Of course spacecraft and astronauts and robot rovers are sexy. So are scientific submarines and their dives to the deep seafloor. But today I want to speak up for research aircraft and the plucky geniuses who maintain and fly them. They penetrate hurricanes; they peek high above thunderstorm complexes at night for a glimpse of sprites; they fly over the El Niños and the poles.

Most of all, aircraft are an indispensable part of our effort to understand Earth’s climate and the atmosphere that sustains it. They’re worthy of graphic-novel treatment, if there’s an artist out there who’s up for it. Here’s the story line: Next week three of the world’s best scientific aircraft will team up on a six-week mission, called CONTRAST, to explore a key part of the world’s climate system.

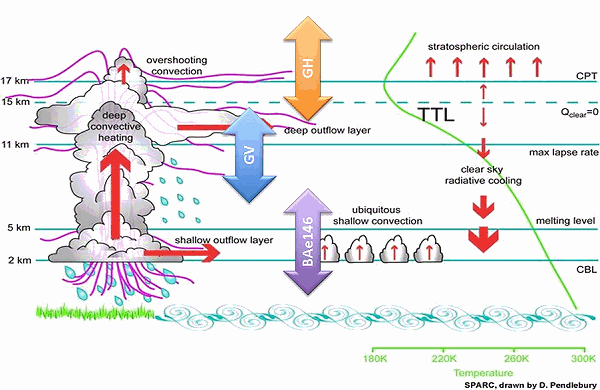

The tropical western Pacific, south of Guam, is the opposite of Antarctica: the warmest part of the ocean. As we shiver through winter, the atmosphere above the Western Pacific Warm Pool is at its most active. The region acts like an immense chimney, with thunderstorms and other deep convective disturbances pushing huge quantities of air some 20 kilometers straight up from the sea surface. Some of this air bursts into the quiet stratosphere, where it stays for years and spreads outward across the entire world. The West Pacific chimney is where most of the stratosphere’s input of surface air happens. Models of global climate need to account for the influence of this great engine of air, but its makeup is poorly known.

One notable ingredient of oceanic air is a set of organic bromine compounds emitted by sea life. Although these gases usually are swiftly neutralized by ozone within 100 meters of the sea surface, the western Pacific chimney is active enough to funnel bromine into the upper atmosphere, where it erodes the stratospheric ozone layer that protects us from damaging ultraviolet radiation. Volcanoes also inject bromine into the stratosphere, but in the Pacific chimney we can study the same process all the way up from the sea surface without dealing with a volcano’s dangers.

Three state-of-the-art aircraft will team up for CONTRAST (CONvective TRansport of Active Species in the Tropics). Two have human crews while the third, the high-altitude star, is a robot. Between them, they can cover the whole altitude range of this energetic region from the wavetops well into the stratosphere.