Archerfish Says..."I Spit in Your Face!"

Most people would find getting regularly spit in the face an unacceptable occupational hazard.

But that’s life for researchers like Morgan Burnett, a biologist at Wake Forest University in North Carolina who studies archerfish.

“If they see something moving up there, they’re gonna spit at it,” he said.

That includes your eyes, which draw the fish’s attention because of their shine, contrast and darting movement.

Burnett’s been hit too many times to count. “I’ve taken a few surprise shots,” he said, “this cold stream of water just hits you.”

“Spitting is exploratory,” explained Caitlin Newport, a zoologist at the University of Oxford, who also studies the fish. Her subjects fire at most things that move within their field of vision, she said, “especially things that are shiny and move quickly.”

Archerfish normally do their spitting in the mangrove forests of Southeast Asia and Australia, where they take aim at ants, beetles and other insects living on the trees’ half-submerged roots. The fish’s high-pressure projectiles knock prey from their perches into the water, and the fish swoops in.

The day I went to scout this episode of “Deep Look” at the California Academy of Sciences in San Francisco, I arrived when feeding time was getting underway. As the archerfish scanned the artificial vines of their aquarium for crickets, they reminded me of dogs intent on chasing a stick. The way they track their targets, take aim, and strike is focused, almost cold-blooded.

This novel feeding behavior, restricted to only seven species of fish, has attracted the attention of researchers ever since it was first described in 1764.

John Albert Schlosser, an eminent Dutch naturalist, described the scene this way to the Royal Society of London almost 250 years ago:

“With surprizing dexterity, it ejects out of its tubular-mouth a single drop of water, which never fails striking the fly into the sea….”

It’s pretty charming to watch, as you can tell from my reaction.

Since Schlosser’s time, researchers like Burnett have refined our understanding of the fish’s technique. For one, that single drop isn’t a drop at all, but a jet.

The jet’s tip and tail unite at the moment of impact, which is critical to the success of the attack, especially as the target distance approaches the limit of the fish’s maximum spitting range of about 6 feet.

“When the fish fires the shot,” Burnett explained, citing the work of other researchers in Germany who first used high-speed cameras to observe the projectiles in 2014, “the water leaves the mouth as essentially a very long stream. But during flight, the stream merges into a ball.”

It takes a certain amount of force to knock an insect off its perch. When the tail of the stream adds its size to the stream’s head, it bumps up the overall force of the strike, even as the projectile slows in the air.

At that moment, thanks to Newton’s second law of motion, whammo! —dinner is served.

The fish accomplishes this feat of timing through deliberate control of its highly-evolved mouthparts, in particular its lips, which act like an adjustable hose that can expand and contract while releasing the water.

So in a way, to hit a target that’s further away, the fish doesn’t spit harder. It spits smarter.

Humans have always assumed we’ve cornered the market on intelligence. But because of archerfish and other bright lights in the animal kingdom—not all of them mammals—that idea is itself evolving.

The German scientists, including Stefan Schuster at the University of Bayreuth, even suggested that the archerfish’s hunting practice constitutes tool use. In the 2014 paper, he wrote that the fish can “change the hydrodynamic properties of a free jet of water—a task considered difficult in human technology.”

According to evolutionary theory, Schuster reminds us in his paper, the invention of throwing (stones, spears) by humans called extra neurons into action, enlarging the brain over time.

So if archerfish are basically throwing water, are they on some kind of evolutionary fast track, about to make some giant leap with a new brand of water-based technology, like the aliens in James Cameron’s The Abyss?

Just how smart is an archerfish?

Last June, another experiment, conducted at the University of Queensland, prompted headlines like “‘Smart’ Fish Can Recognize Humans.”

The headline’s a stunner because, according to Newport, who’s since moved to Oxford, “Recognizing faces has been considered something uniquely human. We think only we can do it.”

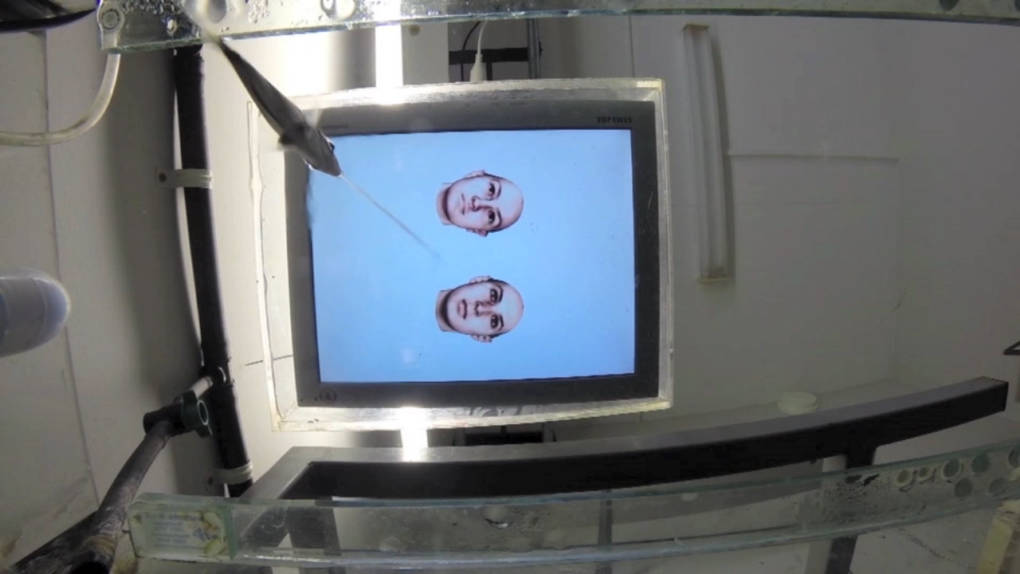

Using the archerfish’s spitting habits as a starting point, Newport trained some lab fish to spit at an image of one human face with food rewards. Then, on a monitor suspended over the fish tank, she showed them a series of other faces, in pairs, adding in the familiar one.

I asked Newport why she used faces instead of, say, apples and oranges. Facial recognition in humans takes place in the neocortex, she told me, and fish have no neocortex. Instead their eyes are wired to an optic tectum, a more instinctual, primitive part of the brain. Recognizing a face should be beyond them, anatomically speaking.

She wanted to see how they’d do.

When the trained fish saw that familiar face, they would spit, to a high degree of accuracy. In a sense, the fish “recognized” the face.

In a sense. According to Newport, however, what her experiment showed is only that an archerfish could discriminate between two human faces. Full-fledged recognition is a higher-order task and remains unproved in the fish.

“To go from discrimination to recognition,” Newport explained to me, “you would have to show different views, or a partial view.”

In other words, the fish would have to know that what it’s looking at isn’t the whole story, and be able to infer what’s missing.

“That’s the next experiment,” she said.

Still, even this level of discrimination should have been beyond the archerfish’s ability.