Attack of the Killer Electrons! New Mission Searches for Mysterious Space Particles

Attack of the Killer Electrons! New Mission Searches for Mysterious Space Particles

They’re out there... Traveling at close to the speed of light high above the Earth and damaging any satellite in their path. They’re called “killer electrons” and this year, Bay Area researchers are working with a new NASA mission to unlock their mysterious behavior.

Killer electrons aren’t a threat to life on the ground, but they are a concern for the more than 1,000 satellites orbiting the planet. Satellites we depend on for everything from storm warnings to GPS navigation to TV programming.

“Every major sports event -- certainly every Olympic Games, the Super Bowl as well as the Academy Awards,” says Jean-Luc Froeliger, describing events carried by his company, Intelsat, a global satellite operator.

Scrambling Satellite Data

One thing Froeliger knows: space is not a dull place.

“In April of 2010, we had an event on our Galaxy 15 satellite,” says Froeliger. “We were sending commands to the satellite but the satellite was not accepting any command.”

Galaxy 15 had become a $100 million zombie.

“The satellite started to slowly drift,” says Froeliger, potentially interfering with satellites around it. Intelsat worked for months to reboot Galaxy 15, just about all that can be done with a satellite 22,000 miles away. Eventually, it came back online.

Froeliger says it’s all part of operating in the harsh environment outside our planet. “Satellites are constantly bombarded by high energy particles that flow from the sun,” he says.

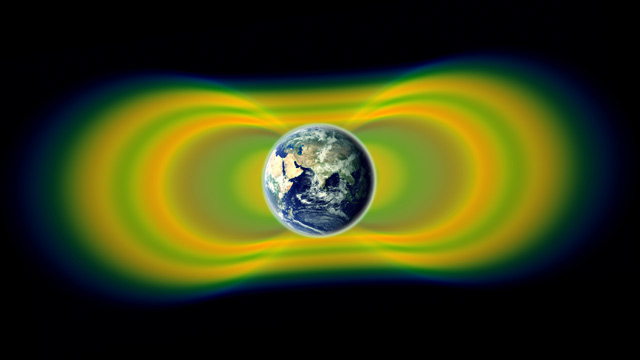

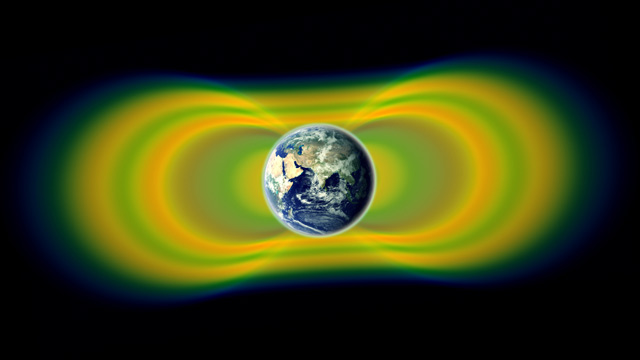

Our sun sends out a stream of charged particles called the solar wind. This year marks a solar maximum, the peak of the sun’s activity, which can have big effects on our planet. “When those particles come close to the Earth, they get trapped by the Earth’s magnetic field,” Froeliger says.

Picture the Earth as a donut hole, and the magnetic field as a giant, invisible donut around it. The charged particles trapped inside the field create radiation belts. Galaxy 15, like other geosynchronous satellites, flew right through the belt and was bombard with charged particles, which created a short circuit.

But even just one particle – a single electron – can cause problems. “Some of them can penetrate metal and they can damage the electronics inside the satellite,” Froeliger says.

At least once a month, a killer electron goes through a satellite’s exterior and hits a computer chip inside. “The data that is stored in the computer gets corrupted,” says Froeliger, causing temporary or permanent damage.

Studying Electrons in New Detail

“Why they call them killer electrons is because they can penetrate several millimeters of aluminum or steel and get to you,” says David Smith, a physicist at the University of California, Santa Cruz.

Smith is standing on the roof of a four-story building on campus, where a small shed is used as their mission operations center.

“What we’re studying is electrons that come slamming down onto the atmosphere from Earth’s radiation belts,” he says. The electrons are stopped there, but Smith says you can still see their fingerprints.

Smith and his colleagues with the BARREL project have launched large research balloons to look for electrons falling out of the magnetic field. The balloons are released from Antarctica and travel 20 miles up, sending data back to UCSC.

Smith says understanding the risk from killer electrons is tricky because their numbers are constantly in flux. “On a given day, you may have a thousand times more of these very high-energy electrons in the belt than you did a few days previously.”

They’re also mysterious because killer electrons don’t start out as killers. Electrons arriving from the sun are low-energy for the most part. “It’s after the Earth captures them that something ramps them up to these really high energies,” Smith says.

To find out what that something is, Smith and his team are collaborating with a new NASA mission. In August, NASA launched the Van Allen Probes, two satellites designed to take detailed measurements inside the radiation belts.

In December, the probes made a recording of a mysterious phenomenon in the radiation belts: electromagnetic waves. “We’ve known about these waves for quite a long time but we’ve never had the kind of measurements that we needed to really understand them,” says Craig Kletzing of the Van Allen Probes mission.

Scientists theorize that the waves could be responsible for accelerating killer electrons. “The waves give energy to particles much like a surfer,” Kletzing says. Think of the waves as the ocean and the electrons as little surfers.

These results and others from the mission are expected to give scientists a better understanding of the Earth’s radiation belts. That could lead to better forecasts about when they’re particularly dangerous – something that’s key for NASA and for the satellites we depend on.