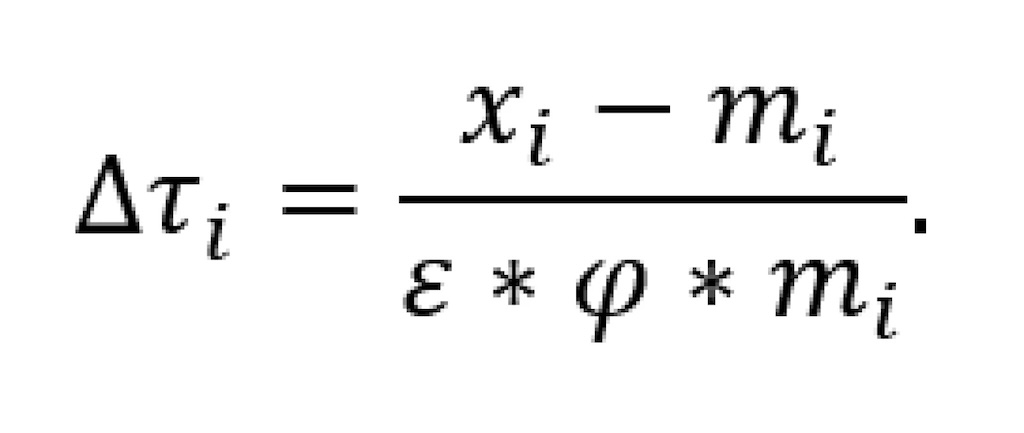

There are a couple of major assumptions in Trump’s math. The biggest assumption involves how much the tariffs would cause prices to go up. Here, the administration makes an eyebrow-raising admission: It guesses that for every 10% hike in tariffs, there will be a 2.5% increase in prices.

Translation: Trump’s economists think that about a quarter of his tariffs will be passed onto American consumers in the form of higher prices.

Going back to the China example, here’s how it would all play out. According to Trump’s math, the 67% tariff on Chinese products would cause prices of those products to go up by 16.75%.

By coincidence, the administration also assumes that for every 10% increase in the price of foreign products, there will be a 40% decrease in how much Americans buy. (This is on the higher but still reasonable end of what mainstream economists believe.) So, faced with 16.75% higher prices, Trump expects Americans to decrease their purchases by four times that amount. Which brings us back to 67%.

In other words, a 67% tariff on Chinese products would reduce demand for Chinese products by … also 67%. So if Americans are currently buying $439 billion worth of Chinese products each year, Trump’s economists expect that the new tariffs will reduce that spending by $294 billion — which would close the trade deficit. At least in theory.

What’s wrong with Trump’s tariff math?

Certainly these new tariffs are not “reciprocal” tariffs. But the math behind them is not wholly invented or nonsensical, despite what some online have claimed.

In fact, for possibly the first time ever, the administration is explicitly acknowledging some of the basic economic logic of tariffs. Tariffs do raise prices. And higher prices do cause people to buy less stuff. And if Americans buy less foreign stuff, then America’s trade deficit with other countries will narrow.

But that’s not to say that any of Trump’s tariff calculations arrive at the right answer. For one, these are very rough, back-of-the-envelope calculations. As laid out, this formula treats every trading partner, every good and every industry the same. Bananas, oil, clothing, computers or cars — it doesn’t matter what a country sends to the U.S.

More importantly, the formula hinges on a big assumption about how much tariffs will raise prices. Trump’s math assumes that only a quarter of the tariffs would be passed onto American consumers in the form of higher prices. But economists who have studied Trump’s tariffs in 2018 — on steel and aluminum and various products from China — calculate that almost all of those tariffs (PDF) ended up being passed onto Americans.

Aside from that, Trump’s tariff math also ignores the broader economic consequences of these sweeping new tariffs. They will have an effect on the overall American economy. They will influence exchange rates. And they will likely provoke retaliatory tariffs from other countries.

So, will Trump’s new tariffs actually close the trade deficit? Maybe, maybe not. But finally, at least, the administration has shown its work. And according to their calculations, raising prices and closing the trade deficit is what these tariffs are designed to do.