In protest, Mendoza and 2,000 allies marched to City Hall to draw attention to the police brutality. Unconvinced that action was being taken to tackle overzealous law enforcement quickly enough, she helped set up San Jose’s Community Alert Patrol in 1968, alongside her neighbors, including members of the clergy and Tom Ferrito, who went on to become Mayor of Los Gatos in 1980. It was essentially a sort of Neighborhood Watch—only, instead of keeping an eye out for the activities of criminals, volunteers kept watch over the police instead.

“About 200 people were involved in it,” activist Fred Hirsch explained in a 2015 talk. “We put out three or four cars each weekend night and holiday occasions. We’d have three people in the car. We did our best to get complete diversity among the people in terms of ethnicity… We also monitored community events, and we were not at all immune to the actions of the police department.”

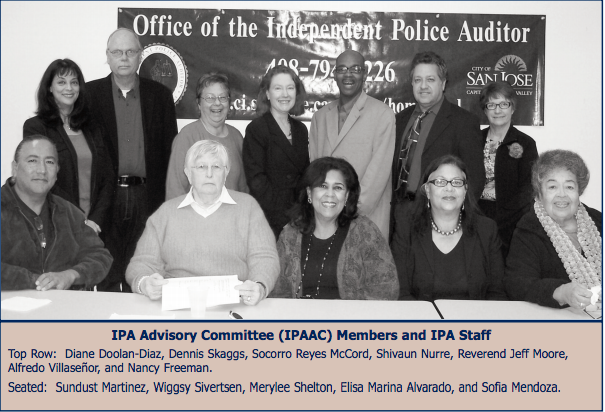

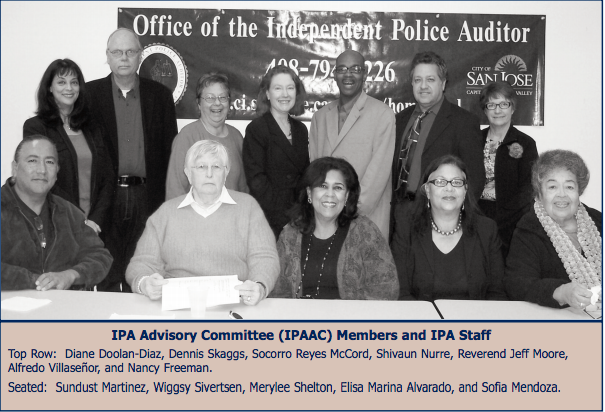

Mendoza’s scrutiny of law enforcement continued for the rest of her life. Here she is, in 2009, acting as a member of the Independent Police Auditor Advisory Committee—an organization that came into being, in part, because of her campaigning.

By the 1970s, Mendoza had become a much-beloved force in her community. She battled San Jose’s Redevelopment Agency when her neighbors were suffering mass evictions. She was active in assisting Chilean refugees settle in the city, as they escaped the military coup of Augusto Pinochet. She was active in getting East San Jose its first health clinics. She led the Mexican American community in fighting for voting rights. Like her neighbor César Chávez, and her father before her, she also became involved in farmworker unionization.

Above all else, Mendoza’s entire life was spent in service to the community. She founded United People Arriba, an organization that helped unify and galvanize activists in their own communities. Later in her life, she served as a social worker, a member of the board of directors at the Community Child Care Council, and a community organizer for the Family Service Association of Santa Clara County.

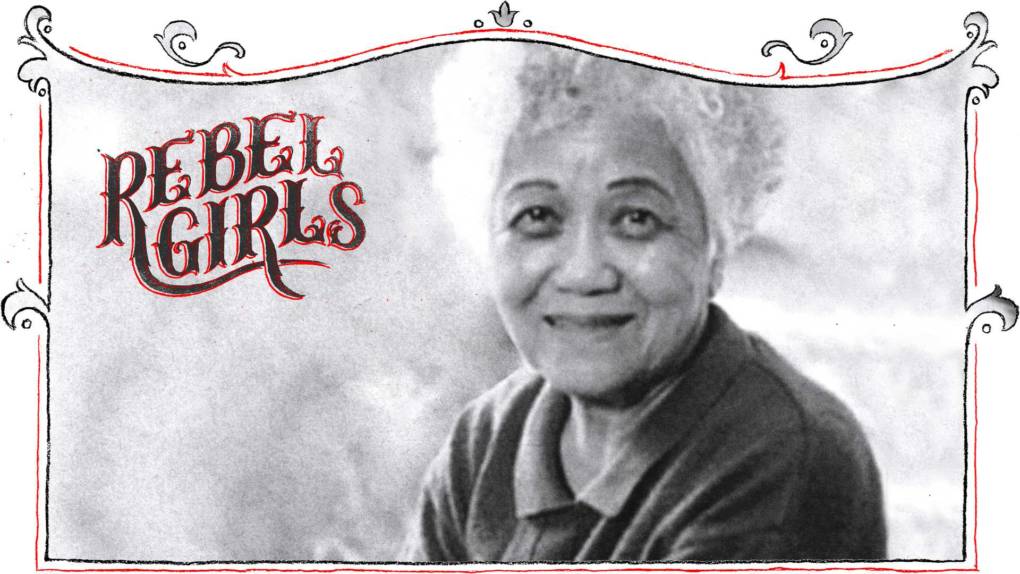

Throughout it all, Mendoza retained an impressive sense of humility. After her death in 2015, at the age of 80, Nannette Regua, a history teacher she had mentored, said of Mendoza: “She never said, ‘I did this.’ She never said, ‘I led these community organizers.’ It was always, ‘We.’”

For stories on other Rebel Girls from Bay Area History, click here.