Most nudibranchs take something from their prey to use as their own chemical defense. For example, the chromodorid nudibranchs selectively feed on sponges and steal toxic chemicals from the sponge originally intended to keep animals from living and growing on the sponge. The slugs redistribute those chemicals throughout their tissues to use for defense.

Species that eat sea anemones and other cnidarians can capture the stinging cells from their prey and store them in their tissues. The aeolid nudibranchs store these stinging cells in cerata, which are long finger-like projections that line the body.

A group of slugs that are closely related to nudibranchs, called sacoglossans, steal chloroplasts from algae prey. Instead of stealing for defense, these slugs steal for energy. They redistribute the chloroplasts throughout their tissues and can actually keep the chloroplasts photosynthesizing. These animals are essentially crawling plants.

Dr. Johnson has been named one of the 16 Rubenstein Fellows by the Encyclopedia of Life (EOL). “I am honored and excited to be a Rubenstein Fellow,” says Johnson. “With this award, I will use the Encyclopedia of Life as a platform with which to consolidate and organize historical data, new research findings, and information on chromodorid nudibranchs that is only found in the scientific literature, libraries, natural history museums, and scattered across the web. As a fellow, I look forward to sharing the beauty of these animals with a larger audience and to making scientific information about them more widely available.”

In addition to working as postdoctoral researcher at the Academy, Johnson also works with the Gulf of the Farallones National Marine Sanctuary to train tide pool naturalists at Duxbury Reef—a marine protected area in Marin County—and contributes to the Academy’s exhibits and education programs, including a recent display on the Farallon Islands.

37.7699 -122.467174

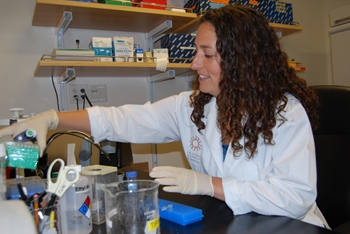

Dr. Rebecca Johnson is a systematic biologist and studies the evolution of color in sea slugs at the California Academy of Sciences.

Dr. Rebecca Johnson is a systematic biologist and studies the evolution of color in sea slugs at the California Academy of Sciences. Chromodorid nudibranch (Risbecia tyroni) Photo credit: Stephen Childs

Chromodorid nudibranch (Risbecia tyroni) Photo credit: Stephen Childs