Water Recycling Comes Of Age In Silicon Valley

This fall, Santa Clara county residents will get a new source of water. This water is local and pristine. In fact, it's cleaner than almost anything coming out of taps today. But – for now at least – no one will drink it.

Instead, water from the $68 million Silicon Valley Advanced Water Purification Center will flow into segregated, purple pipes to irrigate lawns and cool power plants.

That's because the water is recycled from wastewater – sewage – from a wastewater treatment plant across the street. Engineers say it's possible to purify sewage water until it's cleaner than much of what residents drink today. The bigger challenge, they say, is convincing people to drink it.

The need for this new Bay Area plant is well established, says Dick Luthy, a professor of environmental engineering at Stanford University.

“We're basically at the limits of our current water supply,” he says.

California's population will increase in coming years. Climate change will make snowmelt from the Sierra Mountains more erratic. Policy battles over farms and endangered fish in the Delta mean more competition for less supply. The important thing to realize, says Luthy, is that where we get our water and what we do with it have to change.

“What we're realizing now,” he says, “is that the ways of the past are not the ways of the future.”

When it comes online, the plant will produce eight million gallons of purified water a day, using some of the most high-tech water purification systems available today.

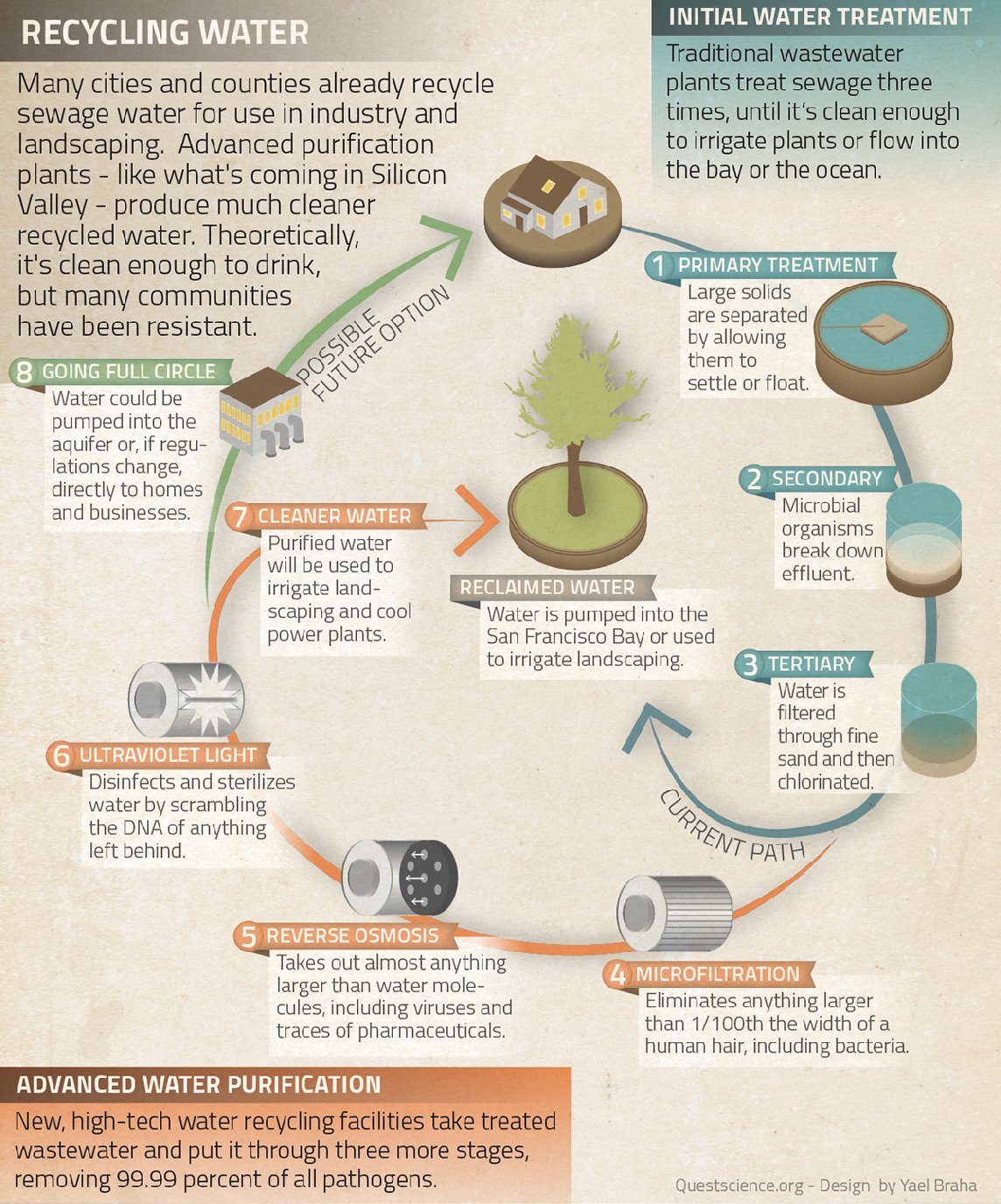

The first step is microfiltration. Canisters filled with spaghetti-like fibers filter out anything larger than one micron – 1/300th of the width of a human hair – including bacteria. Next, high-pressure pumps force water through a reverse osmosis membrane, with pores so small they exclude anything larger than a water molecule, including viruses and traces of pharmaceuticals.

Finally, the water gets zapped by ultraviolet rays to scramble the DNA of (and therefore sterilize) anything that might be left living in it. “We are removing 99.99 percent of all pathogens,” says Crystal Yezman, an engineer for the Santa Clara Valley Water District.

San Jose's been recycling water for more than a decade, but this water will be much cleaner. Theoretically, says plant spokesman Marty Grimes, you could drink it.

Unlike water from the embattled Delta, or Hetch Hetchy system, the supply – sewage – is basically boundless. And, as Grimes points out, local.

“This water is ours,” he says. “No one can take it away”

Initially, at least, this water will be more expensive than current water sources, like the Delta or underground aquifers. It will also be more expensive than measures to conserve current water supply, like low-flow shower heads or more efficient toilets.

But managers expect recycled water costs to fall in the future, as the practice becomes more common, and say that recycled water is much less expensive than other “new” sources of water, such as desalination.

Still, water recycling has been a tough sell here in California. San Diego’s recycling plan nearly died in 2007 when the mayor uttered the three most dreaded words for this industry: “Toilet to tap.”

A few years ago Brent Haddad, an environmental engineer at UC Santa Cruz, noticed that he kept finding himself at industry meetings listening to water managers complaining about an “irrational” public unwilling to accept perfectly clean, recycled water.

(For more on this, here's a terrific NPR story from a couple years ago.)

So Haddad conducted a national survey, to try and understand this resistance and what it would take to change it.

“We found it has nothing to do with level of education or any other personal demographic traits, like race, religion or salary,” says Haddad.

Fear about drinking recycled water, he says, is “a great equalizer.”

So how do you convince the public to embrace recycled water? Haddad says the first step is to explain to people how the water is treated, and why it is safe to drink.

Part of that process is explaining that Americans have effectively been drinking recycled water for generations.

Take, for instance, cities along the Mississippi or Colorado Rivers. Cities treat their sewage and pump it back into the river. Downstream, other cities suck water from the river, treat it, and pipe it to customers.

“Any city that gets its water from Colorado river, like Las Vegas and southern California utilities,” says Dave Smith, Managing Director for Water Reuse California. “are getting some of their water supply through incidental potable reuse.”

Brent Haddad says another way to reassure customers is to use what he calls “psychological cleansing.”

“You have to break the memory, the line of history of the water.”

In other words, re-write the history of the water, editing out the part about sewage. One way to do this is to take recycled water and put it back into nature, for instance, a river.

“That river is something that's comforting to people. We don’t have to think that the water came through a city. We just begin the history of the water in the river itself.”

In fact California's Department of Public Health, which works with utilities to design water recycling facilities, currently requires this kind of “environmental buffer.” (Though the Department is currently reevaluating that policy.)

An environmental buffer is built into the design of the world's largest water recycling facility, operated by the Orange County Water District.

Instead of a river, the county's Groundwater Replenishment System cleans treated sewage, then pumps it into underground aquifers, where it mixes with other water and eventually gets pumped up, re-treated, and piped to peoples’ houses.

Water managers call these systems “indirect potable reuse.”

“We put it back into the ground and then eventually it becomes part of the water supply,” says the district's general manager Michael Markus.

Markus says getting water clean enough that it can be put back into an aquifer is the easy part. Much more of a challenge, he says, was convincing the public that the water would be safe enough to drink. The district decided on a policy of total transparency, he says, and started planning a series of public meetings.

“We went to our local state elected officials, the health and medical community, environmental groups, Rotary clubs,” he says. “We talked to the Sons and Daughters of the American Revolution, scouting troops... anyone who would want to hear or receive a presentation.”

This whole process took nine years. Tours of the facility are still available.

The irony is that when you put recycled water back into the ecosystem, it actually gets dirtier, and has to be treated again.

Markus says it's “frustrating” to watch this facility pump pristine water into a hole in the ground. But he realizes that winning people over to recycled water is an ongoing process.

That process is farther along in Southern California. In Los Angeles, says Dave Smith, “One-fifth of the population is already getting part of their water supply from indirect potable reuse.”

In West Texas, which faces critical water shortages, at least two recycling facilities skip the “environmental buffer” stage entirely, using advanced purification to treat wastewater and pump it directly to customers.

Here in Northern California, the process of use and acceptance is just beginning. When the Silicon Valley Advanced Water Purification Center opens up in late fall, the pristine water will be destined for golf courses and power plants.

But one day, if policies and public opinion change, it could be there for drinking, too.