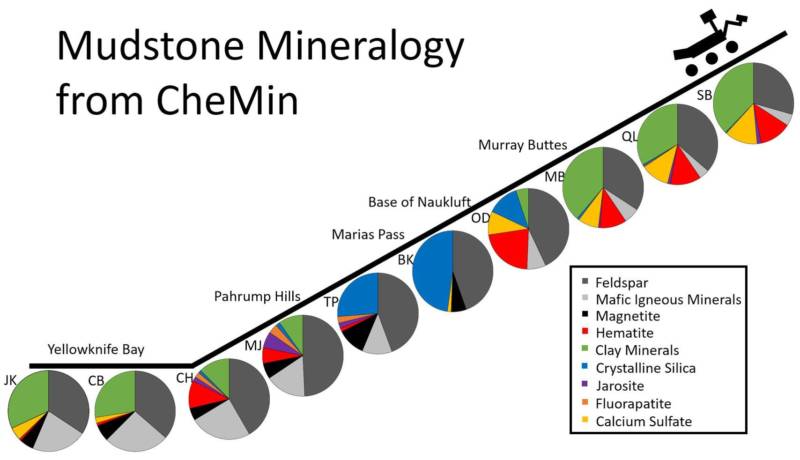

NASA’s Mars Science Laboratory, the rover Curiosity, has dug up a surprise from the rocks of Mars, one that poses a vexing puzzle to scientists. A conspicuous lack of carbonate minerals in the sedimentary rocks of Gale Crater is challenging modern theories for how Mars’ early environment could have been warm enough to support liquid water.

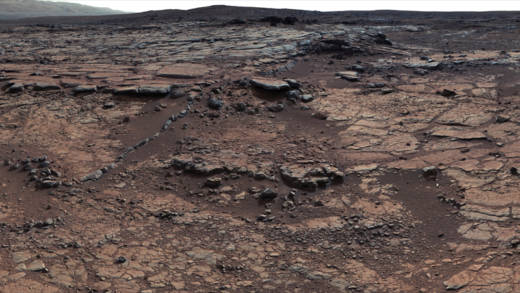

Today, Mars’ atmosphere is too thin for water to exist in a liquid state for long. Atmospheric pressure at Mars’ surface is only a hundredth that of Earth, making Mars a cold, dry desert. Wind-swept landscapes streaked by dust-devils and punctuated by a seasonal global dust storm constitute most of the action to be found on Mars today.

Quest for Water

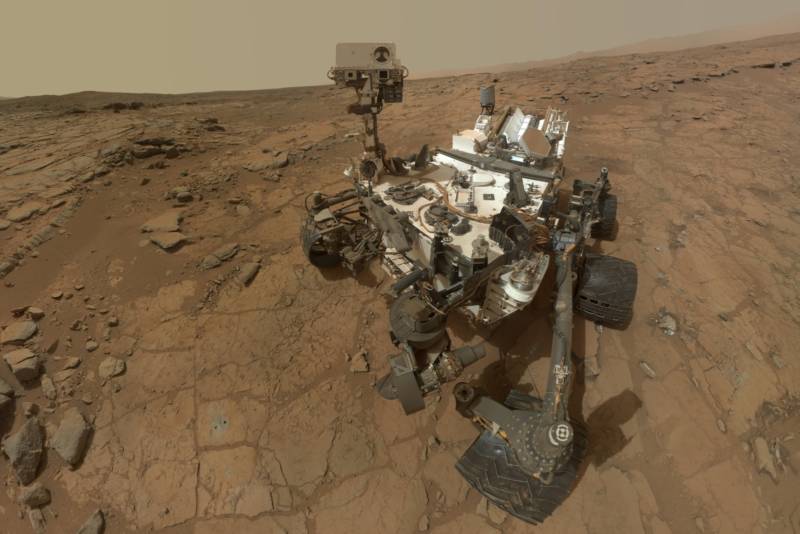

It is in this desolate setting that Curiosity landed in August 2012, lowered to the floor of Gale Crater by a rocket-propelled winch system. Its mission goal was simple: to investigate whether Mars’ environment ever supported liquid surface water, a vital ingredient for the formation of life as we understand it.

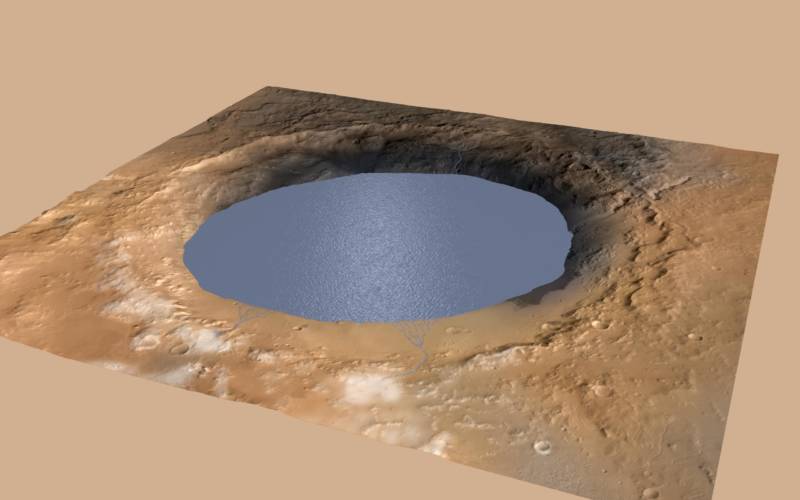

Gale Crater was chosen as a good site for the rover to search for evidence of that warmer, wetter past. Not only was the 96-mile wide impact basin a possible ancient lake bed, but a mountain of sediment at its center—Mount Sharp–presented an accessible index of Mars’ past, its sedimentary layers like the pages of a book spanning billions of years of Mars’ geologic history.

In the nearly 5 years since landing in the bottom-lands of the dry lake bed, Curiosity has driven over 10.1 miles and climbed a vertical distance of about 600 feet. Along the way, it has found ample signs of the existence of the ancient lake, including water-formed minerals, stream beds, dry deltas, and layer upon layer of sediments from the lake’s muddy floor.