If You Think You Understand the Death of the Dinosaurs, You’re Wrong

If You Think You Understand the Death of the Dinosaurs, You’re Wrong

A “Jurassic Park” sequel is once again dominating the box office this summer, underscoring the star power of dinosaurs. But, captivated as we are with bringing them back, scientists still argue over what caused their extinction 66 million years ago.

It’s not as settled as you might think.

I put the question to Charles Marshall, director of the University of California Museum of Paleontology in Berkeley: “Do we know what killed the dinosaurs?”

“No.” He repeated it emphatically, “No.” (Pause) “I guess the answer is no.”

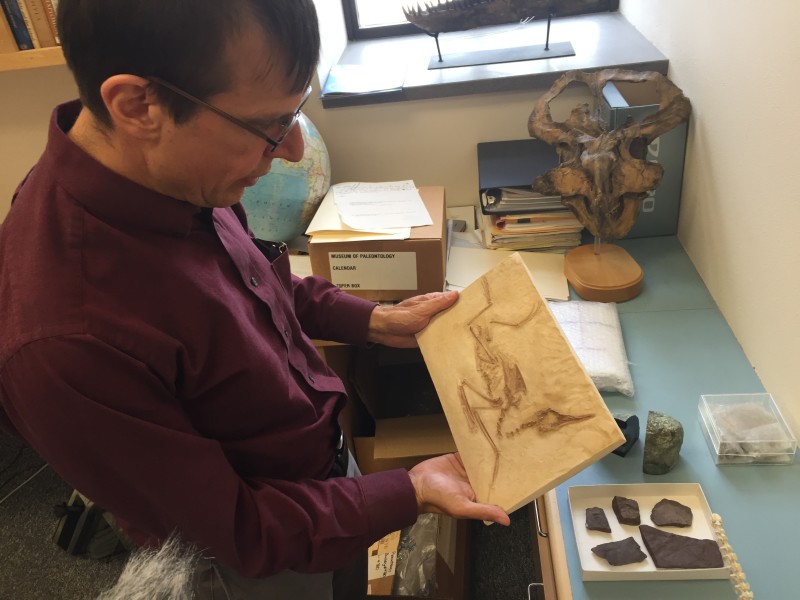

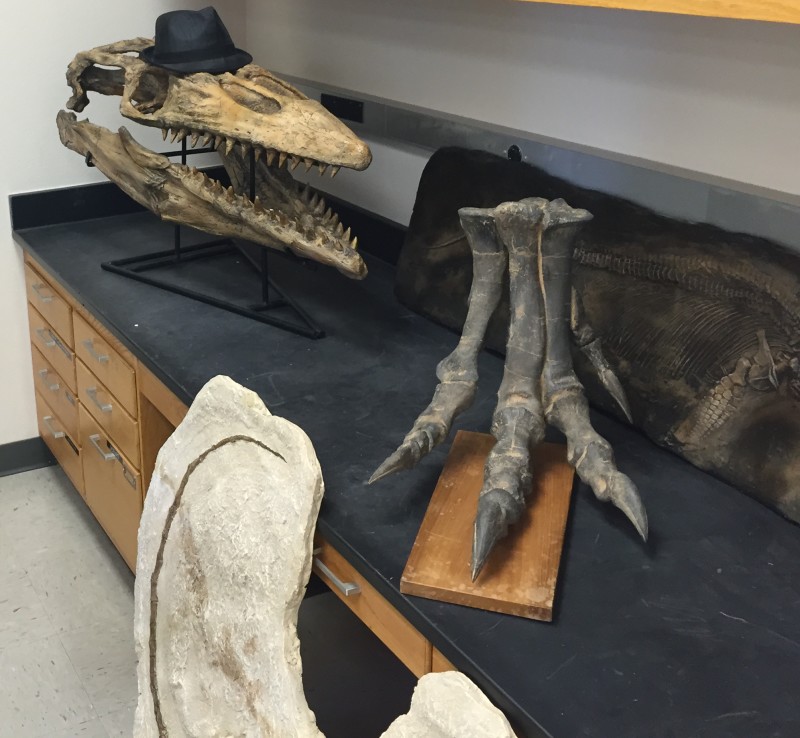

We were sitting in Marshall’s fifth-floor office, not far from the skull of a triceratops relative and some fossilized feet the size of tree stumps. He told me as recently as the 1970s, there wasn’t even a good guess as to what killed the dinosaurs.

“There were dozens of hypotheses, and basically no one took any of them seriously.”

That is, until Berkeley scientists — led by Luis Alvarez (a Nobel laureate in physics) and his geologist son Walter Alvarez — brought forward the idea that Earth was slammed by a meteorite or comet roughly the size of San Francisco.

The theory and its backers got a major boost a few years later with the discovery of a 110-mile-wide crater on present-day Mexico’s Yucatan Peninsula.

“With the finding of the smoking gun, then the fact that there was a large meteorite started to become broadly accepted,” Marshall said. “So it sort’ve started to evolve into meteorite versus volcanism as the two hypotheses.”

Indeed, volcanoes have been hard to keep off the list of known suspects. Going back hundreds of millions of years, every other big extinction (barring the present day’s) is connected to volcanism.

Plus, around the same time as the meteorite impact and the disappearance of dinosaurs from the fossil record (along with many species, down to tiny ocean creatures), there was also a massive wave of volcanic activity in India – in a place known as the Deccan Traps.

So for years scientists have argued back and forth: Impact! Volcanoes! Impact! …

Until recently, when Berkeley geophysicist Mark Richards offered this idea: “I realized that the size of the impact is likely large enough to have triggered volcanic systems around the planet.”

Bigger Than Big

Richards calculates that the energy of a rock the size of Mount Everest slamming down from space was enough to unleash a magnitude 11 quake. That is not a typo. When I told Richards I thought the scale only went to 10, he told me that’s actually not true.

In earthquake terms, higher than 10 is a nightmare. Such a quake would be hundreds of times worse than the “big one” that hit San Francisco in 1906. Richards says it would’ve rattled the globe – even the volcanoes on the other side of the world in India.

“So the idea is that system may have been kicked into high gear by the impact.”

Richards is careful to say that if he’s right, and the two events are connected, we still don’t know precisely what killed the dinosaurs. Rather, the proposal points the way toward a new investigation, says Paul Renne, director of the Berkeley Geochronology Center and coauthor of Richards’ paper.

“We just have to abandon the idea that it’s one or the other,” Renne said.

Both the impact itself and a wave of volcanism would have the potential to unleash massive outpourings of noxious gases, resulting in wild swings in temperature.

One factor might’ve been a release of CO2, say from so much vaporized limestone, resulting, along with other greenhouse gases, in a long-term warming effect.

Renne says there could’ve also been an abundance of sulfate aerosols, “which, if they get up into the atmosphere, can actually reflect enough sunlight it results in cooling.”

In fact, one could argue for a double event – sudden cooling first, followed by a long, hot period from the greenhouse effect. Whether the dinosaurs died in a single bad weekend, or the lifetime of an animal as the food web collapsed, or several millenia, remains unclear.

“The potential effects of either an impact or massive volcanism in many respects can be the same. The symptoms would be indistinguishable,” Renne says.

Increasing Precision

To better understand the impact and its possible connection to the eruptions in India, the next step will be establishing a narrower range of dates. For Renne, this entails using a basement room full of mass spectrometers to test rocks from the Deccan Traps. Canvas sacks full of such rocks are heaped in the hallway outside his office.

“I’m a rock aficionado, and I have lots of beautiful rocks and big crystals. These are some of the ugliest rocks you’ll ever see,” Renne said, producing a sample that to my untrained eye might as well have been gravel from a nearby quarry.

Dating these rocks is a slow process, involving shipping a few dozen milligrams out of state to be irradiated and then sent back for testing. It can take months.

Nearby is a wood-paneled room that houses a magnetometer — another tool for dating prehistoric rocks. This is Courtney Sprain’s speciality; she’s a Ph.D. student who also coauthored Richards’ paper.

Sprain spends part of each summer in Montana gathering samples from coal beds, and told me by the end of each day she tends to resemble a chimneysweep.

When the Earth’s magnetic core shifts (we’re not sure why this happens), it leaves a record in the rocks. Sprain teases out these clues to refine the timescale.

“We’re getting precision of 20-thousand years,” she says, “whereas before it was 500-thousand, a million.”

Really, what would be ideal, if unrealistic, is precision down to what day of the week the impact occurred. But getting it under 10,000 years would be helpful.

Geologist Eldridge Moores, a distinguished professor emeritus at U.C. Davis, known for his role in the John McPhee book “Assembling California,” says it’s like a detective trying to figure out someone’s exact time of death.

“You have to know that – it’s essential information before you can answer the next question, which is why. The same is true with the dinosaurs.”

Moores was sitting with me at his house in Davis, a copy of Mark Richards’ paper on the dining room table before him, when I asked him the question: Do we know what killed the dinosaurs?

He told me no — but he thinks we’re getting closer.