The Napa Valley is an intriguing place even if wine doesn't interest you. Its very geography has an intangible personality. Running north-south, the valley is lit differently throughout the course of the day. It has the flat valley floor along the Napa River that you'd expect in a major agricultural region, but odd rocky hills are scattered about the valley with the irregularity of tossed pebbles. On behalf of Napa Valley winegrowers, geologists have studied the underlying soils and rocks, tracing from them a history of tectonic upheaval, recent volcanism and gigantic landslides.

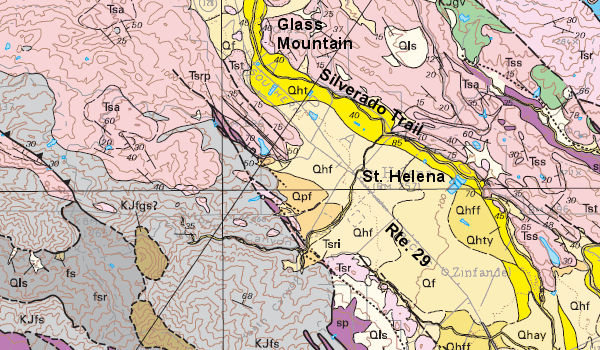

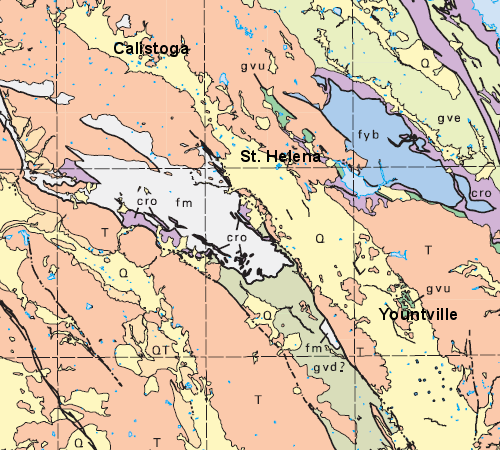

The western side of the valley is the Mayacamas Mountains, here made up largely of marine sedimentary rocks of the Franciscan and Great Valley complexes (100 to 150 million years old). The eastern side is the Vaca Mountains, which consists mostly of much younger lavas of the Sonoma Volcanics (less than 5 m.y.). Here it is in a simplified geologic map.

Each set of rocks responds its own way to California climate and yields its own set of soils, and the floodplain between them mixes the two in different blends. Its wide range of soils and settings is part of what makes the Napa Valley such an endless playground for winegrowers. The same was true in prehistoric times, when the valley was a rich habitat for the Wappo and Patwin tribes and other peoples before them.

And this brings us to Napa Glass Mountain.

The natives made their cutting and scraping tools as needed, chipping them from stone of a few select kinds. The best toolstone is obsidian—a glasslike lava without crystals or bubbles that would mar the sharp edges and flat faces of an effective tool.