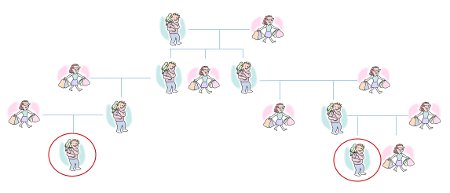

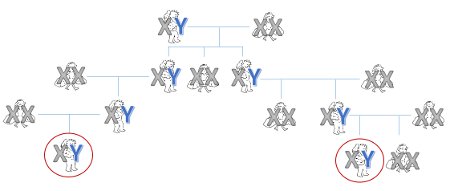

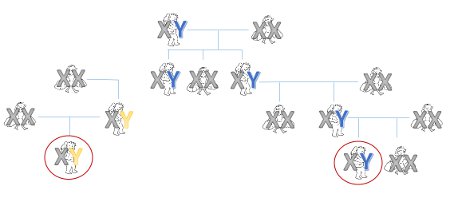

It is a fact of life that some men are unknowingly raising kids that are not biologically related to them. One common way for this to happen is if their partner has an affair and gets pregnant. This predicament is common (or worrisome) enough that there are even magazine articles that come up with mostly wrong ways to tell if a child is really yours.

Until recently, though, no one had a really good idea about how many men were in this situation. The 3-5 percent number commonly bandied about was extrapolated from a pool of men that had done some DNA paternity testing. This obviously skewed sample meant that these numbers were probably too high.

Now that DNA testing is becoming cheaper and easier, we can get better numbers. A couple of recent studies from Western Europe suggest that somewhere between 0.6 and 0.9 percent of men are unknowingly raising another man’s child. While this is still a lot of men, it is much less of a problem than many people thought. And according to another new study, it turns out that the problem wasn’t much worse a few hundred years ago (at least in one region of Western Europe). This last result was definitely unexpected.

Most people who thought about this issue had assumed that the problem must have been worse in the past. They assumed that the rate of women having an affair held steady at around 15-50% but since these women did not have access to either modern birth control or safe abortions, they must have had more kids that weren’t related to their husbands. Turns out this may not have been the case.

Researchers found that the numbers of men unknowingly raising another man’s child held constant at around 1-2 percent per generation over the last four hundred years in Flanders in Western Europe. This is in contrast to previous estimates that had put the numbers as high as 8-30 percent.