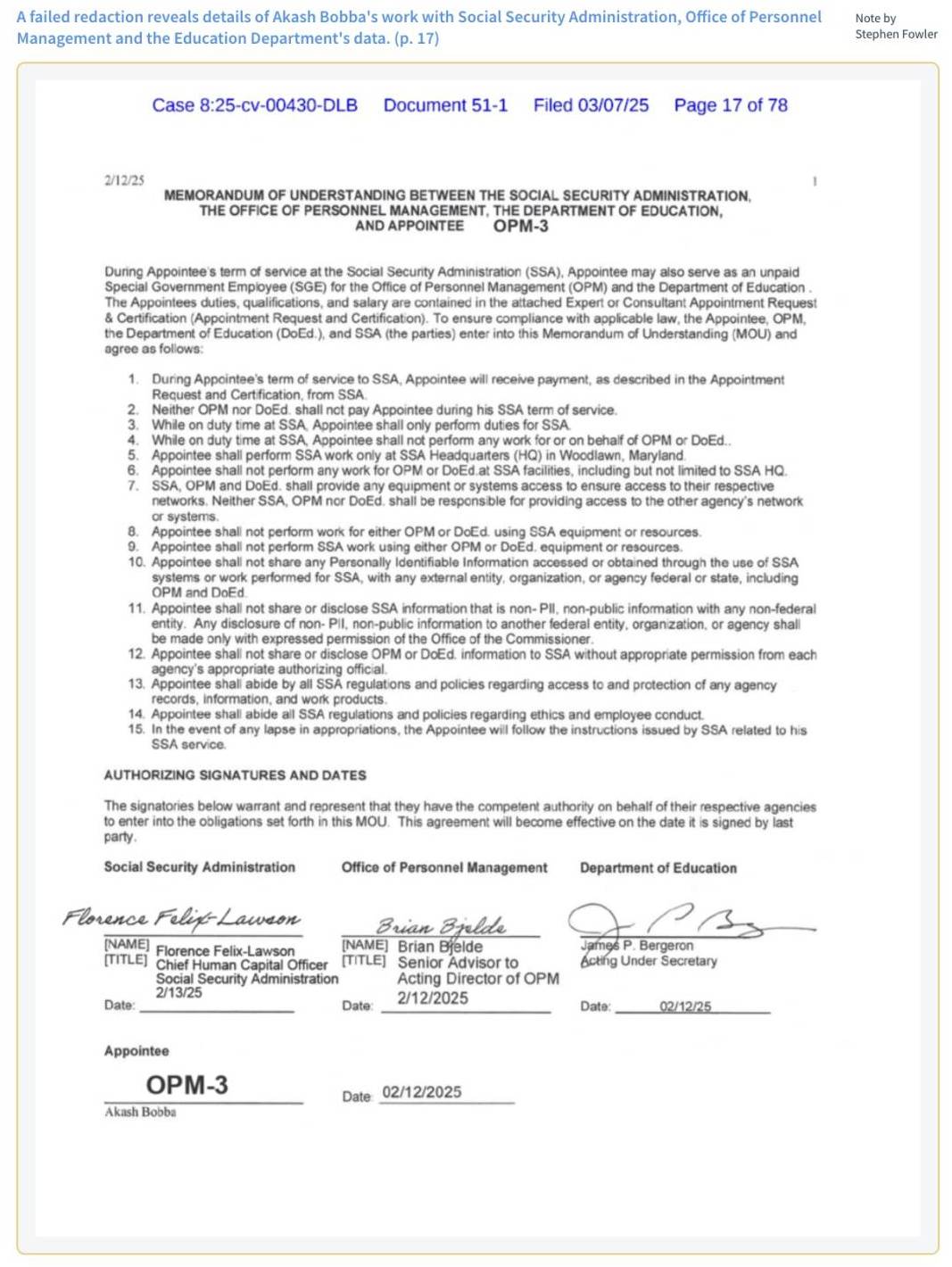

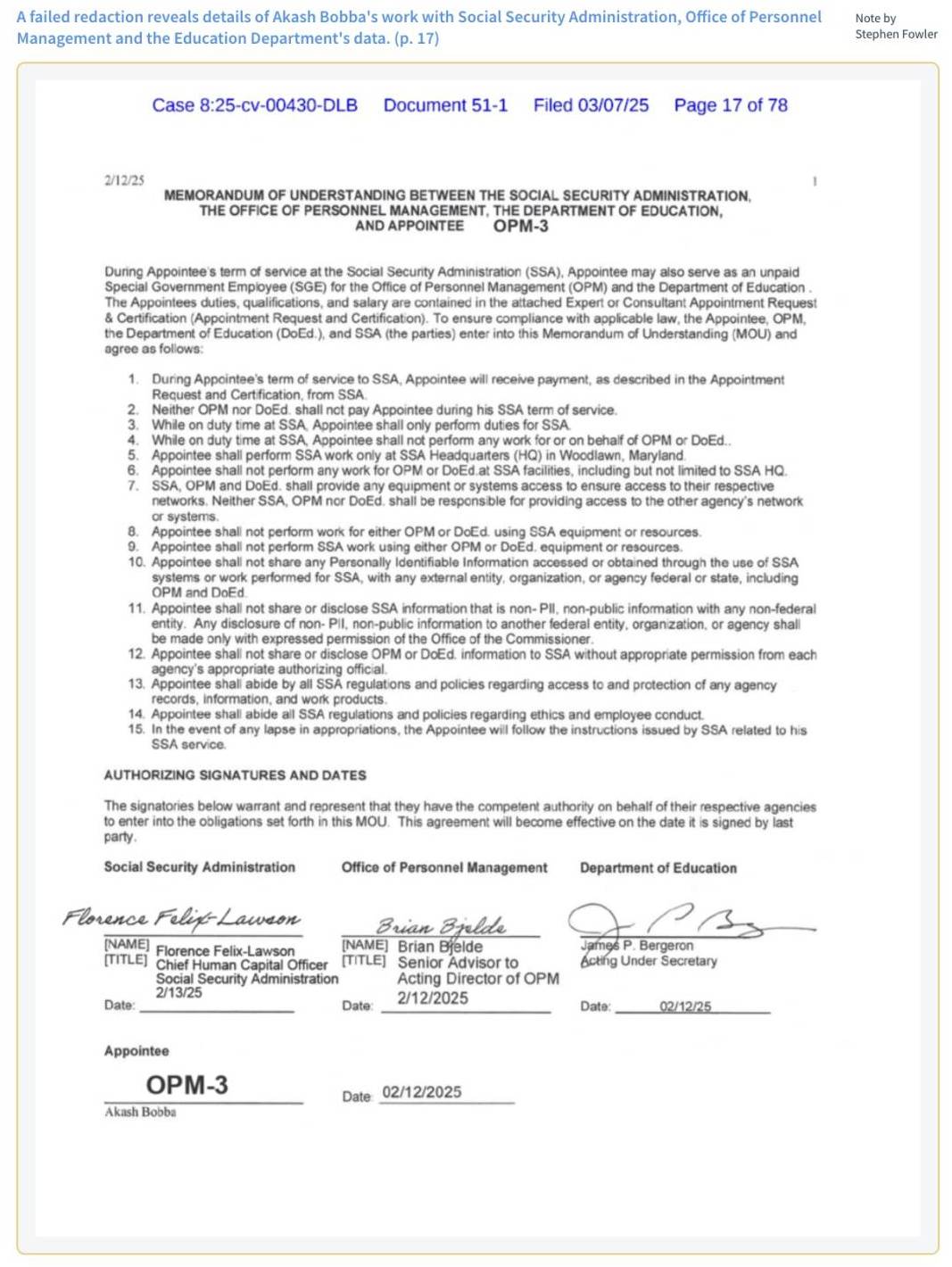

According to a memorandum of understanding detailing Bobba’s work with SSA, the Office of Personnel Management and Education Department that was improperly redacted by OPM, Bobba agreed to do any work on Social Security data from the agency headquarters.

But an affidavit from former SSA chief of staff Tiffany Flick said that Bobba was working off-site from OPM where other people “may have also had access to this protected information,” Flick wrote.

Not even lawyers for the government can account for when and how DOGE staffers received access to sensitive databases. In a Labor Department lawsuit, Judge John D. Bates notes that “defendants themselves acknowledge inconsistencies across their evidence” regarding DOGE.

Marko Elez, a DOGE employee who resigned from his post at the Treasury Department in early February after racist social media posts resurfaced, “sent an email with a spreadsheet containing PII to two United States General Services Administration officials,” according to an audit (PDF) of his email account submitted in one court filing.

Government lawyers said Elez was “erroneously” and “mistakenly” given the ability to change data on Treasury’s Secure Payment System, which a judge said demonstrates DOGE access was “rushed and undertaken by political pressure.”

In a ruling blocking DOGE access to Treasury systems, Judge Jeannette Vargas warned that “a real possibility exists that sensitive information has already been shared outside of the Treasury Department, in potential violation of federal law.”

Congress warned against this — a half-century ago

When Congress passed the Privacy Act of 1974, lawmakers expressed concerns about personal information amassed in digital databases by the “omnivorous fact collectors” of federal agencies.

During the debate about the bill, Arizona Republican Sen. Barry Goldwater was worried about the possibility “that every detail of our personal lives can be assembled instantly for use by a single bureaucrat or institution.”