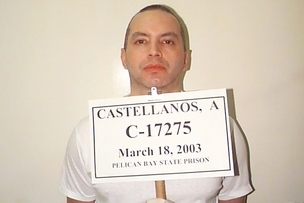

Castellanos was convicted of murder in Los Angeles County in 1979 and sentenced to 26 years to life. But his life of crime flourished behind bars, according to prison records.

As an inmate, Castellanos’ disciplinary record includes six stabbings and various drug violations. In 1990, he was sent to Pelican Bay’s Security Housing Unit after corrections officials identified him as a member of the Mexican Mafia prison gang.

In spite of Pelican Bay’s harsh conditions, authorities allege Castellanos continued to command gang members on the street through edicts smuggled out of prison on tiny scraps of paper known as “kites.”

According to a 2007 federal indictment, Castellanos guided a Latino street gang known as F13 as it launched a turf battle against African American rivals. The action triggered a wave of racial violence against African Americans living in the Florence-Firestone area north of Watts, according to court documents. More than 20 people were killed.

"I was just amazed that an individual who no one has seen for generations was able to control the violence and illegal criminal activity of an area that he hasn't been to in more than three decades," said Peter Hernandez, an assistant U.S. attorney for California's Central District.

Federal prosecutors eventually indicted 104 suspects in the case, but not Castellanos. He already was serving a life sentence, and the government concluded it was safer to keep Castellanos in isolation and not pull him out of Pelican Bay for court hearings, which would have been required had he been indicted.

"It was important that … Castellanos not be let out, because he holds sway over gang members to do things they would otherwise not want to do," Hernandez said.

Since 2006, Castellanos has been housed in a special section of Pelican Bay’s Security Housing Unit that is reserved for inmates deemed influential gang leaders.

But that didn’t stop him and three other inmates from organizing a three-week hunger strike to demand better conditions and changes in department policy.

During a recent media tour, Pelican Bay acting Warden Greg Lewis claimed the four hunger strike leaders, including Castellanos, were in the upper echelons of major prison gangs and continued to pose a serious security threat. Lewis said the men are “intelligent, very manipulative and possess the intellect to orchestrate what they did.”

While prisoner rights advocates concede that some inmates should be segregated from the regular prison population if they are violent or directly involved in criminal conspiracies, they say the actual number of offenders who fit that criteria is very small.

“The California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation always picks the worst-case scenario and uses it as the norm,” said Carol Strickman, a staff attorney at Legal Services for Prisoners with Children.

Not all the inmates locked in the Security Housing Unit are accused of being gang bosses.

Ernesto Lira was serving a sentence for drug possession in a low-security prison when he was sent to Pelican Bay for an “indeterminate” term. Authorities contended Lira was an associate of a violent Latino group known as Nuestra Raza.

But Lira was not accused of doing anything tangible for the group. The key piece of evidence against him was a drawing found in his locker that allegedly contained gang symbols.

"My first two months, it was hard to get used to the fact that I'm going to be here," Lira said. "I looked and thought, maybe in a month or two, they'll realize that this is all a mistake and kick me out of here."

Lira said officials offered him a quick way out of the special unit: He could debrief, or snitch, on other gang members. But as a judge later determined, Lira couldn't do that because he wasn't a member of any gang. He wasn't released from isolation until his release from prison eight years later.

Lira eventually won a judgment in U.S. District Court against the Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation, in part for psychological damage he suffered while locked in isolation.

"In Ernesto's case, I think it's very emblematic of the fact that people can be placed in solitary confinement for the littlest of reasons: for having a drawing, for having an address in an address book, without confirming or denying whether that address was used for furthering gang activity," said Charles Carbone, an attorney who has represented dozens of Pelican Bay inmates.

Corrections officials declined to discuss Lira's case. But they now are considering changes that, if fully implemented, would keep inmates like Lira out of isolation units.

Under a plan being reviewed by department officials, an inmate would have to commit a specific offense for a gang or be involved in an active conspiracy to qualify for placement in one of the state’s four Security Housing Units.

Also under consideration are incentives to encourage inmates to work their way out of the units through better behavior. This is known as a stepdown program, which usually does not require inmates to debrief.

Former prison gang leaders like Rene Enriquez say the plan could work. Enriquez was a top leader in the Mexican Mafia who spent 10 years in Pelican Bay’s Security Housing Unit before deciding to leave the gang.

"That's a wonderful concept," Enriquez said. "It would have saved me a whole lot of grief. It might have taken me off the hit list."

Enriquez’s 2004 debriefing video has attracted more than 600,000 hits on YouTube. Since then, Enriquez has cooperated from behind bars in several high-level gang prosecutions.

He said the department should stay tough on gang leaders, but it should take a more nuanced approach toward others, including offering another path out of the isolation units that doesn't include debriefing.

"Fifty percent of the members of the Mexican Mafia would gravitate towards dropping out if it was less traumatic … and didn’t require snitching," he said.

Corrections officials are expecting to have a set of policy proposals ready for stakeholder review by late October. But they emphasize two things: Any big changes could take many months to hammer out, and the department will continue to use special segregation units for inmates who pose a major security threat.