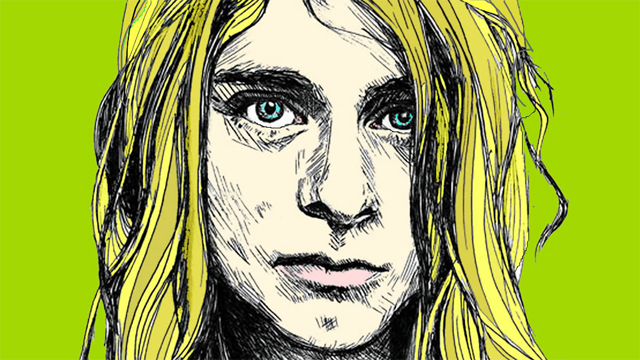

On April 8, 1994, the body of Kurt Cobain was found. It is estimated that he died three days before on April 5. The 20th anniversary of his death was widely commemorated, but the important day, the day we actually remember, is the day we found out. Was Cobain our last great rock star? Or was he in the right place at the right time for us to cast him in that role?

Numerous factors converged to define that particular era. Rock had arguably run its course. Grunge and college rock were like a dose of viagra in the Autumn years. Dubiously marketed as "alternative," the totalizing commodification of punk rebellion kicked into high gear. Nevermind pushed Michael Jackson's Dangerous out of the Billboard number one spot. Cobain was widely perceived as rock's savior, embodying the angst of the time; this is a role he rejected, and the drama of his rejection further cemented the title. Cobain hated the attention, and felt that the pressure destroyed his creative process, and ruined his passion for the music. Our adoration drove him to ruin.

In 8th grade, I came across a writeup of Nirvana's Bleach in Thrasher magazine, which the reviewer dismissed as more of the same crunchy guitar sound from Seattle. Not knowing what that was, and not knowing any better, I took the review at its word, and moved on to news of a new Anthrax album. This was the early '90s, a cultural extension of the previous decade. Number one songs of the period were diluted simulacra of important subcultures -- glam rock wannabes like Extreme, family-approved R&B from NKOTB and Milli Vanilli, and something approximating rap by Vanilla Ice. (In this fraudulent environment, "Smells Like Teen Spirit" peaked at #6 on the Billboard Hot 100.) But audiences listening to college radio and MTV's 120 Minutes were growing steadily. These were the new cool kids, slumped in flannel and ripped jeans, instead of donning silk and pristine blue denim. Underground genres like grunge and hardcore were philosophically anti-fashion, and they came into the spotlight at the very moment fashion was at its worst. Nirvana looked like alternative music scenesters, those new arbiters of cool, the recently emerged, newly labeled Generation X.

One morning in 10th grade, Smells Like Teen Spirit echoed through the halls at the end of the morning announcements. The song had significant buzz since some friends had seen the video on 120 Minutes. But my family didn't have cable, so this was the first time I heard it; alternative culture officially administered by my high school. I thought the loud parts were cool. The quiet parts were kind of whatever. It was pretty good, but I didn't quite see the big deal. But in the battle between mainstream and underground music, this was the shot heard round the world. In the 2001 VH1 special "All Access: 25 Years of Punk", David Byrne recalled hearing "Smells Like Teen Spirit" and thinking the punk energy of his era had finally returned. Ian MacKaye responded in an interview that Byrne was part of a music industry that had ignored an entire decade of underground music, because those subcultures didn't want to participate in the mainstream.

A couple weeks after first hearing "Teen Spirit", I bought Nevermind on cassette, and was disappointed overall. With all the talk of Nirvana as the vanguard of the Seattle grunge scene, I was definitely expecting something heavier. Nevermind was what we called "weak." It wasn't a grunge album, and the flagship track was Cobain's attempt at writing a Pixies song. But it didn't quite sound like the Pixies either; Frank Black's self-aware humor was replaced with Cobain's self-conscious performative emoting. My naive teen self began to notice the discrepancy between how music was marketed and what music actually was.