With all the construction going on south of Bakersfield on I-5, now is a time to seriously consider a scenic detour of two hours or so that avoids the congestion.

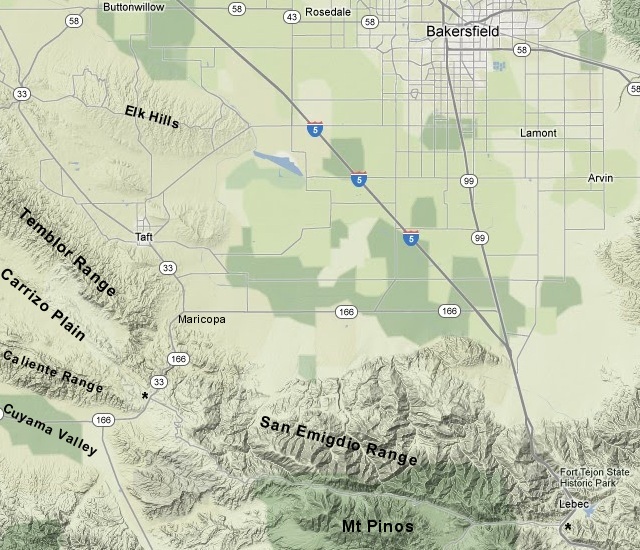

The key points are the little towns of Maricopa and Lebec, and the road between them is named Cerro Noroeste Road at its west end and Frazier Mountain Park Road at its east end. I've marked it with asterisks in this Google Maps clipping. How you get to Maricopa is up to you: state route 33 gets you there from Coalinga, as does state route 58 from Buttonwillow. Another road goes through the Elk Hills if you have extra time.

The geologic overlay (from the interactive state geologic map) shows that this road threads along the part of the San Andreas fault called the Great Bend. Compressive forces across the fault here have pushed up the land into mountain ranges, the San Emigdio range on the north and the Transverse Ranges on the south.

I'll show you the sights from the southbound perspective. The San Emigdios get their name from the patron saint of earthquakes, and this area was badly shaken by the enormous 1857 earthquake that ruptured the ground from Parkfield to El Cajon.