Desalination's Future in California Is Clouded by Cost and Controversy

Desalination's Future in California Is Clouded by Cost and Controversy

Once thought to be the wave of the future, desalination is proving to be a tough sell in California.

The idea of turning ocean water into drinking water has long held promise, but the dream of sticking a straw in the sea and getting unlimited clean water simply by opening the spigot of technology — that’s looking less and less likely here.

Scarcely a decade ago, when “desal” was relatively new to the state and optimism was high, there were 22 different proposals for plants up and down the California coast. Since then, Marin, Santa Cruz and other coastal cities have scrapped their plans. A tiny desal plant has been constructed in Sand City, north of Monterey, but only one significant project has been completed.

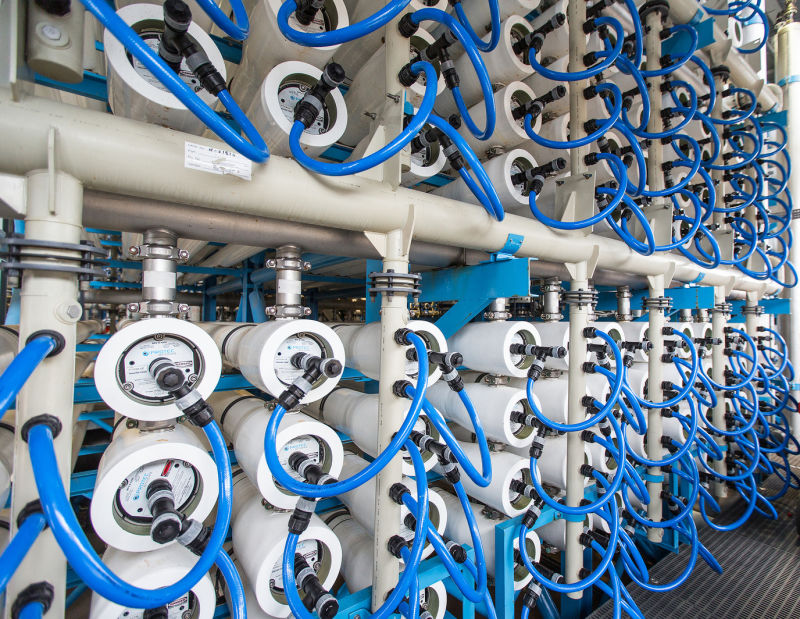

It’s in Carlsbad, 30 miles north of San Diego, and it’s the largest desal plant in the nation, built and operated by Boston-based Poseidon Water. Peter MacLaggan looks up at the giant building like it’s a monument to common sense.

“If you don’t plan for the future and ensure you have an adequate supply,” says MacLaggan, a senior vice president with Poseidon, “you’re going to find yourself in a crisis that costs a lot more than if you plan ahead and do it right.”[edge_animation id=”19″ left=”auto”]

He says one of the reasons the San Diego area managed to get a desal plant built is because of its location at the tail end of the state’s water pipe.

“When you look at San Diego and where it’s located in the water supply system in California, it’s at the end of a very long plumbing system, 500 miles from its nearest source,” MacLaggan says.

That intensified the need for another water supply, he says. This plant supplies about 10% of the San Diego area’s water needs.

Environmental Costs

MacLaggan and other proponents hold up Carlsbad as proof-positive that desal works. But just 60 miles up the coast from Carlsbad, you get a different view; another one of these gigantic plants is proposed for a white expanse of sand at Huntington Beach.

Ray Hiemstra says this spot is the poster child for why desal doesn’t work.

“It’s going to kill marine life, pollute your water, increase your rates and most importantly we don’t need it,” he says.

Hiemstra works for Orange County Coastkeeper, a South Coast environmental watchdog. He starts to run out of fingers as he enumerates all the other reasons to reject the plant proposed for Huntington Beach. There’s an active earthquake fault here. It’s in a tsunami zone. And its elevation is so low that rising seas might inundate the proposed site.

One of the big problems with taking the salt out of seawater, says Hiemstra, is what to do with it after it’s removed; that highly concentrated brine typically goes back into the ocean. At Huntington Beach, you can see the outflow pipe just a thousand feet offshore.

“It’s right there,” he says, squinting and pointing at the surf line. “There’s a couple of surfers out there, right by it.”

When you increase the level of salt in the water, he says, even diluted to low levels, it disrupts marine life all around that spot.

“Anything that comes through here and realizes that brine plume and higher salinity, even a little bit higher salinity, it’s just going to move away.”

That area of less sea life and the water at the outfall can drift south, he says, affecting the food supply of the California least tern, a threatened bird living nearby.

And there’s another problem with putting water from a desal plant back in the ocean: it may have residue from the chemicals used to treat the water, such as chlorine.

The Carlsbad plant isn’t even a year old but state officials have cited it a dozen times for environmental violations. That includes what they call “chronic toxicity,” from an unknown chemical used in water treatment that has been piped into the ocean. The company is still trying to identify, isolate and clean it up.

Expensive Water

Despite their severity, environmental concerns aren’t the main barrier.

“In general, one of the big challenges has really been the cost,” says Heather Cooley, an analyst with the Pacific Institute in Oakland. The nonpartisan research group recently issued a lengthy report on the state of desalination in California.

Beyond the environmental cost is the actual price tag: the plant in Carlsbad cost $1 billion to build, with a rough estimate of $50 million a year for the power to run it. The estimated cost of the water to San Diego is about $2,300 dollars an acre-foot — more than double the cost most Southern California cities pay for water. (An acre-foot is enough water to supply one-to-two California households per year.) And ratepayers need to pony up for that water even during rainy seasons when the price of water from more traditional sources plummets.

Cooley says the expense is the main reason communities have turned away from desalination.

“As many of these projects sort of went through the process and started looking more seriously at the cost,” she says, “there started to be concern that that was too high, that there very likely were other options.”

Those options include treating wastewater and putting it back into the water table, catching stormwater runoff, or simple conservation efforts. That’s the future most agencies are pursuing in California.

Cooley says desal used to be high on the list of possible water sources, but now it’s closer to the last choice on the list.

“There are some people who still hold onto it as the Holy Grail,” she says, “that thing you’re seeking that’s going to solve our problem.”

Now, six years into the drought and counting, the demand for water sources is only liable to intensify. That could set the stage next year for yet another fight over approval for the Huntington Beach desal plant.