If scientists are allowed to perform a simple genetic engineering procedure, they will be able to offer a reprieve to a small group of women who are condemned to pass certain fatal genetic diseases to each and every one of their children. This relatively straightforward procedure will allow a woman with one of these diseases to have a healthy baby with whom she will pretty much share half of her DNA. Only the tiniest snippet of DNA would come from an egg donor.

This procedure isn’t for all women in this situation though; it can only help women who carry certain mitochondrial diseases. People with these genetic diseases suffer because they have mitochondria that don’t work properly. Since the mitochondria are the organelles in the cell responsible for making the energy that keeps each of us running, defective mitochondria can have pretty severe effects. In some cases, it causes death at a very early age.

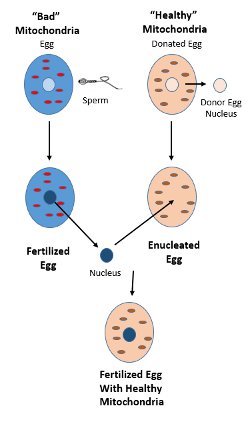

As you can see in the image on the right, the procedure to deal with this swaps out the defective mitochondria in a woman’s egg for the functioning mitochondria of a donated egg. It really is just taking a perfectly healthy nucleus from the fertilized egg and putting it into an egg with perfectly healthy mitochondria. The newly combined fertilized egg is then put back into mom where it can go on to develop into a mitochondrial disease-free baby.

Unfortunately, not every woman carrying a mitochondrial disease can be helped with this procedure. Only those who carry a mitochondrial disease caused by mutation(s) in her mitochondrial DNA (mtDNA) can benefit.

Mitochondria are unique in animal cells because they have a tiny bit of their own DNA (probably an evolutionary leftover from when they were free living beasts hundreds of millions of years ago). This mtDNA only makes up about 1/300,000th of our total DNA and has only about 37 genes, but it can still cause problems when it is damaged. And it is this DNA that also makes this procedure so controversial.