Every kind of natural disaster has its own built-in, unavoidable threat. For storms, it's flooding as the waters rise. For drought, it's ground settling as the water table falls. And for earthquakes of all sizes, it's landslides as the hills come tumbling down.

When the magnitude-6 Parkfield earthquake of September 2004 occurred, witnesses in the tiny Central California town remarked that the hillsides all around erupted in clouds of landslide dust. Seven years later in Virginia, the magnitude-5.8 quake of August 23, 2011, didn't raise a lot of dust in that humid region. But thousands of rock slides occurred, mostly small ones, over a surprisingly large region.

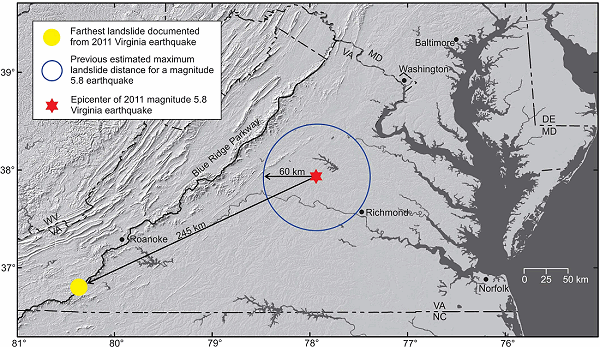

Landslide specialists with the U.S. Geological Survey took it upon themselves to look closely at Virginia, just as they did in Haiti the year before. In the weeks that followed the quake, Randall Jibson drove with Ed Harp in systematic transects away from the epicenter, checking every rocky slope and documenting each example of landslides classified as rockfalls.

They checked the fallen rocks carefully for signs of freshness, like the ripped-up sapling in the photo above, or the presence of still-green grass underneath stones. Where the rocky slopes stopped failing, they drew a line on the map to mark the rockfall limit.

This simple but intensive bit of fieldwork allowed Jibson and Harp to test their model of earthquake landslides with a good set of data. The models were built on data from Western areas with lots of earthquakes, where fresh slides are not always easy to notice, but in Virginia the 2011 quake was the largest in 114 years and left clean evidence everywhere.