Netflix is hungry, and it's got its eye on a juicy slice of interactivity.

The streaming service started its originals business with prestige dramas and comedies. But its appetite increases, and now it also wants to be your source for holiday schlock, baking competitions, home renovation shows, documentaries, animation, stand-up specials, and romantic comedies. And it's looking for new areas that it can own, new ways it can make itself essential, new worlds it can dominate. A new film that can follow a variety of paths depending on choices made by the viewer—a film that's almost a game—is the next direction it would like to stomp its giant feet.

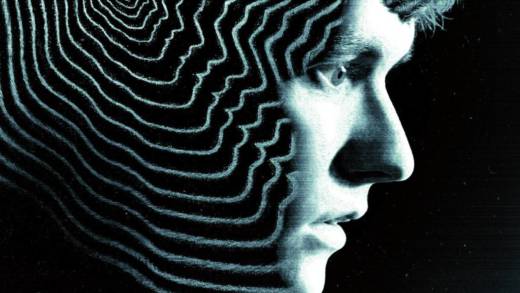

Black Mirror, a science fiction anthology series focused on the horrors of technology, was originally on British television. Now, Netflix makes it directly for its streaming service. On Friday, Black Mirror released its latest installment, called Black Mirror: Bandersnatch. Set in 1984, it's about a young programmer named Stefan working on a game adaptation of a famous "choose your own adventure" book. For those who aren't familiar, CYOA books (which really existed) are books where at certain points, the story asks you to make a decision. Something like, "If you pick up the stick, turn to page 49. If you leave the stick on the ground, turn to page 51." And you would follow the story from there. CYOA was an elementary, low-tech version of interactivity, long before today's complex open-world games were available.

The innovation of Bandersnatch itself is that it functions similarly. While you're watching the film, on Netflix, on your television, a choice will come up on the screen, and you'll use your remote (or your computer or finger or whatever) to choose the option you want. The first choice, for instance, is what Stefan will have for breakfast from the two cereals his father shows him. Whichever you choose, that's what you see his father hand him. As you can imagine, the choices grow more significant than that later in the film.

It would have been good to see this technology demonstrated on a stronger story. While it obviously makes sense for Stefan to be developing a CYOA game inside a Netflix CYOA movie about him—that's kind of the joke—you don't really learn enough about who he is to care about him. Sure, he's getting angry and wondering if he's losing it while he works on his game, but that's pretty elementary "isolated artist who might go mad" stuff, and it doesn't really hold up a narrative on its own.

9(MDAxOTAwOTE4MDEyMTkxMDAzNjczZDljZA004))