Wong says that although disabled people are a part of every community, white supremacy upholds ableism and tries to regulate what it means to be “normal.” “Everything about normal behavior is very much based on a nondisabled [person],” says Wong. “So when people are different, they navigate through the world [and], they communicate differently. That’s when these points of violence often happen.” For Wong, systems that incarcerate and trap people uphold this disciplining, which is often racialized. For example, Wong points to the many Black and disabled people killed by police and how often, their disability is ignored.

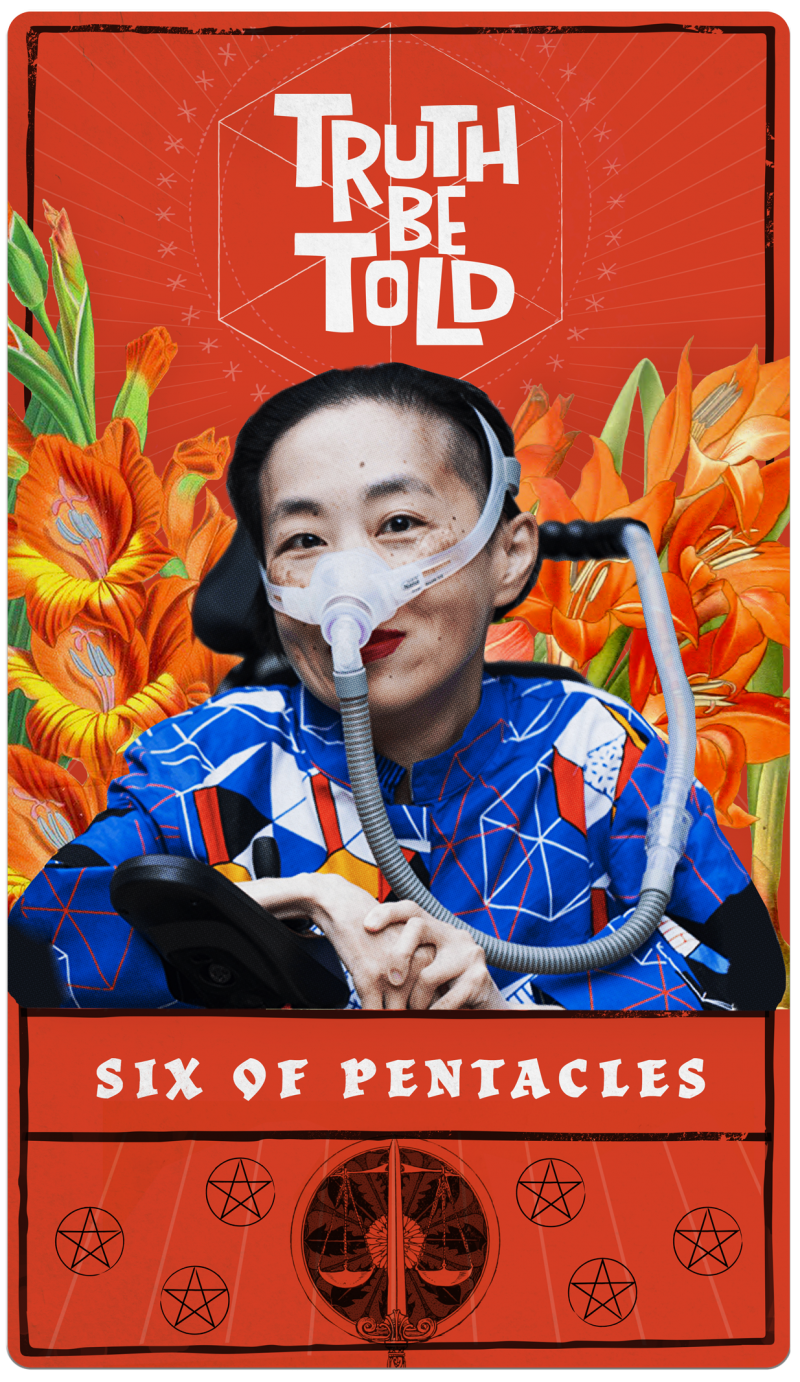

Wong is elevating the voices of disabled people in such a rich way across all platforms. That is why we chose her as this week’s Wise One.

This week’s question came from an anonymous listener: “I have a rare brain condition called Chiari Malformation. And I don’t know what ways I can educate my friends and family without making them feel like I’m shoving information down their throats. Help, please.”

Chiari Malformation is a condition where brain tissue extends into the spinal canal. There are various types of Chiari Malformation but common symptoms are muscle weakness, lack of balance or abnormal reflexes, nerve problems, difficulty swallowing and sleep apnea. Long-term impacts can be paralysis, damage to muscles or nerves, pain and a pocket of spinal fluid in the spinal cord or brain stem.

“One of the biggest challenges for people with invisible disabilities is the fact that their families and friends can’t recognize how serious these are,” says Wong. “Or, oftentimes they don’t believe the disability and say, ‘You look healthy,’ or ‘You look fine.’ I think that’s part of the challenge.” Wong says this is a big source of emotional labor that disabled people have to do all the time. “It’s always like, ‘No, actually this is really difficult’ or ‘No, what you see is not obvious.’”

Here are Alice Wong’s tips:

Tip #1 Educate folks in smaller doses

Wong believes long lectures don’t work but preparing some information beforehand may be useful. Her advice is to prepare a sheet of information in a Google Doc describing your disability or condition. Add things you think they should know about and share the doc. Wong says you can send it with a message that says something like, “Hey, if you want to learn more about what I’m going through and just some of the basics, here it is.” This way, Wong says, you don’t have to constantly repeat yourself and can prevent exhaustion. Another option is when you are having a bad day related to your disability, sharing with a loved one what is happening. Lastly, Wong suggests being selective about when you feel you can take on the responsibility of explaining because it can be draining.

Tip #2 Gently push back

Because educating people on your disability can be emotionally exhausting, Wong says you can gently push back. “The information is already out there for the questions that I receive. So I would invite them to do the work because I also feel like this is not my responsibility.”

Tip #3 Be honest about how their actions are impacting you

“You know there are times where I felt hurt or excluded by friends or family members who are not disabled,” says Wong. “And it’s just so frustrating all the time to try to educate people. So at least one of the ways to try to reach people is to really be honest about how their actions are impacting you. Maybe start with that first and then go with the educational piece.” Some suggested language: ‘What you said to me, you may not realize it, but it was really painful and this is why.’”

Wong says you can also try to get loved ones to understand why they should learn more. She cautions that this is a very gradual process and won’t happen overnight. However, being honest and vulnerable with loved ones is really important.

“Sometimes disabled or chronically ill people are not at a place yet where they feel permission or okay in saying, ‘This is what I need right now. And this may change in the future, but at this point in time, I need you all to back off,’ or ‘I need you all to stop making assumptions,’ or ‘I need you all to stop feeling sorry for me.”

Wong says there is a fear of hearing family and friends’ responses but part of the process is accepting that loved ones will understand. “That’s one thing about being disabled, it’s almost like a filter where you really see the people who really have your back,” Wong says. “Your relationship with them may change, but if they really care about you they’re going to be with you or just learn to adjust.” Wong also advises letting loved ones know that you are there for them in their learning process.

Episode transcript can be found here.

Episode Guests:

Alice Wong (she/her) is a disabled activist, media maker, and consultant based in San Francisco.

Recommended Reading:

Disability Visibility: First Person Stories from the 21st Century, edited by Alice Wong

Discussion guide and plain language summary of the book.

I’m Disabled & I Refuse To Be Your Inspiration by Jillian Mercado

Black Disabled Lives Matter: We Can’t Erase Disability in #BLM by Sarah Kim

Resistance and Hope: Essays by Disabled People, edited by Alice Wong

Care Work: Dreaming Disability Justice by Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha

Too Late to Die Young: Nearly True Tales from a Life by Harriet McBryde Johnson

Crip Theory: Cultural Signs of Queerness and Disability by Robert McRuer, Michael Bérubé

Bodymap by Leah Lakshmi Piepzna-Samarasinha

The Cancer Journals by Audre Lorde

The Diary of Frida Kahlo: An Intimate Self-Portrait by Frida Kahlo, Carlos Fuentes, Sarah M. Lowe

Exile and Pride: Disability, Queerness, and Liberation by Eli Clare

Blackness and Disability: Critical Examinations and Cultural Interventions, edited by Christopher Bells

The Ultimate Guide to Sex and Disability: For All of Us Who Live with Disabilities, Chronic Pain, and Illness

by Miriam Kaufman, Cory Silverberg, Fran Odette

The body is not an apology blog

10 Principles of Disability Justice by Sins Invalid