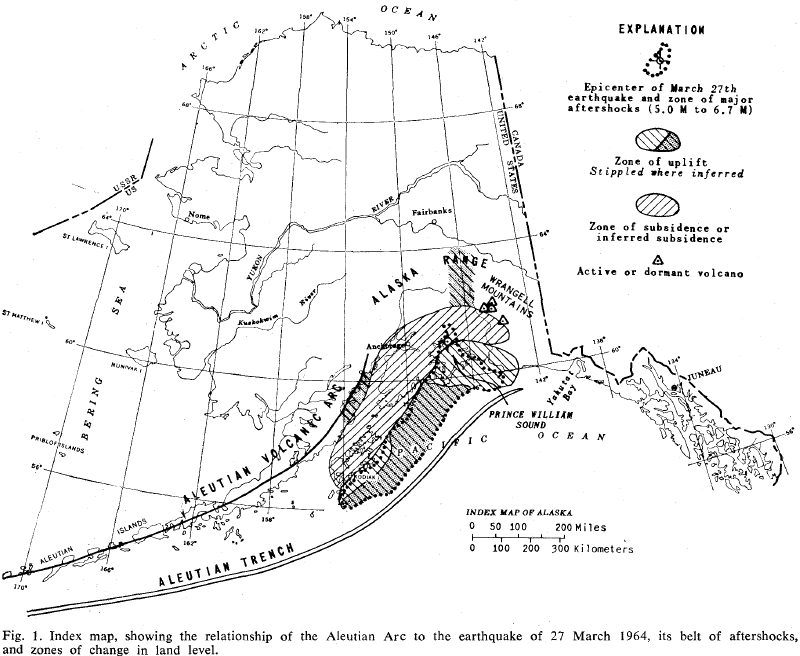

Among many geologists of the boomer generation, the Alaska earthquake of March 27, 1964 is a touchstone of our formative years. Black-and-white images of ruin and upheaval from the then-new state of Alaska burst into our consciousness. News reached us of deadly “tidal waves” washing down the West Coast. But beyond rocking us kids toward geological careers, that earthquake was a key event in the 1960s revolution in earth science.

The quake, a magnitude 9.2, was the largest ever recorded in U.S. history. It lasted more than four minutes. The earthquake and the ensuing tsunami killed an estimated 131 people.

Geologist George Plafker of the U.S. Geological Survey was in Seattle the afternoon of the quake, attending a regional meeting of the Geological Society of America. He didn’t feel anything, but some colleagues had been up in Seattle’s Space Needle and felt the slow rocking typical of great earthquakes at great distances. His agency sent him to the scene immediately, along with fellow USGS geologists Art Grantz and the late Reuben Kachadoorian, and on Easter Sunday they set to work.

These three guys were picked because they knew the territory, not because they were earthquake specialists. The Alaskan Branch of the USGS was headquartered in Menlo Park with the rest of the western regional branch. Being in Seattle gave Plafker a day’s lead time in getting there. But the three scientists were what we would call old-school types, skilled in fieldwork and observation and thinking on their feet. They spent a week in Alaska, riding with emergency responders all over the enormous area of damage, then came home and quickly issued USGS Circular 491 while planning a summer field season of intensive work.

Circular 491 includes lots of photographs of damage, preliminary maps and eyewitness accounts. In the town of Homer, “Mr. Glen Sewell heard and saw a fracture, 12 to 18 inches wide, coming toward him from the southeast. The fracture passed between his legs, through a building, and continued on into Kachemak Bay.” Huge waves threw seafloor boulders 100 feet high onto the shore. The sea itself was damaged, as “vast numbers of red snappers, which normally inhabit waters deeper than 400 feet in Prince William Sound, were found floating on the surface.”