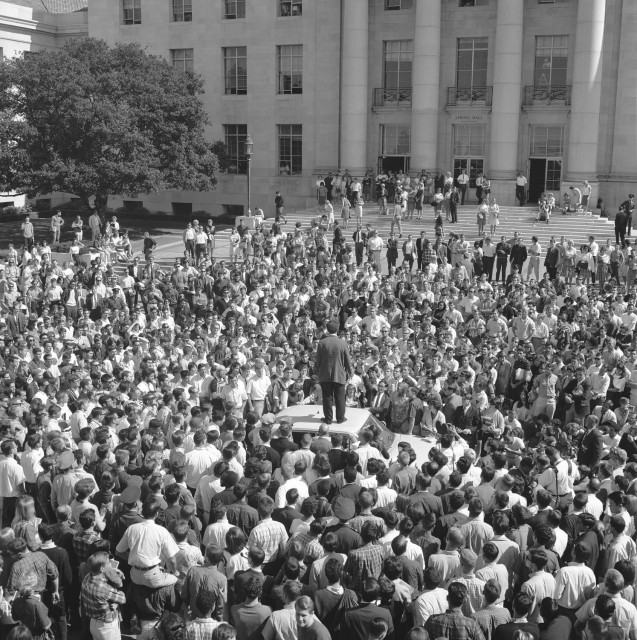

On Forum, Weinberg recounted how he and other young activists in fall 1964 had reached a boiling point over the university administration’s ban on political speech and campus activism. Weinberg defied the ban and set up a table to distribute civil rights literature. He soon found himself under arrest and hauled into a police car. Students, realizing what happened, surrounded the police car. Weinberg spent 33 hours inside as activists turned the car into a podium for what would become a historic rally for free speech.

The image of Mario Savio standing atop the car in his blazer and stocking feet (so as not to damage the roof) as he demanded “no arbitrary restrictions of free speech of any kind on this campus” is iconic -- but not just as a media artifact of '60s bravado. Robert Cohen, also a guest on the Forum program, wrote in "The Free Speech Movement: Reflections on Berkeley in the 1960s" that "what happened at Berkeley was an authentic political invention -- a new and complex mixture of issues, tactics, emotions, and setting that became the prototype for student protest throughout the decade. Nothing quite like it had ever before appeared in America.”

The show's guests focused on the movement's legacy after recalling the events of Oct. 1 and its aftermath, leading up to the occupation of Sproul Plaza on Dec. 2, the mass arrest of students on Dec. 3 and UC Berkeley Chancellor Clark Kerr’s speech upholding the university’s right to restrict speech -- culminating in the vote by the Academic Senate on Dec. 8, 1964, finally acceding to student demands and lifting all restrictions on speech. (You can listen to the complete episode here. The events are also chronicled on this timeline and in the documentary “Berkeley In the Sixties,” available to stream on Netflix.)

The Way It Was (And Is)

It is the connections from that time to the present that resonate, the guests said.

“I think it’s a mistake to think that all of this is past and ancient history,” Cohen said, mentioning the Occupy protests that swept the nation’s campuses and cities in 2011 as well as today's movement to stop climate change.

According to Goldberg, most people have a distorted idea that the FSM roared into history with thousands of activists at the ready. She recounted sitting at literature tables on Bancroft Way with a handful of other students as people walked by without a glance. “There’s a mythology that somehow we were different and these kids today are not as good as we were. That’s just baloney.”

Weinberg agreed. “Young people today are getting a bad rap,” he said. He denounced growing economic inequality, and said huge tuition hikes have made it necessary for students to work all the time to pay off their loans. “I think that’s coming to a head right now.”

As recently as 2011, riot police used batons to remove students and Occupy protesters from Sproul Plaza, described in a piece in The Atlantic as “the ground zero” of the FSM. The Academic Senate later condemned the police actions, and the administration backed down and apologized. Cohen noted the outrage was recognition that the Dec. 8, 1964 resolution, which said the content of speech should not be regulated, is still crucial.

Recent comments by UC Berkeley Chancellor Nicholas Dirks might indicate that the debate over free speech issues is far from over. His Sept. 5 email to faculty, staff and students, titled “Civility and Free Speech,” caused an uproar because he seemed to qualify what constituted acceptable speech, writing: "We can only exercise our right to free speech insofar as we feel safe and respected in doing so, and this in turn requires that people treat each other with civility.”

Critics of Dirks’ email noted that civility is a specious criterion for protecting speech; They say that some spoken dissent is by definition going to be considered uncivil by authorities who generally have the power to regulate it, such as the university administration or the government.

A few days later Dirks sought to clarify his comments, which he said were not meant in any sense to advocate squelching dissent: “In invoking my hope that commitments to civility and to freedom of speech can complement each other, I did not mean to suggest any constraint on freedom of speech, nor did I mean to compromise in any way our commitment to academic freedom, as defined both by this campus and the American Association of University Professors.”