Every year about 85 million gallons of a toxic waste that is known to promote cancer is carefully painted across about 170 square miles of American cities and suburbs, a swath as big as the city of New Orleans.

As incredible as that may sound, that’s the conclusion squarely presented by a growing body of research that looks at a gooey black pitch made from a substance known as coal tar. It’s a kind of creosote, the stuff used to weatherproof telephone poles and railroad ties.

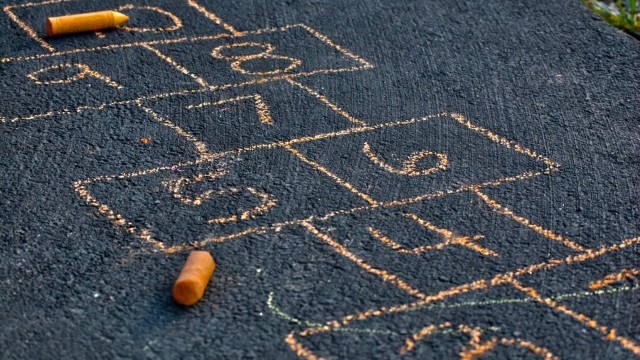

It’s also one of the two main ways Americans use to “seal” asphalt parking lots and driveways. It makes the asphalt look blacker and is intended to keep the pavement from wearing away so fast. Researchers are most interested in a class of chemicals contained in asphalt sealers known as “polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons,” or PAHs. And coal tar-based sealers are dangerous enough in the opinion of some local and state governments that they have been banned. In 2011 Washington became the first state to forbid the use of this kind of sealant, followed by Minnesota last year.

If you’ve ever walked by a parking lot or driveway that’s recently been sealed with coal tar, your nose most likely told you so. The “aromatic” part of PAHs means that you can smell the chemicals emanating from the recently sealed pavement , especially when it bakes in the sun. Recent research shows that large and potentially dangerous amounts of these harmful chemicals are released into the air in the days, weeks, and even months after the pavement is sealed – more, in fact, than what is put out by all the cars in the country.

Scientists also looked at what happens to the toxic coal tar sealants after they have sat on the asphalt for a few months or years and start to peel off in tiny bits. Car tires, rain, foot traffic, snowplows, and the freeze/thaw cycle all cause tiny bits of the sealant to “abrade,” as scientists say. Little bits of the black stuff flake off.