General boating also takes place at Big Break estuary due to its accessibility to the rivers and sloughs of the Inland Coast.

Hiking

The Big Break Regional Trail, which runs along the southern edge of Big Break through the Ironhouse Sanitary District, provides access for hikers, bicyclists, and equestrians to the southeastern edge of the estuary. The trail connects to the northern end of the Marsh Creek Regional Trail, providing access to Brentwood and Oakley. The Marsh Creek Regional Trail connects to the Delta de Anza Regional Trail via West Cypress Road, providing access to Oakley, Brentwood, Antioch, Pittsburg, and Bay Point.

Delta Discovery Experience

This facility is in the planning phase and will be located in the area of the park accessible from Big Break Road. When complete, it will offer picnic and meadow areas, a shaded amphitheater, boat and kayak launch facilities, an interactive map of the Delta, and covered, outdoor use areas for interpretive and educational exhibits and programs highlighting the Delta, its ecosystems, and wildlife.

Special thanks to Mike Moran, Shelly Lewis and Isa Polt-Jones of the East Bay Regional Park District for assisting us on this project.

Robin Marks, Joshua Cassidy, Craig Rosa and Ron Wolf all contributed to this Exploration.

The Pacific Flyway: Busier than 580 at Rush Hour

At 5:30 on a Friday afternoon, our freeways are famously clogged with commuters. Many of those drivers, tapping out tunes on their dashboards, may not realize that the real traffic in the Bay Area is overhead. Each spring and fall, millions of birds make their way to and from our local estuaries, oceanside cliffs, and river deltas, bringing about a spectacle of nature that seems otherwise lost in our modern world.

At 5:30 on a Friday afternoon, our freeways are famously clogged with commuters. Many of those drivers, tapping out tunes on their dashboards, may not realize that the real traffic in the Bay Area is overhead. Each spring and fall, millions of birds make their way to and from our local estuaries, oceanside cliffs, and river deltas, bringing about a spectacle of nature that seems otherwise lost in our modern world.

And when it comes to tourism in the Bay Area, the number of avian visitors rivals that of human visitors over the course of the year. Both the coast and the inland valleys invite hundreds of bird species. Many of them spend long stretches of time here, while others merely pass through, on their way to places as close as the Salton Sea or as distant as Patagonia.

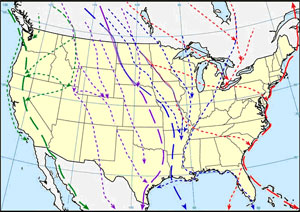

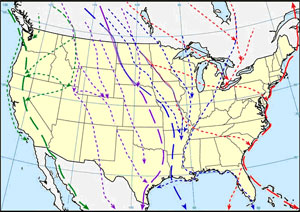

Migrating birds all over the world arrive and depart along predictable paths, which have been dubbed “flyways.” There are four major flyways in North America, stretching into South America: the Atlantic, Mississippi, Central, and Pacific.

See the four major flyways in North America

See the four major flyways in North America

Each flyway that passes through the United States even has its own council that works with state and federal wildlife agencies to protect birds and manage hunting regulations.

In California, the flyway has two “lanes,” one along the coast and the other that follows inland valleys. At the intersection of the Delta, the coast and the Central Valley, Big Break Regional Shoreline is an all-seasons crossroads for migrating birds, and draws all manner of shorebirds, raptors, and songbirds on their travels. On a good day, a birder can spot up to 60 species. Our avian visitors are a combination of birds wintering here from colder climes, and birds summering here who spend winter in Mexico or other points south. Spring migration antics peak from February through April, when visitors may be treated to meadowlarks, sparrows and dowitchers, among others, making their way out of town. Fall brings the spectacular return of Sandhill cranes showing off their six-foot wingspans. Among the summer tourists is the threatened Swainson’s hawk, a special guest at Big Break from June to August. Other good birding spots in the Bay Area include Elkhorn Slough, Don Edwards Wildlife Refuge, and Pt. Reyes, which is home to the Point Reyes Bird Observatory.

One fact that both amazes and helps bird researchers is that migrators tend to not only fly along the same route, but to actually return to very specific places. This means that if a particular bird is caught by a researcher’s net one year and then banded, there’s a good likelihood that same bird will end up in the same net the following year. This provides the opportunity for scientists to learn from observations made on specific birds year after year. Sometimes researchers also attach tracking devices as well as bands to the birds, allowing those birds’ movements to be followed in very detailed ways.

Some birds fly for weeks without stopping, others rest along the way. Some fly hundreds of miles, others fly thousands. No matter what their path, migration is a major effort that requires energy and time. Why do birds bother? It turns out that traversing all those miles has a real advantage when it comes to daylight. Imagine that as the hour of sunset got earlier and earlier, you could simply relocate to a place with a solar schedule you liked better. More time to hang out outdoors hiking. For a bird, a longer day means more light time to gather food and and thus a better place to hatch, raise, and feed hungry youngsters. Not to mention the bonus that more sunlight means more time for tasty plants to grow, which translates to more food to collect and feed to the little ones.

Birds don’t consciously set out on their migrations with a destination in mind. They seem to be pre-programmed with their own unique GPS units. They are guided by land features like coastlines, mountains, and rivers, and also use the sun and stars. In fact, some night-flying songbirds actually memorize certain star patterns in the sky in their first year of life, to prepare them for the flight. Tiny grains of magnetite in or above the nostrils of some migratory birds may also help them use the Earth’s magnetic field, and a few birds can employ their sense of smell on the journey as well.

But how, exactly, birds find their way from here to there remains something of a mystery. And while it would be nice to know precisely how they manage their incredible feat, the elusiveness of answers makes it that much more magical to see and hear hundreds of birds take flight at the same moment, heading for the same place, doing what they’ve been doing for thousands of years.

Visitor Photos