This outing visits two great landmarks of the northeastern Bay Area—one highly visible, the other well hidden. Both feature the same body of rock: the mighty Great Valley Sequence.

Most of Northern California's bedrock is part of just three large bodies: the granite of the Sierra, the metamorphic rocks of the Coast Range, and the sedimentary rocks of the Central Valley. All three are parts of one entity: a former subduction zone. Picture the Pacific seafloor plate being carried eastward against the North American continental plate and plunging underneath it—subduction. (That's the exact situation today in the Pacific Northwest, and along the whole west coast of South America.) The descending oceanic plate releases fluids into the continental plate above it, which generate magma and big chains of volcanoes. At the same time, the continent scrapes off pieces of the plunging oceanic plate like the bottom of an escalator gathers trash. The volcanoes quickly erode into sediment, which washes offshore in thick beds of sand, boulders and silt. The Sierra is the exposed roots of the volcano belt, the Franciscan Complex is the scraped-off stuff, and the Great Valley Sequence is the offshore sediment.

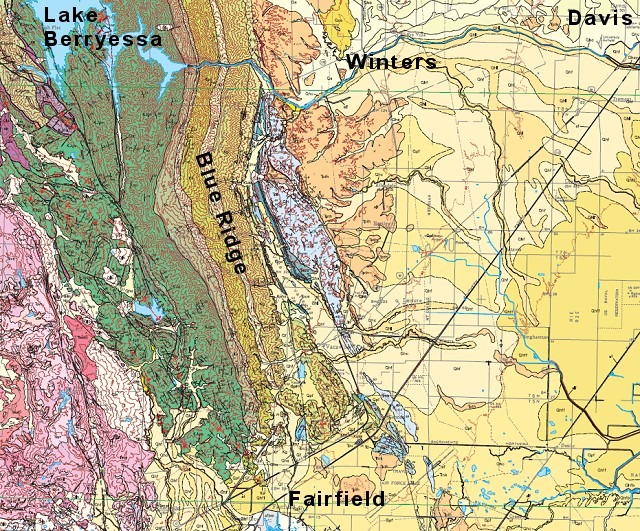

That all happened long ago, and since then the San Andreas fault has slowly ripped apart the neatly organized subduction zone. At the same time, pressure across the fault has pushed up the Coast Range and curled up the edge of the thick blanket of sedimentary rock in the Central Valley. The arrangement is still close to its original simplicity north of the Bay Area, as this map shows.

Below is a closer view of the setting for today's outing. The south end of that long ribbon of Great Valley Sequence rocks is the Vaca Mountains, and the highest part of the range is a sharp hogback called Blue Ridge.

Mount Vaca is its highest point, at the west edge of the leftmost green ribbon to the left of the "i" in "Ridge." If you follow that geologic boundary north, it meets the dam that created Lake Berryessa, Monticello Dam.