Something is happening in the Appalachian forest, something deadly. The mighty stands of hemlock, the old-growth guardians of these ancient mountains, are succumbing to death by a billion cuts.

Go out into the Alleghenies, the Blue Ridge, or the Smokies and seek out the rushing waters of a mountain stream. Chances are you’ll see what I’ve seen: a skeletal scene with hundreds of giant hemlock trees standing dead on the riverbank, their leafless limbs reaching up to the sky like penitents begging for absolution. Both eastern (Tsuga canadensis) and Carolina (T. caroliniana) hemlocks are falling victim to an exotic insect called the hemlock woolly adelgid (Adelges tsugae), and the riverside areas of the mountainous eastern United States will likely never be the same again.

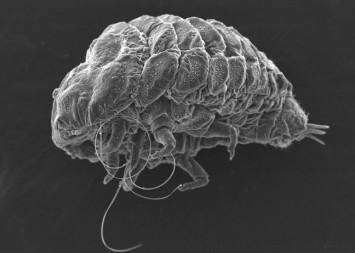

Accidently introduced to Virginia in the 1950s through the importation of ornamental Japanese weeping hemlocks, the hemlock woolly adelgid (HWA) is a purplish insect less than a millimeter long. It’s detectable mainly by its egg casings -- ghostly pale fibrous masses clotting the underside of the hemlock’s shoots. Over several years the HWA larvae feed on the phloem sap that carries life-giving sucrose to the tree’s elegant flattened-needle leaves, eventually causing them to wither and fall from lack of nutrients. And as the leaves fall, the trees starve.

Hemlocks are a keystone species, critical to the mountain waters of the eastern U.S. They are also our primary old-growth trees, living for more than 800 years and anchoring a complex riverine ecological community. Their great shaggy forms, 175-feet tall and more, line our highland waterways and provide year-round shade and soil stabilization to keep streams running cool and clear. Removing hemlocks has increased siltation and exposed the rivers and forest floor to greatly increased sunlight. This results in warmer waters and enormous changes in the vegetative composition of the forest floor, with attendant degradation of wildlife habitat.

HWA has spread throughout much of the hemlocks’ range and killed countless trees, a massive loss to biodiversity and the integrity of our mountain headwaters. The Alliance for Saving Threatened Forests, a coalition composed of multiple universities and agencies based at North Carolina State, has arrived at two potential (and unfortunately long-term) methods of combatting HWA.

The first involves the remarkable discovery that a tiny fraction of hemlocks appear, for unknown reasons, to be largely resistant to HWA infestation; that is, the bugs permeate them like any other, but these trees are somehow able to carry on regardless (foresters refer to a grove of veteran survivors in New Jersey as the “Bulletproof Stand”). Perhaps over time the secret of their hidden strength can be understood and shared with the few isolated hemlocks that have as yet managed to avoid infestation.