A passenger plane disappears mysteriously. The government is caught lying to us. Religious fanaticism dominates the airwaves. Anti-Western proclamations from Soviet stalwarts fill the newspapers. Russia invades a neighboring sovereign country. Approval ratings continue to plummet for the US president, a Democrat. Families across America gather on their sofas to watch the latest episode of Cosmos. This can only mean one thing: we have arrived in 1980!

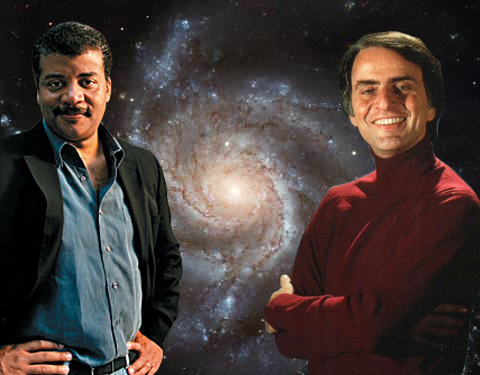

Or maybe 2014. Starting a few weeks ago, Cosmos has been airing Sunday nights on FOX (and streaming online). This is not your parent's dusty old Cosmos. This is a shiny new reboot hosted by Neil deGrasse Tyson. Soft-focus skyscapes are replaced with crisp 3D asteroids, and dramatic cartoon sequences fill in for historical reenactments. But the biggest difference may be the politics. The original series packed a peaceful message of nuclear non-proliferation. Sagan brilliantly connected the possibility of extra-terrestrial life, of communicating with it and perhaps one day meeting it, to the necessity for nuclear disarmament. Couched in meditations on extra-terrestrial contact, Sagan's simplifying, awe-inspiring description of the big picture helped make him an icon of an expanded cosmic view.

Fast forward to a new generation, a new existential crisis. For the last decade, action-packed edutainment like History Channel's The Universe: End of Earth and Sex In Space have narrativized our dangerous and erotic existence. Tyson's Cosmos struggles to find an identity separate from those tropes while still entertaining viewers. It's hard for me to fairly compare the awe I felt watching the original series as a very young kid, and the near-permanent state of eye rolling I experienced during the first episode. The second episode was much better. But it left me wondering: Can Neil deGrasse Tyson be the Carl Sagan for our times?

Or maybe a better question is: Does anyone remember Carl Sagan? In case you don't, here's a quick run-down. Carl Sagan was an accomplished astronomer, and a professor at Cornell. He was also one of the greatest communicators of science in the modern era. Sagan pioneered the search for extra-terrestrial intelligence in a time when E.T. communication was a given; all we had to do was pick up the phone. His groundbreaking Cosmos series, which broadcast on PBS in 1980, explained to the rest of us just how big and crazy and small and hard to fathom everything really is.

Cosmos arrived at the start of the cynical Reagan years, but it was a product of the previous era. Scientific progress was sill in ascent, and a New Age zeitgeist permeated our culture. Carl Sagan lived in that era of progress, believing that government policy could be influenced by reason, and that the respectability of scientific fact knew no peer. In those days, the scientific community and much of the public rallied around the greatest threat to life on Earth: a nuclear winter.